Case study 29.1 A 31-year-old male rodeo clown has recently been diagnosed with chronic-phase CML. He is intermediate risk by both the Sokal and Hasford classification schemes. He has three siblings. Surprisingly, insurance coverage for rodeo clowns is good (especially for traumatic injuries), so there is not a problem with obtaining either TKI therapy or transplantation. Being a risk taker, he is attracted to transplantation since it is “one and done” rather than a potential lifetime of therapy.

1. All things considered, what do you recommend?

Tyrosine kinase therapy Allogeneic transplantation Clinical trial The question here is whether transplantation should ever be offered as upfront therapy for newly diagnosed chronic-phase CML . In this setting, treatment with any TKI will yield 10-year survival of ∼90. Compare this to the pre-TKI years, where the median survival for this group would be ∼6 years. Allogeneic transplantation for chronic-phase CML would expect to yield ∼85 disease-free survival (with either a matched related or unrelated donor), but it is associated with an upfront risk of morbidity and mortality. Thus, regardless of whether the patient is a risk taker or not, allogeneic transplant should be reserved for those patients who are intolerant or fail multiple TKI agents, or who progress to the accelerated or blast phase. In the past, patients who acquire the T315I mutation were also candidates for transplantation, but the recent approval of ponatinib, which is highly effective against all Abl mutations, now has become the preferred initial approach for these cases.

After discussion, the above patient decides that he will try a TKI after all. He has no other medical history of relevance in considering a choice of imatinib versus nilotinib versus dasatinib. However, from your discussion, it becomes clear that the life of the rodeo clown may come into play in your decision. Besides the considerable “bumps” of the job, the schedule is hectic, with irregular eating, and the lifestyle not altogether monastic.

2. After much consideration, what do you decide on?

Imatinib Dasatinib Nilotinib How do we decide which TKI to use? Three randomized phase III studies have shown that nilotinib and dasatinib have better short-term (12 m) efficacy, measured by cytogenetic response, molecular response, and progression rates, but thus far neither have shown a survival advantage. It is not clear if this is because there will be no survival advantage of the second-generation TKI versus imatinib, or if the survival with any regimen is so good that one would need a huge study, with longer follow-up, to see the effect.

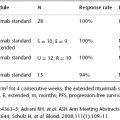

Given that this patient presents with intermediate-risk disease by the Sokal and Hasford scores, many physicians would lean toward starting therapy with the more potent dasatinib or nilotinib, hoping that the more potent inhibition would better prevent progression to advanced-phase disease. However, the second-generation TKIs have more hematopoietic toxicity, especially grades 3–4 thrombocytopenia (e.g., ∼10% grade 3–4 with imatinib versus 20% with dasatinib in the US Intergroup trial). Given this consideration and the patient’s occupational propensity to collide with one-ton hoofed animals, you and the patient decide to start therapy with imatinib (A) (Table 29.1 ).

Table 29.1 et al . N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2251–9; Kantarjian H, et al . N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2260–70; Radich JP, et al . Blood; 2012;120:3898–905).

He starts on 400 mg a day, and while you have advised him to take off work, he has rejoined the rodeo circuit. He returns to your office 3 months later. He has normalized his complete blood count. He refuses to have a bone marrow aspiration for cytogenetics (“My back side is sore enough already, Doc!”). His peripheral blood polymerase chain reaction (PCR) shows a Bcr–Abl of 12% IS (there is no baseline test). When asked if he is taking his medication, he replies “mostly.”

3. After furrowing your brow, what do you decide?

Continue on imatinib Switch to nilotinib or dasatinib Refer to allogeneic transplantation What does early response mean, especially in the context of questionable compliance? A growing body of data suggest that early (3 m) response predicts outcome, and that patients who do not have a BCR–ABL <10% IS at 3 m have an inferior outcome (cytogenetic, molecular, and survival) compared to patients with a better response. This relationship seems to hold for both upfront CML and those patients who switch to a second-generation TKI after poor tolerance or efficacy to imatinib. Thus, some experts would advocate switching to an alternative TKI with such a poor 3 m BCR–ABL PCR result, even though there are not data suggesting that switching in these patients will actually change their natural history. The story is complicated here by the suspicion that the patient is not compliant. Adherence to the prescribed dose schedule of imatinib is surprisingly poor; not surprising is that if one does not take imatinib, it doesn’t work. Thus, adherence to at least 90% of the prescribed imatinib dose is associated with a far superior outcome in reaching treatment milestones. Thus, for this patient, it is reasonable to continue on imatinib, with close follow-up.

He continues on imatinib, and while he says he understands your concern and promises to return in 3 months, he misses his next appointment. After 9 months without contact, you receive a postcard from him from the Calgary Stampede rodeo. It states, “Dear Doc. All is going well. Maybe some bruising lately, but it’s been a tough week in the pen. Some fevers as well. Guess I caught a bug. See you in a week. Wish you were here.” He arrives a week later with a white blood cell count >100k, with 17% peripheral blood myeloblasts, an enlarged spleen, and 10 lbs of weight loss.

4. As he is now in accelerated phase, what do you recommend?

Switch to nilotinib, dasatinib, or ponatinib and watch response Start on second-generation TKI, then move to allogeneic transplant AML induction therapy, then TKI, then transplant What do you do with the rare patients who, from either poor compliance (bad idea) or aggressive disease (bad luck), progress to aggressive CML? While patients who fail TKI and progress to accelerated phase can control their disease and sometimes achieve even a complete cytogenetic remission, their long-term disease survival is poor. Thus, transplantation is their best alternative. If a patient is in accelerated phase, a trial of dasatinib or ponatinib (nilotinib is not approved for advanced-phase disease) is warranted while the patient is securing a donor. Hopefully, by this time he and his siblings have been typed (you did think to do that, right?).