Case study 138.1

A 52-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer has been working with her oncologist for one year. She is currently receiving ixabepilone. She is also on gabapentin to control neuropathy and lorazepam for nausea. She finally reveals to her medical oncologist that she has been taking green tea, turmeric, protocel, and alkaline water for 3 months as recommended by her sister who researched them online. She explains that she feels much better since taking them and has more energy. The medical oncologist advises the patient to stop all supplements as he is concerned about interactions. The patient feels very strongly about continuing.

1. What is the role, if any, for naturopathic medicine in oncology?

- There is no role for natural therapies in mainstream oncology care

- There is a limited role for therapies like yoga and mind–body medicine, but the data are lacking for most other natural therapies

- Integrative medicine, combining conventional medicine with complementary therapies for which there is evidence of safety and effectiveness, provides a role for naturopathic medicine in oncology

There are many misconceptions about the use of naturopathic medicine in oncology care. The most common misunderstanding is how naturopathic doctors approach the management of oncology patients. Naturopathic doctors evaluate oncology patients using criteria very similar to those used by medical oncologists. The management of the patient relies heavily on their diagnosis, performance status, and oncology treatment plan, as well as on other medical comorbidities. Naturopathic doctors also focus on the patient’s current use of natural therapies and evaluate those therapies based on safety, level of evidence, appropriateness, potential for drug interactions, and dosing. Naturopathic doctors spend time educating patients and their caregivers on the safe and appropriate use of evidence-based natural therapies. Prior to providing recommendations, naturopathic doctors critically think through the oncology treatment plan, anticipating short- and long-term side effects, in order to recommend specific interventions with data supporting their use. The recommendations for naturopathic side effect management are made within the context of predicting known or even theoretical herb–drug–nutrient interactions, so that any naturopathic intervention is carefully evaluated to ensure both safety and lack of impact on treatment effectiveness. In addition, naturopathic doctors function as a resource to patients and their caregivers in answering questions and teaching them to think critically about complementary and alternative therapies in their cancer care. In the case of this breast cancer patient, the naturopathic doctor involved with the care of the patient would advise against protocel, as there are no data for its use and the risk for adverse effects or interactions is unknown, and would also educate the patient on basic human physiology and acid–base balance in regard to her attempt to “make her body more alkaline” with alkaline water. In regards to the green tea and turmeric, the naturopathic doctor would evaluate the patient’s medications and oncology treatment plan, and advise as to whether these supplements are appropriate to take, what the risk might be for interactions, and, if indicated, at what doses they should be taken.

To address the green tea consumption in this case, you would first need to determine if there are herb–drug interactions and then determine whether green tea is indicated in advanced-stage breast cancer.

There are several studies worthy of discussion that looked at green tea and its pharmacokinetics. Ixabepilone, whose primary route of metabolism is oxidation via the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzyme CYP3A4, may have negative interactions with green tea. In 2009, an in vitro study showed that various brands of green tea inhibited 3A4 from 5.6% to 89.9%. This variability could be due to variations in growing conditions, harvesting, extraction methods, or whether the tea was decaffeinated or caffeinated. Second, there is an in vivo study with mice showing increased teratogenesis when green tea was combined with cyclophosphamide by increasing CYP2B and inhibiting CYP3A4.

However, an in vivo human study in 2006 of 42 healthy volunteers who were given a decaffeinated green tea supplement with 800 mg epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) for 4 weeks prior to a series of probe drugs were found to have only a small reduction in CYP3A4 activity, resulting in a 20% increase in the area under the plasma buspirone concentration. This study of 42 healthy volunteers is not adequate enough to ensure that the inhibition seen would not interfere with the metabolism of ixabepilone, especially given the in vitro study showing large variations in inhibition with different green tea supplements.

Just as important, however, is the second consideration of whether the addition of green tea would provide benefit in advanced-stage breast cancer, and the data to date does not support its use in this clinical setting. Two studies that were conducted in Japan looked at the correlation of green tea intake with disease recurrence. Both studies indicated benefit in decreased recurrence for those diagnosed with stage I and II breast cancer but no benefit with later-stage disease. These larger studies on green tea and breast cancer have looked at recurrence rates and green tea consumption and have not looked at the use of green tea with late-stage breast cancer. However, given the lack of benefit in recurrence rates for stage III and IV disease, you would anticipate limited benefit, if any, in the case being discussed here. Therefore, in this patient, there is potential for harm with the consumption of green tea supplements and no evidence to indicate benefit.

Based on the above studies combined with the in vitro and in vivo data, there may be a role for green tea in preventing the recurrence of early-stage breast cancer. Research on green tea indicates many areas for potential benefit. The most researched compound in green tea is epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), and it has been shown to be a powerful antioxidant and to inhibit a number of tumor cell proliferation and survival pathways, including inhibition of metaloproteonases, various protein kinases, and tumor proteasomal activity. It has also been shown to regulate DNA replication and transformation.

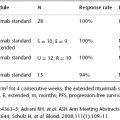

Another important application of the use of green tea may be with the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). A phase I trial of daily oral polyphenon E with a standardized dose of EGCG was given to patients with asymptomatic RAI stage 0–II lymphocytic leukemia. The results were that one patient experienced a US National Cancer Institute Working Group (NCI WG) partial remission, 33% of patients had a ≥20% reduction in absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), and 92% of patients with palpable adenopathy experienced at least a 50% reduction in the sum of the products of all nodal areas during treatment. This is a small study of 33 patients; however, the results are very promising, and a follow-up phase II study showed similar results. When an oral dose of 2000 mg was administered two times daily to patients with CLL, 69% met the criteria for a biologic response with either a sustained decline ≥20% in the ALC, and/or a reduction ≤30% in the sum of the products of all lymph node areas at some point during the 6 months of active treatment.

2. Is there any role for curcumin in her treatment plan?

< div class='tao-gold-member'>