Bone-Related Issues in Oncology

1Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, PA, USA

2Amgen Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA

Introduction

Skeletal integrity is frequently compromised throughout the course of cancer and its treatment. With improvements in effective therapies and recurrence-free survival, patients are living longer and, therefore, a greater emphasis is being placed on overall health and quality of life. Increased rates of bone loss are seen in certain cancer treatment settings. Chemotherapy-related ovarian failure, use of aromatase inhibitors (AIs), androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), and steroid use are common risk factors for cancer treatment–induced bone loss. Treatment goals may include relieving pain, improving mobility, and preventing complications associated with bone loss. Cancer also frequently metastasizes to the bone. The exact incidence is not known, but it is estimated that more than half of the people who die of cancer have bone involvement. Cancers of the breast, prostate, kidney, bladder, and lungs metastasize to bone most commonly, and pain, debility, and decreased motility are often observed as a result. Bone metastases can cause serious, irreversible complications called skeletal-related events (SREs), which include pathological fractures, radiotherapy or surgery to the bone, and spinal cord compression. Hypercalcemia is a potentially reversible complication that may occur in some patients.

1. How does bone remodeling occur under normal circumstances?

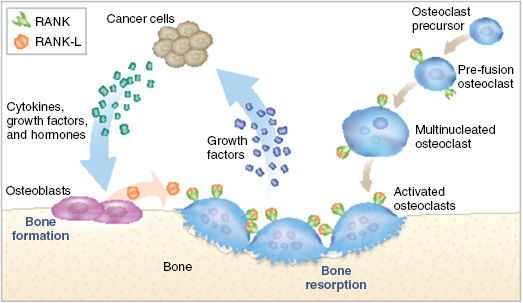

The skeletal environment comprises a dynamic interplay between bone resorption and deposition through the actions of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, respectively. Osteoclasts play an important role in bone resorption by removing bone mineral and matrix. These cells are derived from the monocyte–macrophage lineage. RANK ligand (RANKL) and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) are essential for their activation and functional integrity. Systemic factors, such as parathyroid hormone (PTH) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, upregulate RANKL and hence play a regulatory role as well. Osteoblasts are mesenchymal cells that are involved in bone deposition. Although less well understood, they are thought to rely on Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx-2) and Wnt signaling pathways for differentiation and activation.

2. How do bone metastases occur?

The skeleton is the most common site of metastasis in patients with metastatic disease, with an estimated prevalence of 1.5 million patients globally. Breast, prostate, and lung cancers most commonly metastasize to the bone. The preferential localization and growth of tumor cells in the bone are caused by the interplay between tumor cells and the bone microenvironment, a concept referred to as the “seed and soil hypothesis.” Infiltrating tumor cells secrete regulatory and growth factors such as parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP), interleukin-6 (IL6), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which in turn upregulate RANKL from newly synthesized osteoblasts. RANKL binds to its receptor RANK on the surface of osteoclasts, thereby increasing osteolysis, which leads to the release of growth factors that can promote tumor cell growth (Figure 136.1), ultimately leading to what has been termed “the vicious cycle.”

The consequences of bone metastases can be devastating, as described in this patient case. Although only 5% of women with breast cancer in the United States present with stage IV disease, approximately 25% of patients who are diagnosed with earlier-stage disease will develop metastatic disease in their lifetime. The most common site of metastases for breast cancer is bone, which can lead to pain, spinal cord compression, or fracture. The term “skeletal-related event” (SRE) is often used to describe complications of bone metastases. SREs are usually defined as a fracture, prophylactic surgery to prevent or treat a fracture, radiation to the bone to prevent a fracture or treat pain, and/or spinal cord compression. Sometimes, hypercalcemia of malignancy, secondary to bone metastases, is also included in this definition.

Spinal cord compression is a neurosurgical emergency. Of the patients with metastatic disease to the bone, 40% develop vertebral metastases and an estimated 10–20% of these patients will develop spinal cord compression. Pain usually starts several weeks before the onset of neurological deficits, and therefore new vertebral pain in a patient with known bone metastases should be evaluated promptly; particularly if the pain is worse at night or is triggered by activities that increase intradural pressure (e.g., sneezing or defecation). Although this patient presented to the emergency room, and it appears most likely that her cord compression is due to L2–L4 compression fracture, it is important that such a patient undergo a sagittal screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the complete spine. The source of her spinal cord compression could be due to epidural disease elsewhere, such as in the lower thoracic spine. This patient’s potential to recover neurological function will be based upon the speed with which the pressure of the bone metastases on her spinal cord can be surgically relieved. Unfortunately, even in a patient with known metastatic cancer, delays in diagnosing spinal cord compression often occur. These are likely due to delays in evaluation, as “pain and weakness” may be mistakenly attributed to the expected sequelae of progressive disease and chemotherapy and due to a lack of awareness that spinal cord compression represents a neurosurgical emergency. It is important that patients be educated about the symptoms of this potential risk and that triage staff understand the importance of this bone complication.

3. How are metastatic bone lesions characterized?

Bone lesions can be characterized as osteolytic or osteoblastic based on how they appear radiographically. Osteolytic lesions are characterized by bone destruction and osteoblastic lesions by abnormal bone deposition. In certain tumor types, metastatic bone disease can be predominantly osteolytic or osteoblastic; for example, osteolytic metastases are most commonly seen in breast, lung, renal, and thyroid cancers, and in multiple myeloma, whereas prostate cancer leads to the formation of osteoblastic foci in bone. Some lesions can have both osteoblastic and osteolytic features. For example, although the lesions in the breast cancer case described above were considered to be osteoblastic, this patient likely had a mix of both osteoblastic and osteolytic lesions.

4. What is cancer-treatment induced bone loss, and which patients are at risk?