Valarie A. Pompey

DEFINITION AND INCIDENCE

Retching, an involuntary attempt to vomit, consists of rhythmic, labored spasmodic movement of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles causing regurgitation into the esophagus (Woodruff, 2004). Retching often follows nausea and precedes vomiting. Descriptors include “dry heaves.”

Vomiting, often confused with nausea, is the forceful contraction of the abdominal muscles (stomach), to cause the expulsion of stomach contents through the mouth (National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN], 2005). Common descriptors include “throwing up.”

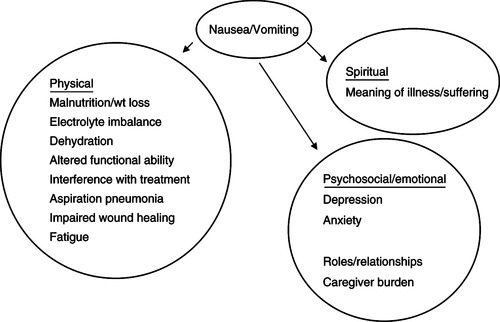

Nausea and vomiting (N/V) are two of the most frequently reported and feared side effects experienced by patients throughout their cancer experience. N/V affects 60% to 80% of cancer patients undergoing active treatment (Cunningham, 2005), 50% to 60% of patients with advanced disease (Herndon, Jackson, & Hallin, 2002), and as many as 40% of terminally ill patients within in their last week of life (Kazanowski, 2001). If untreated, complications can lead to unnecessary hospitalizations and diminished quality of life (Figure 31-1). N/V is particularly prevalent in persons with breast, stomach, and gynecological cancers, as well as persons with AIDS (Kazanowski, 2001). At end-of-life, N/V is commonly seen as a result of certain conditions such as bowel obstruction, hypercalcemia, constipation or impaction, use of opioids, uremia, and increased intracranial pressure secondary to metastatic disease in the brain. Effective management of these individual symptoms during initial and continued therapy profoundly influences symptom response throughout the cancer trajectory (Rhodes & McDaniel, 2001).

|

| Figure 31-1 Data from Woodruff, R. (2004). Nausea and vomiting. In Palliative medicine (4th ed., pp. 223-237). New York: Oxford University Press; and King, C.R. (2001). Nausea and vomiting. In B.R. Ferrell & N. Coyle (Eds.). Palliative nursing (pp. 107-121). New York: Oxford University Press. Oxford University Press |

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

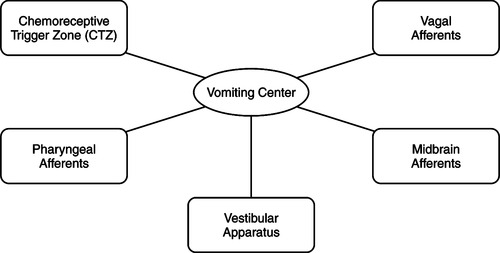

Still not well defined, the physiological mechanisms for N/V are complex and may involve one or more mechanisms and can occur from one or more neurotransmitters (Wickham, 2005). The vomiting center (VC), located in the brainstem along with the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), located in the area postrema of the fourth ventricle of the brain, coordinate the processes involved in N/V. The CTZ is stimulated by chemicals and neurotransmitters found in the cerebrospinal fluid and blood. The CTZ, the VC, and the gastrointestinal tract have many neurotransmitter receptors. Activation of these receptors by noxious stimuli results in the symptoms of N/V. The principal neuroreceptors involved in the emetic response include dopamine and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine 3 [5-HT 3]) receptors. Other receptors involved in signal transmission include acetylcholine, corticosteroid, histamine, cannabinoid, opiate, and neurokinin-1 (NK-1), which are located in the VC and vestibular center of the brain (NCCN, 2005) (Table 31-1).

| Receptors and Neurotransmitters | Trigger | Antiemetic Class |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal Tract | ||

| Serotonin (5-HT 3) | Irritation Gastric stasis Hepatomegaly Radiation therapy Chemotherapy Obstruction | Antihistamine 5-HT 3 antagonist Anticholinergic |

| Vestibular Apparatus | ||

Histamine (H 1) Acetylcholine | Motion | Antihistamine Anticholinergic |

| Chemoreceptor Trigger Zone | ||

Substance P Dopamine (D 2) Serotonin (5-HT 3) | Chemicals Electrolyte imbalance Drugs | NK-1 antagonist Antidopaminergic 5-HT 3 antagonist |

| Cortex | ||

| Pressure receptors | Anxiety, stress Raised intracranial pressure Sights, smells, taste | |

| Vomiting Center | ||

Acetylcholine Histamine receptor (H 1) Serotonin (5-HT 2) | Gastrointestinal tract Vestibular apparatus Cortex Chemoreceptor trigger zone | |

The VC is located in the lateral reticular formation of the medulla oblongata and is situated close to areas in the brain responsible for respiration, salivation, vasomotor processes, and vestibular apparatus (Ezzone, 2000). The VC, which coordinates the process of N/V, receives signals from the cerebral cortex and higher brainstem, thalamus, hypothalamus, and the vestibular system. It also receives emetic impulses via the vagus and splanchnic nerves from the pharynx and gastrointestinal tract when enterochromaffin cells in the upper gastrointestinal tract are stimulated (Figure 31-2). The VC also receives signals from the CTZ, which can initiate vomiting only via the VC (Mannix, 1999).

|

| Figure 31-2 |

Vomiting occurs when efferent impulses are sent from the VC to the salivation center, abdominal muscles, respiratory center, and cranial nerves. Box 31-1 lists common causes of N/V in the palliative care setting; the causes most frequently identified in persons with end-stage disease are identified by an asterisk.

Box 31-1

GASTROINTESTINAL

Gastrointestinal obstruction*

Constipation*

Gastritis*

Gastric stasis*

Squashed stomach syndrome

Gastrointestinal infection

Carcinomatosis

Extensive liver metastasis

PHARYNGEAL IRRITATION

Candida spp. infection

Thick sputum

Cough

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Increased intracranial pressure*

Posterior fossa tumors or bleeding

Meningitis, infectious or neoplastic

MEDICATIONS

Opioids*

Antibiotics

Chemotherapy

Corticosteroids

Digoxin

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Iron

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND EMOTIONAL

Anxiety

Pain

Conditioned response (anticipatory nausea)

SITUATIONAL

Odors

Inadequate mouth care

ASSESSMENT AND MEASUREMENT

Identification of the possible cause(s) of N/V begins with a detailed history and physical examination. In patients with advanced cancer, N/V is frequently due to multiple causes (Woodruff, 2004). Questions about onset, precipitating and aggravating factors, quality (duration, frequency, and severity), and relieving factors should be documented so that an individualized approach to management can be implemented. Assessment of the gastrointestinal status, that is, abdominal distention, presence of bowel sounds, and presence of other associated symptoms such as constipation, should be part of the total process. It is also very important to remember that the most reliable way to assess nausea is through the patient’s report.

Temporal Characteristics

▪ Onset: When did it start?

▪ Pattern: Specific times of the day? Continuous or intermittent?

If it is intermittent, what are the frequency and length of episodes?

Does nausea precede vomiting, or does vomiting come without warning?

▪ Relieving and aggravating factors: What makes it better or worse?

Affected by movement?

Better or worse with eating?

In certain situations?

With certain smells?

Risk Factors

Disease Related

▪ Primary or metastatic tumor of the central nervous system that includes the VC or increased intracranial pressure

▪ Obstruction of a portion of the gastrointestinal tract

▪ Food toxins, infection, or motion sickness

▪ Metabolic abnormalities, such as hyperglycemia, hyponatremia, hypercalcemia, and renal or hepatic dysfunction

▪ Advanced stomach and breast cancers, any cancer at end-stage

▪ Pharyngeal irritation from tenacious sputum, candidiasis

▪ Hepatomegaly

Treatment Related

▪ Stimulation of receptors of the labyrinth of the inner ear

▪ Obstruction, irritation, inflammation, and delayed gastric emptying stimulating the gastrointestinal tract through the vagal visceral afferent pathway

▪ Stimulation of the VC through cellular by-products associated with cancer treatments. Chemotherapy drugs are classified by their potential to cause chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) within the first 24 hours of drug administration. N/V occurring within the first 24 hours of chemotherapy drug administration is called acute. N/V that persists for several hours or days 24 hours or more after treatment is termed delayed. Anticipatory N/V can develop depending on how successful prior experiences at control have been and is usually triggered by cues linked to prior treatments such as smells, sounds, etc.

▪ Stimulation of the VC through afferent pathways from radiation therapy of the gastrointestinal tract. Radiation-induced nausea and vomiting (RINV) depends on the site of treatment, size of treatment field, and radiation dose. Patients at highest risk have received a large volume of radiation to the upper abdominal tissues. Time to onset of radiation is related to the dose fraction: 10 to 15 minutes after total body irradiation or hemibody irradiation to as much as 1 to 2 hours after smaller doses of radiation to a specific site (i.e., upper abdomen). RINV may persist for several hours (Wickham, 2005).

▪ Side effects of medications such as digitalis, morphine, antibiotics, iron, vitamins, and chemotherapy agents. Emetogenicity of various chemotherapy agents is given in Box 31-2.

Box 31-2

Oncology Education Services (OES)

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Oncology Education Services (OES)

CHEMOTHERAPY

Emetic Risk of Chemotherapy (Generic Names)

High (>90%)

Carmustine (>250 mg/m 2)

Cisplatin (>50 mg/m 2)

Cyclophosphamide (>1500 mg/m 2)

Dacarbazine (>500 mg/m 2)

Mechlorethamine

Procarbazine (orally)

Streptozocin

Moderate (30% to 90%)

Aldesleukin (IL-2)

Cyclophosphamide (<1500 mg/m 2)

Carmustine (<250 mg/m 2)

Doxorubicin

Cisplatin (<50 mg/m 2)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree