2 Children’s Hospital, University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany

Introduction

For clinicians managing patients with lysosomal storage disease (LSD), the early years of the 21st century have been characterized by the introduction of a number of new, disease specific, therapies. Initial results from the use of these treatments all suggest that the best results are obtained in patients that present early in the course of the disease before the development of irreversible organ damage. As a consequence, clinicians are under increasing pressure to make a timely diagnosis to allow their patients to benefit from these advances. In the absence of newborn screening for LSD early diagnosis has to depend on clinical acumen and as the disorders are remarkably variable this may involve a number of different specialists.

In some patients the presentation may be in the newborn period with hydrops foetalis, whereas in others, with the same enzyme deficiency (but a different genetic mutation), onset may be in late adulthood.

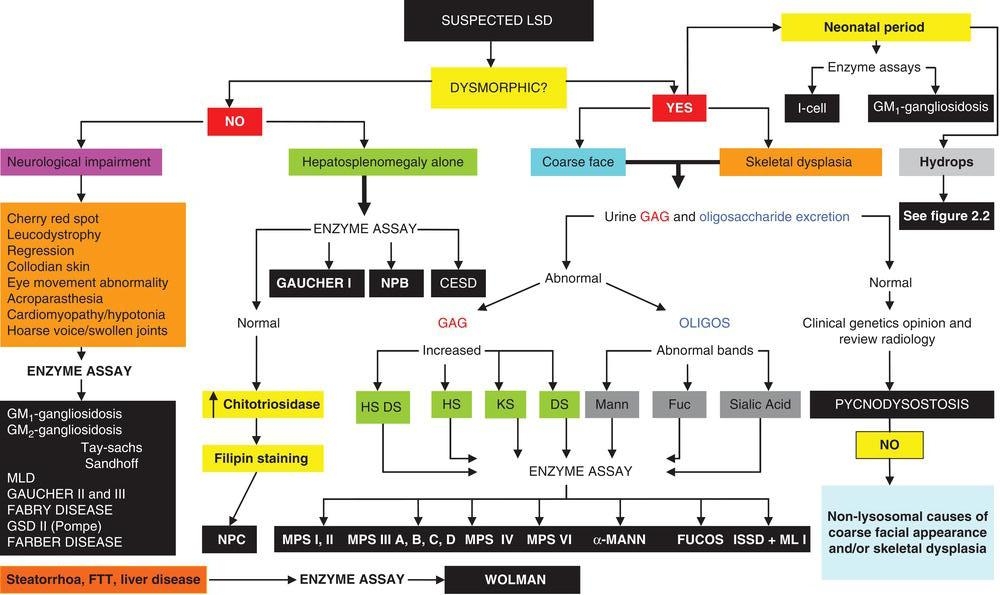

For many patients the onset of symptoms may be in the first months or years of life following an unremarkable early course. The first signs may be a slowing of development and other neurological abnormalities; in other patients, visceromegaly or coarse features may be present. Recognition of these clinical signs will assist in the choice of the most appropriate diagnostic tests (Figure 2.1). Increasingly LSDs are being diagnosed for the first time in adult life. In this group, presentation may be atypical and neuropsychiatric manifestations in the absence of dysmorphic features or visceromegaly are much more common in these patients.

Clinical presentation

Hydrops foetalis

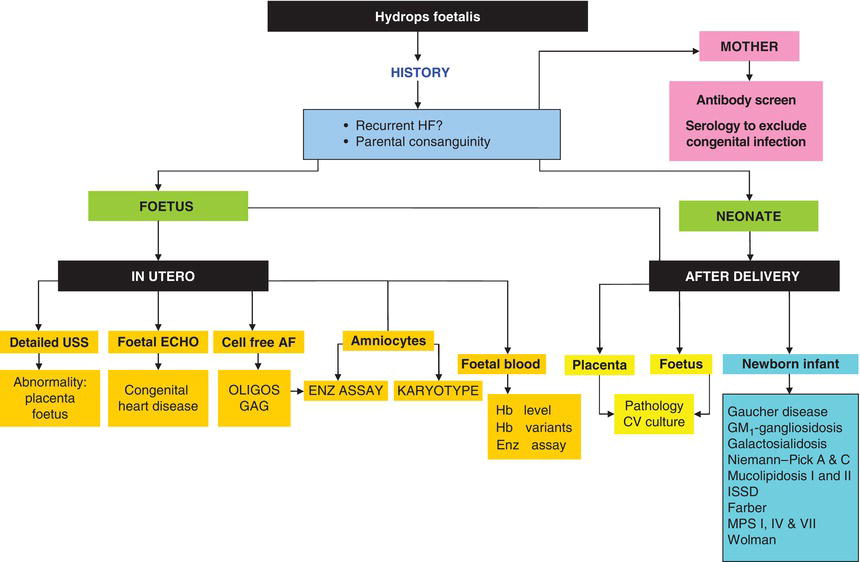

Hydrops foetalis (HF) can be caused by a wide range of foetal, placental or maternal disorders. Foetal mortality is high and so every effort must be made to recognize those disorders that may be associated with an increased risk of recurrent hydrops. This area of prenatal presentation has been extensively reviewed [1]. Figure 2.2 illustrates a suggested diagnostic approach when presented with a hydropic pregnancy. Placental pathology is often very useful as the placenta may appear pale and bulky to gross examination, and lysosomal vacuolation is usually readily seen by light or electron microscopy in cases where the HF is secondary to LSD.

Dysmorphism

The facial appearance of patients with underlying LSDs associated with dysmorphism (Figure 2.1) is often labelled as “coarse” and is seen in its fully developed form in Mucolipidosis II (ML II, I-cell disease) when it may be noticed at birth (Figure 2.3). In most other disorders appearance is normal at birth and the facial phenotype that develops over the first year of life is characterized by a flattened, wide nasal bridge, frontal bossing, thickened gums and macroglossia. Infants affected by some LSDs (in particular, mucopolysaccharidoses) may be large at birth and growth may be normal for the first 2 or 3 years, but then slows. There is a characteristic skeletal dysplasia (dysostosis multiplex, described in more detail later), joint contractures and often both umbilical and inguinal hernias.

Figure 2.1 Lysosomal storage disease: an approach to clinical diagnosis. CESD – cholesterol ester storage disease, DS – dermatan sulfate, Fuc – fucosidosis, GAG – glycosaminoglycans, GSD – glycogen storage disease, HS – heparan sulfate, ISSSD – infantile sialic acid storage disease, KS – keratan sulfate, Mann – mannosidosis, ML – mucolipidosis, MLD – metachromatic leucodystrophy, MPS – mucopolysaccharidosis, OLIGOS – oligosaccharides, NPB – Niemann–Pick disease type B, NPC – Niemann–Pick disease type C.

Figure 2.2 Hydrops foetalis: an approach to diagnosis. AF – amniotic fluid, CV – chorionic villus, ECHO – echocardiogram, ENZ – enzyme assay, GAG – glycosaminoglycan analysis, Hb – haemoglobin, HF – hydrops foetalis, ISSD – infantile sialic acid storage disease, OLIGOS – oligosaccharide analysis, USS – ultrasound scan.

Figure 2.3 Infant with Mucolipidosis II (I-cell disease) day 1. Facial features of LSD already apparent.

Patients with acute neuronopathic Gaucher disease (GDII) can present with severe icthyosis (“collodian baby”), unusual facies, arthrogryposis, enlargement of the liver and spleen, and hernias. Another dermatological clue to the presence of underlying LSD is the abundant Mongolian blue spots seen in children with mucopolysaccharidoses.

Upper airway obstruction, deafness and frequent respiratory infections

Many infants with underlying LSD fail their neonatal hearing assessment. In those that go on to develop the characteristic facial dysmorphism, upper airway obstruction with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and associated frequent upper respiratory infections are common. These patients may present to Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) surgeons in the first year of life before underlying LSD has been considered, and infants that require ENT surgery in the first 12–18 months of life should be viewed as potential LSD patients and investigated appropriately [2]. In Mannosidosis deafness is a very early symptom and is observed in virtually all affected individuals.

Cardiac disease

In infantile Pompe disease (glycogen storage disease type II, acid maltase deficiency), cardiac failure, cardiac arrhythmia and cardiomegaly may all be present at birth. Indeed in a number of affected infants, cardiomegaly has been demonstrated on foetal ultrasounds performed in the last trimester of pregnancy. Affected infants also have macroglossia with a protruding tongue and are generally hypotonic. In addition to the cardiomyopathy demonstrated on echocardiography (usually hypertrophic, occasionally dilated) there is also elevation of liver enzymes and CPK on biochemical testing and the blood film will reveal vacuolated lymphocytes in the vast majority of affected patients.

Neonatal cardiomyopathy is a feature of other LSDs and is seen commonly in GM1-gangliosidosis, ML II (I-cell disease) and MPS IH (Hurler syndrome). In this group of patients coronary artery disease may also be present and episodes of ischaemia may go undetected unless specifically looked for by electro- and echocardiography [3].

In older patients with LSD, valve involvement (especially mitral and aortic) becomes common and in some older patients valve replacement surgery becomes necessary.

Specific cardiac involvement is a feature of other LSDs (for example, Fabry disease) and this is considered in more detail within the specific disease sections.

Hepatosplenomegaly and liver disease

Hepatosplenomegaly in the newborn period has very many different causes, and the common ones such as bacterial and viral infections or anatomical abnormalities need to be diagnosed quickly as specific treatment may be available.

A number of LSDs can also present with enlargement of the liver and spleen, and in a number of affected patients ascites will also be present. Careful clinical and radiological examination for other abnormalities may be helpful, and in some circumstances bone marrow or liver biopsy may suggest underlying LSD.

In contrast to this non-specific presentation, some infants with Niemann–Pick disease type C (NP-C) have a very typical clinical presentation with liver disease in the newborn period. In these affected infants (about a quarter of all patients with NP-C seen in our clinic) severe liver dysfunction often associated with conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia suggests a diagnosis of biliary atresia and a number of NP-C infants have had surgical procedures to exclude this diagnosis. A significant number of these patients will go on to develop liver failure and die (about one-third) while others will slowly improve over months (and even years in some patients) and eventually make a full recovery from their liver disease only to present with the neurological manifestations of the disease often many years later.

Finally, in the newborn period, patients with early-onset lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL deficiency, Wolman disease) present with severe failure to thrive due to fat malabsorption, liver disease (ultimately progressing to liver failure) and severe anaemia. Calcification of the adrenal glands visible on plain abdominal radiology is an important clue to the diagnosis.

Hepatosplenomegaly in older patients may be the presenting manifestation of Gaucher disease (types I and III), cholesterol ester storage disease and Niemann–Pick disease. There are often abnormal blood lipids as well as haematological abnormalities secondary to hypersplenism and bone marrow infiltration. Respiratory infiltration is often under-recognized in these patients who, on rare occasions, will present with respiratory failure.

Dysostosis multiplex

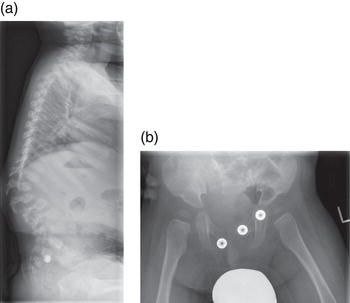

The radiological abnormalities associated with LSD are known as dysostosis multiplex and comprise a characteristic constellation of radiological abnormalities which are seen in the most fully developed form in patients with mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS). Typically the skull is scaphiocephalic and large. The odontoid process of C2 is often dysplastic and the lower vertebrae show anterior beaking, most commonly seen at the thoracolumbar junction and responsible for the gibbus abnormality that is often an early clinical clue to diagnosis [4]. The iliac bones are flared, with a flattened acetabulum and the long bones are short and broad. There is anterior expansion of the clavicles and ribs and the metacarpals are pointed proximally. Some of these general changes are illustrated in Figure 2.4(a) and (b) and have been recently reviewed in some detail [5].

In some disorders the radiological abnormalities are more specific. In MPS IV, for example, the odontoid is often very dysplastic and the vertebrae reveal generalized platyspondyly, with the anterior beaking characteristic of other MPS disorders not as noticeable. In ML II (I Cell disease) there are often intrauterine fractures and in some patients a very severe neonatal skeletal dysplasia is found in conjunction with biochemical evidence of hyperparathyroidism.

Bone disease is a late feature of other LSDs but can occasionally be the first sign of an underlying disorder such as Gaucher disease, where presentation with avascular necrosis or pathological fracture has been reported.

Figure 2.4 (a) Patient aged 18 months with MPS I (Hurlersyndrome) gibbus deformity at thoracolumbar junction with anterior beaking of lumbar vertebrae. (b) Patient aged 12 months with MPS I (Hurler syndrome) acetabular dysplasia and coxa valga.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree