Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Institute of Hematology “Seràgnoli,” University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMLBCL) is a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) that has distinct clinical and molecular features. First recognized in the 1980s, PMLBCL was formally established as a distinct subtype of DLBCL in the revised European and American classification of lymphoid neoplasms and, more recently, the World Health Organization classification. It represents 2–3% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases and 6–10% of all DLBCL, and it has a worldwide distribution. PMLBCL occurs more often in young women, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:2 and a median age in the fourth decade.

Clinical Features

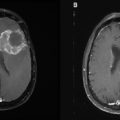

PMLBCL is characterized by a locally invasive anterior mediastinal mass. The mass originates in the thymus and frequently produces compressive symptoms early on, compromising the airway or great vessels, and producing a superior vena cava syndrome. As a result, at the time of diagnosis, 80% of cases have stage I–II disease; in 70% of patients, the mediastinal tumor is larger than 10 cm, often directly infiltrating the lung, chest wall, pleura, and pericardium. Pleural or pericardial effusions are present in one-third of cases. Local invasion results in cough, chest pain, dyspnea, or complaints resulting from caval obstruction. Systemic symptoms, mainly fever or weight loss, are present in less than 20% of cases. Spread to peripheral lymph nodes is infrequent; extranodal sites, however, may be involved, particularly at the time of disease recurrence, with a propensity for involvement of the kidneys, adrenals, liver, ovaries, and central nervous system. Bone marrow infiltration at presentation is rare.

Primary Management

Initial therapy is critical in treating PMLBCL patients. Salvage therapy for recurrence or progressive disease is of limited efficacy; thus, the imperative is to cure at the first attempt when possible. In PMLBCL, there are several controversial topics that warrant further study and they are matters of debate, such as the superiority of third-generation regimens over cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP)-based regimens, the impact of rituximab, the use of involved-field radiotherapy, the assessment of clinical response by PET scan, and the utility of high-dose therapy.

• Front-line therapy: first-generation or third-generation regimens?

An optimum chemotherapy regimen option for patients with PMLBCL has not been clearly established, and the optimal treatment for PMLBCL patients has been a matter of debate. CHOP with or without radiotherapy (RT) is not sufficient, because cure rates do not exceed 50–60%. Some groups have suggested that more aggressive regimens, such as methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin (MACOP-B), may be more effective. Retrospective studies have also suggested a potential benefit of high-dose therapy (HDT) and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), when used as a consolidation of response to first-line chemotherapy.

The approaches of this entity range from first-generation to third-generation chemotherapy regimens. Regarding the use of different chemotherapeutic regimens (CHOP or CHOP-like vs. third-generation regimens), a report by Fisher et al. showed that CHOP and intensive third-generation regimens produce equivalent results. Whereas the CHOP regimen has been used by American investigators, several European centers have suggested that the MACOP-B regimen may be superior to CHOP. However, the debate is still open because it is difficult to compare the advantages of the different types of protocols. On the basis of published phase II data by centers that have used both first-generation chemotherapy regimens like CHOP and other more aggressive third-generation ones like MACOP-B, the results have clearly favored the latter. In two previous studies, we used the MACOP-B regimen in 50 patients (at our center and another Italian center) and in 89 patients (in an Italian multicenter prospective trial), in whom the CR rates were 86% and 88%, respectively, whereas the 5-year relapse-free survival (RFS) rates were 93% and 91%, respectively. In addition, two retrospective studies have reported data regarding the comparison between CHOP and CHOP-like regimens versus MACOP-B and MACOP-B-like regimens as induction chemotherapy in patients with PMLBCL. Our multinational retrospective study compared the outcomes of 426 patients with PMLBCL after first-generation (CHOP or CHOP-like regimens; 105 patients), third-generation [MACOP-B, V(etoposide)ACOP-B; 277 patients], and high-dose chemotherapy schedules (HDT and ASCT; 44 patients). In all these groups, for the most part patients underwent RT after chemotherapy. With chemotherapy, CR rates were 49%, 51%, and 53%, with the first-generation, third-generation, and high-dose chemotherapy strategies, respectively. The final CR rates, after RT on the mediastinum, became 61% for CHOP and CHOP-like regimens, 79% for MACOP-B and etoposide, cytarabine, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin (VACOP-B) regimens, and 75% for high-dose regimens. Projected 10-year OS rates were 44%, 71%, and 77%, respectively; and projected 10-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 35%, 67%, and 78%, respectively. In addition, after RT, 81% of the patients who had already achieved a partial response obtained CR status. Todeschini et al. reported the long-term results from a retrospective multicenter Italian experience in 138 patients with PMLBCL treated with CHOP (43 patients) or MACOP-B or VACOP-B (95 patients). CR was 51% in the CHOP subset and 80% in the MACOP-B and VACOP-B group. The addition of RT on the mediastinum improved the outcome regardless of the type of chemotherapy. These two retrospective studies suggest the superiority of the third-generation chemotherapy strategies over first-generation ones.

A retrospective analysis of 153 patients from British Columbia reviewed outcomes from a geographical region where treatment choice was mandated by era-specific guidelines. Between 1980 and 1992, MACOP-B or VACOP-B was administered, moving to CHOP between 1992 and 2001 and then to rituximab with CHOP (R-CHOP) thereafter. The OS for the cohort was 75% at 5 years, with the OS at 5 years for those treated with MACOP-B or VACOP-B significantly higher at 87% compared with 71% for those patients treated with CHOP (P = 0.048).

• What is the role of rituximab?