Elizabeth A. Ayello and Joy E. Schank

DEFINITION AND INCIDENCE

Persons at end-of-life are at risk for skin injury and ulcerations due to immobility, inadequate nutrition, incontinence, and underlying disease processes. In particular, pressure ulcers, skin tears, and malignant cutaneous wounds (MCWs) create physical and psychoemotional challenges for patients.

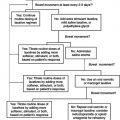

Palliative wound care is an emerging concept. It takes a holistic approach to improving the quality of life and relieving suffering for persons with chronic wounds. Because wound treatment goals and priorities are based on the person’s changing health status, the aims of interventions may shift from wound closure to wound stabilization and prevention of wound deterioration and infection (Ferris, Khateib et al., 2004) (Table 35-1).

| Staging Classification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Stage 1N | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | |

| Wound | |||||

| Closed wound/intact skin | X | ||||

| Closed wound/superficially open to drain then close/hard and fibrous | X | ||||

| Open wound/dermis and epidermis tissue involved | X | ||||

| Open wound/full thickness skin loss involving subcutaneous tissue | X | ||||

| Open wound/invasive to deep anatomic tissues and structures | X | ||||

| Predominant Color | |||||

| Red/pink | X | X | X | ||

| Red/pink/yellow | X | X | |||

| Hydration | |||||

| Dry | X | ||||

| Both moist and dry | X | ||||

| Moist | X | X | X | ||

| Drainage | |||||

| None | X | ||||

| Clear/purulent | X | ||||

| Serosanguineous/bleeding | X | ||||

| Purulent/serosanguineous | X | ||||

| Serosanguineous/bleeding/purulent | X | ||||

| Pain | |||||

| No | X | ||||

| Pain possible | X | X | X | ||

| Yes | X | ||||

| Odor | |||||

| No | X | X | |||

| Yes | X | X | X | ||

| Tunneling/Undermining | |||||

| No | X | X | X | X | |

| Yes | X | ||||

Both pressure ulcers and MCWs can have devastating physical and psychosocial effects. These wounds can be a source of pain, anemia, and infection. These sometimes unsightly and foul-smelling lesions can cause self-concept disturbance, social isolation due to shame or embarrassment, anxiety, fear, and depression (Foltz, 1980; Goodman, Ladd, & Purl, 1993; Miller, 1998; Waller & Caroline, 2000). The family of a patient receiving palliative care at home may not be aware of how to prevent and treat pressure ulcers; therefore, a palliative patient may have to be admitted to the hospital against his or her wishes.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Pressure Ulcers

Pressure ulcers are wounds caused by “unrelieved pressure resulting in damage of underlying tissue” (National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel [NPUAP] et al., 2001). Usually located over bony prominences (e.g., sacrum, heels), pressure ulcers develop when the soft tissue is compressed between a bony prominence and an external surface, disrupting the blood supply and resulting in cellular death. Risk factors for the development of pressure ulcers include immobility, incontinence, inadequate nutrition, friction and shearing forces, and altered level of consciousness (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ] [formerly the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research], 1992), as well as a previous healed pressure ulcer.

The incidence of pressure ulcers in any particular practice setting is somewhat difficult to determine, since study designs vary significantly. For example, some studies include stage I pressure ulcers and some do not, and as a result study outcomes vary greatly. In the acute care setting, the incidence of pressure ulcers ranges from 0.4% to 38%, with increased incidence in higher-risk groups, such as the elderly and persons with paralysis. The incidence of pressure ulcers in the nursing home setting is 2.2% to 23.9%. Beginning data from home care studies provide a range of 0% to 17% (NPUAP, Cuddigan, Ayello et al., 2001).

Malignant Cutaneous Wounds

MCWs are ulcerating skin lesions that develop when malignant cells infiltrate the epithelium (Foltz, 1980). MCWs may occur as single lesions or in groups (Haisfield-Wolfe & Baxendale-Cox, 1999). Approximately 5% to 10% of persons with metastatic malignancies have MCWs, usually during the last 3 to 6 months of life (Crosby, 1998; Foltz, 1980; Thiers, 1986; Waller & Caroline, 2000). The malignant processes associated with the development of cutaneous metastases include breast cancer, malignant melanoma, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer (Crosby, 1998). These wounds are sometimes called fungating tumor wounds, which refers to the tendency of these wounds to both ulcerate and proliferate (Mortimer, 1998).

MCWs may result from primary skin lesions or metastasis from other malignant processes. As mentioned, breast cancer is the most common cause of MCWs; up to 25% of persons with breast cancer experience skin metastasis (Waller & Caroline, 2000). The malignancies associated with the development of MCWs are listed in Box 35-1.

Box 35-1

Butterworth-Heinemann

Butterworth-Heinemann

Primary Skin Malignancies

Untreated basal cell carcinoma

Untreated squamous cell carcinoma

Malignant melanoma

Metastatic Spread from Primary Malignancy

Breast

Head and neck

Lung

Stomach

Kidney

Uterine

Ovarian

Colon

Bladder

Lymphoma

Melanoma

Data from Mortimer, P.S. (1998). Management of skin problems: Medical aspects. In D. Doyle, G.W.C. Hanks, & N. MacDonald (Eds.). Oxford textbook of palliative medicine (2nd ed., pp. 617-627). New York: Oxford University Press; Crosby, D.L. (1998). Treatment and tumor-related skin disorders. In A.M. Berger, R.K. Portenoy, & D.E. Weissman (Eds.). Principles and practice of supportive oncology (pp. 251-264). Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; and Waller, A. & Caroline, N.L. (2000). Handbook of palliative care in cancer. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

The initial appearance of a primary skin malignancy may be a sore that does not heal. Metastatic MCWs may begin as hard dermal or subcutaneous nodules and may be fixed to underlying tissue (Crosby, 1998; Thiers, 1986). These lesions occur most commonly in the vicinity of the primary tumor (Crosby, 1998). However, MCWs are also seen at a secondary site related to metastatic disease (Goodman et al., 1993; Miller, 1998). They may vary in color from flesh-toned to red and are usually asymptomatic at early stages (Crosby, 1998).

Malignancies spread to the cutaneous tissues via direct extension or embolization into the vascular or lymph channels (Goodman et al., 1993; Mortimer, 1998). Eventually these lesions infiltrate the epithelium and supporting lymph and blood vessels, interfering with blood flow and the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the tissues, leading to ulceration (Haisfield-Wolfe & Baxendale-Cox, 1999; Mortimer, 1998). Capillary rupture, necrosis, and infection are common, leading to a purulent, friable, and malodorous ulceration (Foltz, 1980; Mortimer, 1998).

Infections in MCWs may be caused by both anaerobic and aerobic pathogens. Anaerobic organisms proliferate in necrotic tissue. The foul-smelling odor of many of the MCWs is due to the release of malodorous volatile fatty acids as metabolic end-products of anaerobic activity (Mortimer, 1998). These wounds can readily become infected with aerobic organisms and produce yellow to green purulent discharge.

Skin Tears

Skin tears are acute traumatic wounds that occur when the epidermis separates from the dermis (Malone, Rozario, Gavinski et al., 1991). Most skin tears are found on the arms and legs, especially over areas of senile purpura (areas where blood vessels become more purple as an individual ages) (Malone et al., 1991; McGough-Csarny & Kopac, 1998; Payne & Martin, 1990). Skin tears can be very distressing for the patient. This can occur from something as simple as tape used to hold an intravenous line. With age, the subcutaneous tissue decreases and leaves the skin very thin and easy to tear. The main concern is often pain control.

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT

Risk Assessment

Two validated risk assessment tools that are used in the United States to identify persons at risk for the development of pressure ulcers are the Braden Scale (www.bradenscale.com/braden.pdf) and the Norton Scale (AHRQ, 1992). Although the onset of risk score differs, both scales produce risk scores based on known risk factors, such as mobility, mental status, and moisture. The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) (2004) also advises that prevention strategies must be implemented for persons with low scores in any risk assessment subscale. These risk scales are readily available in the published guidelines from the AHRQ as well as the newer pressure ulcer guidelines from the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN) (2003). It is important to reassess risk on admission and at intervals, especially in the palliative care setting, where declining functional status and nutritional impairment are anticipated.

Skin Assessment

Do not confuse a skin assessment with a wound assessment. The CMS has provided clinicians with a minimal standard for skin assessment in the recently revised guidance to surveyors for long-term care facilities, Tag F 314 (CMS, 2004). This includes assessing the skin for temperature, color, moisture, turgor, and integrity. Skin assessment should be done on admission, discharge, and weekly. Skin tears and stage I ulcers may be in places that cannot be seen on quick assessment and can be missed. It is important not only to look at the patient’s skin but also to assess pressure areas related to, for example, the wheelchair, bed, linens, stockings, and so on.

Wound Assessment

When any type of ulceration is present, documentation of the degree of tissue destruction is an important aspect of wound assessment. Pressure ulcers, MCWs, and skin tears each have their own classification systems. The current staging system for pressure ulcers from the NPUAP 2001) is as follows:

▪ Stage I: Observable, pressure-related alteration of intact skin whose indicators as compared to an adjacent or opposite area on the body may include changes in one or more of the following parameters: skin temperature (warmth or coolness), tissue consistency (firm or boggy feel), and sensation (pain, itching). The ulcer appears as a defined area of persistent redness in lightly pigmented skin; in darker skin tones, the ulcer may appear with persistent red, blue, or purple hues.

▪ Stage II: Partial-thickness skin loss involving epidermis and/or dermis. The ulcer is superficial and presents clinically as an abrasion, a blister, or a shallow crater.

▪ Stage III: Full-thickness skin loss involving damage or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that may extend down to, but not through, underlying fascia. The ulcer presents clinically as a deep crater with or without undermining of adjacent tissue.

▪ Stage IV: Full-thickness skin loss with extensive destruction, tissue necrosis, or damage to muscle, bone, or supporting structures (e.g., tendon or joint capsules). Undermining and sinus tracts also may be associated with stage IV pressure ulcers.

Because the depth of tissue destruction cannot be seen in necrotic pressure ulcers, these wounds are categorized as “unstageable” in acute or home care. CMS requires necrotic pressure ulcers to be documented as stage IV in long term care (CMS, 2004).

NPUAP raised the issue of problems with the stage I and II definitions at their 2005 consensus conference (Ankrom, Bennett, Sprigle et al., 2005). At present, NPUAP recommends that a new type of pressure ulcer, deep tissue injury (DTI), does not fit into the current staging system and is working on how best to stage it (Black & NPUAP, 2005). The NPUAP Website (www.npuap.org) provides up-to-date information about DTI.

A special type of pressure ulcer that is seen during the last few weeks of life and signals impending death is called the Kennedy terminal ulcer (Kennedy, 1989). Based on research findings, it is pear shaped with irregular borders; the tissue is red, yellow, or black; onset is sudden; it is usually found on the coccyx or sacrum; and death is imminent (occurring within 2 weeks to several months) (Kennedy, 1989; www.kennedyterminalulcer.com).

Staging of Malignant Cutaneous Wounds

Recognizing that the staging system for pressure ulcers does not necessarily apply to assessment of MCWs, Haisfield-Wolfe and Baxendale-Cox (1999) developed and tested a specific staging system for these lesions, which is presented in Table 35-1. The purpose of this scale is to clarify communication among health care professionals to improve patient care, consultation, and comparison of research results. Haisfield-Wolfe and Baxendale-Cox (1999) used digital photography as an adjunct to observation to assess and record the MCW accurately on initial assessment and follow-up.

Classifying Skin Tears

Skin tears have a separate classification system that has three categories based on the amount of tissue lost. In category I skin tears, there is no loss of the epidermal flap. Category II skin tears have partial loss of the epidermal flap, while in category III there is complete loss of the epidermal skin flap (Payne & Martin, 1990, 1993).

Wound Assessment Variables

Staging or classification of wounds is only one part of wound assessment. Photographic documentation may be helpful in assessing and monitoring all types of ulcerative lesions (Miller, 1998). In addition to the stage of pressure ulcer, CMS (2004) requires the following minimal assessment of the wound:

▪ Location

▪ Size of the wound

Length and width are measured, using established landmarks for measurement.

Depth is noted at the deepest point. This is measured by inserting a sterile applicator into the deepest area, holding or marking the applicator stick at the skin surface level, and measuring from the tip of the stick to the mark.

▪ Exudate

Color and consistency of the drainage are documented. Drainage may be serous, sanguineous, serosanguineous, or purulent.

Amount of drainage is noted. It may be described (1) verbally, as scant, moderate, large, or copious; (2) in terms of the number of soaked dressings; or (3) by weight of the dressings.

▪ Pain

Pain at the site may indicate infection, tissue destruction, or vascular insufficiency. The absence of pain may indicate nerve damage (Hess, 1999).

▪ Color and type of wound bed tissue

Red or pink color generally indicates clean, healthy granulation tissue.

Yellow may be the result of infection-related exudate or necrotic slough.

Black tissue indicates eschar from necrosis.

Some wounds have mixed colors. Clinicians use one of two approaches in documenting the color of mixed wounds: (1) use the least desirable color or (2) estimate the percentage of each color within the wound (Hess, 1999). For clear communication, the palliative care team should adopt one of these two approaches as a standard.

▪ Description of wound edges and surrounding tissue

Color and condition of the skin surrounding the pressure ulcer are noted (Hess, 1999).

Temperature of the intact skin is also noted. Heat is a sign of pressure ulcer formation and can also indicate an underlying infection (Hess, 1999).

Some clinicians go beyond these minimal documentation requirements and include the following additional wound characteristics:

▪ Tunneling, which is tissue destruction under intact skin, is also noted and measured. It is measured by inserting a sterile applicator into tunneled areas, holding or marking the applicator stick at the wound edge, and measuring from the tip of the stick to the mark.

▪ Odor is also noted. Wound odor may be described as pungent, strong, foul, fecal, or musty.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Medical history identifies those persons who have diseases that create skin integrity risks, such as heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, and cancer. Past treatments that may affect skin integrity and wound healing, such as radiation therapy or extensive surgery, are also important aspects of the patient’s history. In addition, the advanced practice nurse (APN) assesses the patient’s activity level, mobility, level of consciousness, nutritional status, and hydration status. Many of these factors are included in the risk assessment tools described.

The routine skin inspection includes observing for any areas of discomfort, redness, edema, or ulceration, paying special attention to bony prominences, heels (Figure 35-1), and elbows. Some patients with cancer can have a dehiscence of their wound. In addition, for persons at risk for MCWs, the skin is inspected for the presence of any new nodules, especially in the same general region as the primary tumor. The presence of incontinence or excessive diaphoresis must also be noted for all patients.

|

| Figure 35-1 |

When an ulcerative lesion is present at initial assessment, a history of the lesion is important, including how long it has been present, previous treatments for the lesion, the effectiveness of these treatments, and the psychosocial effect of the lesion on the patient and family (Miller, 1998).

DIAGNOSTICS

On occasion, wound cultures may be appropriate to determine the exact organism causing an infection, to guide subsequent more-specific interventions. Orders must be written to obtain cultures for both aerobic and anaerobic organisms. It is often appropriate to forgo cultures and treat the likely infection on the basis of the appearance and odor of the exudate as recommended in the Clinical Signs and Symptoms checklist developed to identify infection in chronic wounds (Gardner, Frantz, Troia et al., 2001).

INTERVENTION AND TREATMENT

At a CMS meeting (www.cms.hhs.gov/transmittals/downloads/R4SOM.pdf), it was recommended that the usual care of chronic wounds include the following elements: