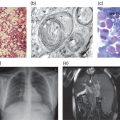

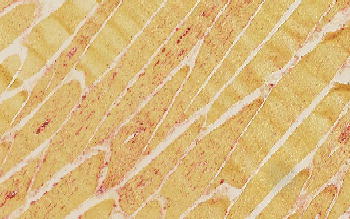

Figure 13.1 Muscle biopsy of a patient with Pompe disease. Routine staining with haematoxylin-eosin does not always reveal the pathologic abnormality but staining the lysosomes for acid phosphatase activity, as in this muscle biopsy specimen, usually reveals intensive staining (reddish colour).

Case histories

Confusing nomenclature

Unfortunately, the nomenclature used to cover the clinical spectrum of Pompe disease is confusing. Originally, Pompe disease or glycogenosis type II referred to infants with onset of symptoms shortly after birth, and the following characteristics: generalized hypotonia, cardiomegaly, and a life expectancy of less than one year. Later, “muscular variants” were described without cardiac involvement. In 1963, acid α-glucosidase deficiency was discovered as the very first lysosomal enzyme deficiency and as causative for Glycogen Storage Disease type II (Pompe disease). In 1968, the term Acid Maltase Deficiency became established among neurologists to describe adult, i.e. late-onset, variants of Pompe disease. Childhood and juvenile became widely accepted adjectives to bridge the gap between infantile-onset and late-onset disease.

The confusion started when, for the purpose of clinical trials of enzyme replacement therapy, patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and onset of symptoms under the age of 1 year were said to have infantile-onset Pompe disease, and all with onset of symptoms above the age of 1 year to have late-onset disease. At present, veterans in the field adhere to the historic definition that late-onset Pompe disease, or Acid Maltase Deficiency, is typically a disease of adulthood. Others have adopted the new definition that late-onset Pompe disease is defined by onset of symptoms above the age of 1 year, and yet others argue that late-onset Pompe disease can manifest even before the age of 1 year.

Key message: information contained in publications on late-onset Pompe disease should be interpreted according to the definition of late-onset disease as set forth in that particular publication. Publications about patients with infantile onset Pompe disease may include patients who do not have the classic-infantile phenotype.

Epidemiology

Accurate numbers on the prevalence of rare diseases are difficult to obtain. Based on the birth prevalence of three common mutations in the Dutch population, an estimated frequency of 1:40,000 was obtained in the Netherlands, divided between 1:138,000 for the classic-infantile phenotype and 1:57,000 for the less progressive phenotypes. A study in the New York population based on a larger number of then known mutations came to a similar estimate. An Australian study counting the actual number of diagnosed and registered cases in that country indicated a much lower prevalence of 1:146,000. The birth prevalence of Pompe disease derived from two recently conducted newborn screening activities in Taiwan and Austria was 1:20,000 and 1:9,000, respectively.

Pompe disease is pan-ethnic. Certain pathogenic GAA sequence variations prevail in certain ethnic communities, and some are interestingly linked to migration patterns of people around the globe.

Genetic basis

The acid α-glucosidase gene (GAA ref seq Y00839/M34424) is located on chromosome 17 q25.3 and encodes a protein of 952 amino acids that is glycosylated at seven different sites. As at June 2012, the Pompe Disease Mutation Data at www/pompecenter.nl lists 310 pathogenic sequence variations and 93 non-pathogenic variations. c.-32-13 T > G is by far the most common pathogenic sequence variation in the Caucasian population. The nonsense mutation c.2560 C > T (p.Arg854X) is the most common mutation in Afro-Americans, and c.1935 C > A (p.Asp645Glu) is widely encountered in Taiwanese, Chinese, and other Asian populations excluding the Japanese. In addition, a number of mutations are known to be more frequent in some countries than in others. Knowledge of the frequencies of mutations in ethnic populations has lost significance for diagnostic purposes, as it is presently more efficient and almost equally costly to perform whole gene sequencing than to selectively screen for specific mutations.

Pathophysiology

The acid α-glucosidase deficiency is genetically determined and almost always equally severe in all cell types. Consequently, the lysosomal glycogen storage manifests in all cell types. It is remarkable that symptoms related to central nervous system dysfunction do not dominate the clinical picture since massive glycogen storage has been demonstrated in motor neurons of severely affected infants. With regard to the preferential muscle pathology, some evidence has been presented that the muscle weakness followed by muscle wasting is brought about by the expanding lysosomal system within the muscle fibre. It hampers linear force transduction and ultimately damages the delicate organization of the contractile elements. Circumstantial evidence has been presented that genetic and non-genetic factors can modify the clinical course; patients with the same GAA genotype can have a widely different age of onset and rate of disease progression, provided that acid α-glucosidase is not fully deficient.

Clinical presentation

For practical reasons it is best to describe the disease by age category. Patients with classic-infantile Pompe disease present shortly after birth as floppy babies. They all have cardiac hypertrophy, feeding difficulties, and they do not achieve major developmental milestones including sitting, standing and walking. They typically succumb before the age of 1 year due to cardio-respiratory insufficiency. Severely affected infants with early-onset but without cardiac involvement survive longer. They usually develop a childhood phenotype characterized by progressive skeletal muscle weakness affecting their pulmonary function and leading to ventilator dependency. There are also patients who are diagnosed in infancy, mostly based on poor motor development, but who progress very slowly and continue into adulthood without medical intervention. Using the historic nomenclature, adult-onset or late-onset cases of Pompe disease are typically diagnosed in early or late adulthood with an age range from 20 to 70 years at the time of diagnosis. They present with proximal muscle weakness, most prominently in the limb-girdle region, leading to a rather characteristic waddling gate and a Gower sign. Pulmonary function is usually compromised, especially when measured in the supine position. Some patients present with shortage of breath. Extreme fatigue or muscle cramps can also be the first sign of Pompe disease. Thus, Pompe disease patients may present to a range of clinical specialities in very different age categories (Box 13.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree