Case study 27.1

A 54-year-old man with no significant medical history reports a 3-month history of mild fatigue during his annual routine checkup with his internist. The physical examination is unremarkable. A complete blood count (CBC) reveals a white blood cell (WBC) count of 9.6 × 109/L, with the manual differential revealing 45% neutrophils, 20% lymphocytes, 5% monocytes, and 25% eosinophils (absolute eosinophil count: 2.5 × 109/L). The hemoglobin and platelet count are normal.

1. Should the patient be referred to a hematologist for a bone marrow biopsy?

- Yes

- No

A systematic approach to the differential diagnosis of eosinophilia should be undertaken before assuming a bone marrow biopsy is immediately necessary to make a diagnosis in this case. The starting point is to recognize the cutoff for a normal eosinophil count. The upper limit of normal for the range of percentage of eosinophils in the peripheral blood is generally 3–5%, with a corresponding absolute eosinophil count (AEC) of 0.35–0.5 × 109/L. The severity of eosinophilia has been arbitrarily partitioned into mild (AEC from the upper limit of normal to 1.5 × 109/L), moderate (AEC: 1.5–5.0 × 109/L), and severe (AEC: >5 × 109/L). In 2011, the Working Conference on Eosinophil Disorders and Syndromes proposed the term “hypereosinophilia (HE)” for persistent and marked eosinophilia (1.5 × 109/L).

The first step in the work-up of eosinophilia is to rule out reactive (secondary) causes. This requires a thorough history and physical examination to evaluate patient travel and exposures, new medications, and a review of prior blood counts to evaluate the temporality and severity of eosinophilia. In developing countries, eosinophilia most commonly derives from infections, particularly tissue-invasive parasites. In developed countries, allergy/atopy conditions, hypersensitivity conditions, and drug reactions are the most common causes of eosinophilia. Other secondary causes of eosinophilia to consider include collagen-vascular diseases (e.g., Churg-Strauss syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus), pulmonary eosinophilic diseases (e.g., idiopathic acute or chronic eosinophilia pneumonia, tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, etc.), allergic gastroenteritis (with associated peripheral eosinophilia), and metabolic conditions such as adrenal insufficiency. Malignancies may be associated with secondary eosinophilia, which usually results from elaboration of eosinophilopoietic cytokines such as IL3, IL5, and GM-CSF from the tumor. Such cytokine-driven eosinophilia has been associated with various solid malignancies, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Routine testing for secondary causes of eosinophilia typically involves ova and parasite testing, and sometimes stool culture and antibody testing for specific parasites (e.g., strongyloides and other helminth infections). The type and frequency of laboratory and imaging tests (e.g., chest X-ray, electrocardiogram and echocardiography, or computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis) are guided by the patient’s travel history, symptoms, and findings on physical examination. For patients with eosinophilia and signs or symptoms referable to lung disease, pulmonary function testing, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage or biopsy, and serologic tests (e.g., aspergillus immunoglobulin E (IgE) to evaluate for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA)) may be considered.

The internist finds no reactive causes for eosinophilia. Although a referral is placed to hematology, the patient does not follow up with this consultation. The patient returns 6 months later complaining of increasing shortness of breath with exertion. On physical examination, an S3 murmur is auscultated, the spleen is palpated 5 cm below the left costal margin, and 2+ lower extremity edema is present. The current CBC reveals a WBC count of 23 × 109/L with 32% eosinophils (absolute eosinophil count: ∼7.4 × 109/L). Myeloid immaturity is not present. An echocardiogram reveals a decreased ejection fraction (EF) of 45%. Endomyocardial biopsy reveals an extensive eosinophilic infiltrate. No new reactive causes of eosinophilia have emerged.

2. Does the patient meet the criteria for idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES)?

- Yes

- No

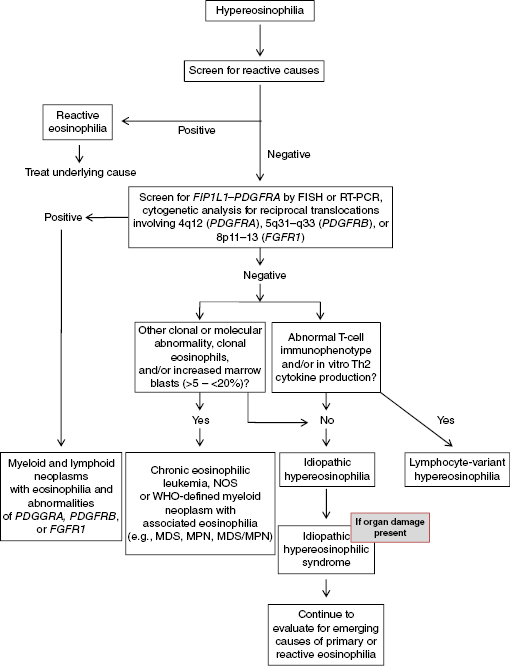

Idiopathic HES is a diagnosis of exclusion whose criteria include an absolute eosinophil count >1.5 × 109/L lasting for more than 6 months, signs of organ damage, and other causes of eosinophilia have been ruled out. Although no obvious causes of reactive eosinophilia have emerged, a work-up for primary (clonal) eosinophilia has not yet been undertaken (Figure 27.1).

Figure 27.1 Diagnostic algorithm for evaluation of hypereosinophilia. FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; NOS, not otherwise specified; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; WHO, World Health Organization.

Figure 27.1 Diagnostic algorithm for evaluation of hypereosinophilia. FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; NOS, not otherwise specified; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; WHO, World Health Organization.

The current World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms provides guidance for approaching the evaluation of primary eosinophilias. In the current edition, a new major category was added, “Myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and abnormalities of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRB), or fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1)” (Tables 27.1 and 27.2). “Chronic eosinophilic leukemia—not otherwise specified” (CEL-NOS) is another bone marrow–derived eosinophilic neoplasm, one of eight diseases within the World Health Organization (WHO) category of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) (Tables 27.1 and 27.2). CEL-NOS is defined by the absence of the Philadelphia chromosome or a rearrangement involving PDGFRA/B or FGFR1. It also excludes other WHO-defined acute and chronic myeloid neoplasms that may be associated with eosinophilia. CEL-NOS is characterized by an increase in blasts in the bone marrow or blood (but fewer than 20% to exclude acute leukemia as a diagnosis), and/or there is evidence for a nonspecific cytogenetic abnormality (e.g., trisomy 8) or other clonal marker (Table 27.2). If none of these entities are identified (including lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilia; discussed further in this chapter), then the diagnosis of idiopathic hypereosinophilia (organ damage absent) or idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (organ damage present) can be made (Table 27.2).

Table 27.1 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid malignancies (Source: Swerdlow S, et al., editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008).

- Acute myeloid leukemia and related disorders

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN)

- Chronic myelogenous leukemia, BCR-ABL1 positive

- Chronic neutrophilic leukemia

- Polycythemia vera

- Primary myelofibrosis

- Essential thrombocythemia

- Chronic eosinophilic leukemia, not otherwise specified

- Mastocytosis

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms, unclassifiable

- Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)

- Refractory cytopenia with unilineage dysplasia

- Refractory anemia

- Refractory neutropenia

- Refractory thrombocytopenia

- Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts

- Refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia

- Refractory anemia with excess blasts (RAEB)

- Myelodysplastic syndrome with isolated del(5q)

- Myelodysplastic syndrome, unclassifiable

- MDS/MPN

- Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia

- Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia, BCR-ABL1 negative

- Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia

- MDS/MPN, unclassifiable

- Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis (RARS-T) (provisional entity)

- Myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms associated with eosinophilia and abnormalities of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1

- Myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms associated with PDGFRA rearrangement

- Myeloid neoplasms associated with PDGFRB rearrangement

- Myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms associated with FGFR1 abnormalities

|

Table 27.2 2008 World Health Organization classification of eosinophilic disorders (Source: Swerdlow S, et al., editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008).

Myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and abnormalities of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1 |

|---|

Diagnostic criteria of an MPN1 with eosinophilia associated with FIP1L1–PDGFRA

A myeloproliferative neoplasm with prominent eosinophilia

and

Presence of a FIP1L1–PDGFRA fusion gene2

Diagnostic criteria of MPN associated with the ETV6–PDGFRB fusion gene or other rearrangement of PDGFRB

A myeloproliferative neoplasm, often with prominent eosinophilia and sometimes with neutrophilia or monocytosis

and

Presence of t(5;12)(q31∼q33;p12) or a variant translocation3 or demonstration of an ETV6-PDGFRB fusion gene or rearrangement of PDGFRB

Diagnostic criteria of MPN or acute leukemia associated with an FGFR1 rearrangement

A myeloproliferative neoplasm with prominent eosinophilia and sometimes with neutrophilia or monocytosis

or

Acute myeloid leukemia or precursor T-cell or precursor B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoma (usually associated with peripheral blood or bone marrow eosinophilia)

and

Presence of t(8;13)(p11;q12) or a variant translocation leading to FGFR1 rearrangement demonstrated in myeloid cells, lymphoblasts, or both |

Chronic eosinophilic leukemia, not otherwise specified (NOS)

- There is eosinophilia (eosinophil count >1.5 × 109/L).

- There is no Ph chromosome, BCR–ABL fusion gene, other myeloproliferative neoplasms (PV, ET, PMF, or systemic mastocytosis), or MDS/MPN (CMML or atypical CML).

- There is no t(5;12)(q31∼q35;p13) or other rearrangement of PDGFRB.

- There is no FIP1L1–PDGFRA fusion gene or other rearrangement of PDGFRA.

- There is no rearrangement of FGFR1.

- The blast cell count in the peripheral blood and bone marrow is less than 20%, and there is no inv(16)(p13q22) or t(16;16)(p13;q22) or other feature diagnostic of AML.

- There is a clonal cytogenetic or molecular genetic abnormality, or blast cells are more than 2% in the peripheral blood or more than 5% in the bone marrow.

|

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES)

Exclusion of the following:

- Reactive eosinophilia

- Lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilia (cytokine-producing, immunophenotypically aberrant T-cell population)

- Chronic eosinophilic leukemia, not otherwise specified

- WHO-defined myeloid malignancies associated eosinophilia (e.g., MDS, MPNs, MDS/MPNs, or AML)

- Eosinophilia-associated MPNs or AML/ALL with rearrangements of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1

- The absolute eosinophil count of >1500/mm3 must persist for at least 6 months, and tissue damage must be present. If there is no tissue damage, idiopathic hypereosinophilia is the preferred diagnosis.

|

A time window of sustained eosinophilia for 6 or more months is no longer universally accepted as necessary criterion for HES. In part, this relates to the fact that modern evaluation of eosinophilia can usually proceed rapidly, and some patients may require immediate treatment. It is difficult to predict what duration and severity of eosinophilia will precipitate tissue damage in individual patients. HES is considered a provisional entity that may change to a specific diagnosis if a defined basis for eosinophilia emerges over time.

3. Which of the following genetic markers should be obtained from the peripheral blood as part of the initial work-up of primary eosinophilia in this patient?

< div class='tao-gold-member'>