Blast Crisis of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

1. How common is blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)?

Blast crisis of CML is commonly referred to as the “terminal phase” of CML—not, hopefully, due to its morbidity but given that it represents the final phase of a disease in which the majority of patients are diagnosed in a chronic phase and treatment is aimed at prevention of a penultimate accelerated phase or blast crisis. This principle begets the most obvious answer to this question: prevention and better therapies have diminished it tremendously! Although the prevalence of CML is increasing given the effectiveness of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), the number of cases of transformation to blast crisis has fallen and management of blast crisis has changed accordingly; it still represents a frontier where advances are needed. Prior to the availability of current therapy options, transformation rates were as high as 20% of CML cases; this has fallen to ∼1%. The rare patient who presents with de novo blast phase disease (not arising from chronic-phase CML) can be treated with lineage-specific regimens that nearly always incorporate TKI therapy; the patient who, despite good initial therapy in the chronic or accelerated phase with TKI therapy, progresses to blast crisis likely has a more complex dominant mechanism of resistance, and careful selection of therapy is warranted.

In clinical trials of chronic-phase CML treated with TKIs, including evolved (second-generation) TKIs, we still observe, albeit rarely, transformation to the blast phase even in the face of early response. Although early and efficient disease burden reduction has proven to be the key toward limiting progression to blast crisis, in some cases the likely unstable clones responsible for transformation preempt TKI therapy and relatively quickly exploit their growth advantage and appear.

Last, as global healthcare evolves and access is gained increasingly to diagnostics as well as to specific therapies such as TKIs for Philadelphia chromosome–positive (Ph+) leukemia, it is noted that the presentation of CML is possibly skewed more toward the accelerated and blast phase in countries such as India, as well as typical presentation as much as a decade younger than in other parts of the world. The causes of such differences remain to be elucidated.

2. What is the nature of blast phase CML?

The most prevalent phenotype of blast phase CML is indeed that evolved from chronic- or accelerated-phase CML, which is resistant to therapy and manifests as a clonal disease bearing ABL kinase domain mutations 50% or more of the time. De novo blast crisis still occurs and, as mentioned, may represent untreated chronic CML with rapid progression prior to the patient seeking medical attention, especially in developing countries. Common in accelerated phase and blast crisis are (i) a higher frequency of Abl kinase domain mutations and (ii) a spectrum of mutations skewed toward an increasing amount of cases with T315I and the so-called p-loop (phosphorylation loop, most commonly at positions 250, 252, 253, and 255) mutations.

In addition to kinase domain mutations, recent analyses have continued to show that clonal evolution—chromosome anomalies aside from the Ph chromosome in the CML clones, particularly via “major route” pathways [trisomy 8, an additional Ph chromosome, isochromosome 17 (17q), and trisomy 19]—is commonly observed in the setting of transformation to blast crisis. Additional findings include p53 mutations, recently characterized mutations such as ASXL1 and TET2, as well as altered gene expression profiles with altered regulation of select sets of genes, which are potentially targetable for therapy at some point.

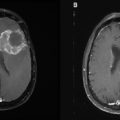

Clinically, the features of blast phase CML are akin to those of acute leukemia; first and foremost, the main delineator of stage, the blast cell count in the marrow or blood, registers at 20% or greater by newer definitions or 30% or greater by traditional definitions. Significant thrombocytopenia and progressive anemia are common objective findings; fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, bone pain, and abdominal symptoms from splenic enlargement are common subjective complaints. Bleeding is increased in the setting of thrombocytopenia, and complications from high leukocyte count—leukostasis and tumor lysis syndrome—are more frequent.

When CML terminates in blast phase, it is curious to many that it takes shape as either a lymphoid or myeloid phenotype; historically, it is twice as likely to develop as a myeloid transformation than a lymphoid type, and the ability to de-differentiate to either type, or a mixed type, speaks to the early stem cell origin of CML.

3. What are the best therapy options for blast crisis of CML?