Geriatric Oncology

University of Rochester James P. Wilmot Cancer Center, Rochester, NY, USA

1. What is geriatric oncology, and why is it important?

By 2030, approximately 20% of the population in the United States will comprise people aged 65 years and older, and the fastest growing subgroup of the population is those aged 75 and older. It is known that cancer is a disease of aging, with approximately 60% of all cancers and 70% of cancer mortality occurring in persons aged 65 years and over. It is also well known that older age is related to differences in cancer biology, patterns of care, and outcomes. Age is an independent predictor of distant metastases in prostate cancer, even after initial treatment. In non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, one of the negative prognostic factors for outcomes is age >65 years. In the realm of leukemia, older patients have more adverse effects from intensive treatment compared to younger patients. There are multiple factors that may be linked to the higher incidence and prevalence of cancer in the elderly population, including a decline in immune system function, longer duration of carcinogenic exposure over lifetime, altered DNA repair mechanisms with increased susceptibility to carcinogens, inherited or acquired oncogene activation or amplification, and tumor suppressor genes defects.

The Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP), a Division of Cancer Treatment of the US National Cancer Institute (NCI), sponsors clinical trials of cancer treatment and helps in identifying the best treatment strategies for patients with cancer. Although, in most cases, age restriction is not a valid eligibility criterion for adult NCI trials, studies have shown that only 25–32% of participants in cancer clinical trials are elderly. This gap is especially concerning for those cancers in which a high proportion of patients are elderly. For example, although one-third of all lung cancer patients are aged 75 and older, less than 10% of patients in clinical trials are within this age range. Several reasons have been proposed to explain the paucity of elderly patients enrolled in trials, including a history of prior malignancy, comorbid chronic health, advanced stage of disease, low educational level, and perception among patients, family members, and clinicians that the tolerance to and benefit attained with aggressive treatment by older patients may not be as substantial as that seen by younger patients.

All of these factors and more have resulted in the development of geriatric oncology, a subspecialty in oncology, where clinicians are trained both as oncologists and geriatricians to recognize that aging is a highly individualized process and that age-related changes are important to indentify. Geriatric oncologists advocate the use of a comprehensive geriatric assessment is used to ensure that elderly patients with cancer are provided with the best possible care based on individual functional reserve and life expectancy.

2. What is the comprehensive geriatric assessment? Are there alternatives?

The comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is the gold standard used by geriatricians to assess a patient’s physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being (Table 128.1). The combined data from the CGA can be used to stratify patients into risk categories to better predict their tolerance to treatment, disease prognosis, and chemotherapy toxicity. The CGA can also help to identify geriatric syndromes that may complicate cancer care. CGA has been advocated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) for use with all patients aged 70 and over with health conditions other than cancer. All measures in the geriatric assessment predict morbidity and mortality in community-dwelling older adults and can be used to identify impairments that could negatively impact the outcomes of older cancer patients. Geriatric oncologists use the CGA to guide interventions to improve care. However, one criticism of the CGA is that it can be cumbersome and time-consuming to administer.

Table 128.1 Components of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA).

| Parameter assessed | Elements of the assessment |

|---|---|

| Function Physical performance: Timed Up and Go, SPPB | Performance status |

| Activities of daily living | |

| Independent activities of daily living | |

| Comorbidity | Number of comorbid conditions |

| Severity of comorbid conditions (comorbidity index) | |

| Socioeconomic conditions | Living conditions |

| Presence and adequacy of a caregiver | |

| Cognition | Folstein’s minimental status or other tests |

| Emotional conditions, anxiety | Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) |

| Pharmacy | Number of medications |

| Appropriateness of medications | |

| Risk of drug interactions | |

| Nutrition | Mini-nutritional assessment (MNA) |

| Geriatric Syndromes | Dementia |

| Depression | |

| Falls | |

| Neglect and abuse | |

| Spontaneous bone fractures |

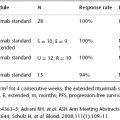

The Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) chemotoxicity assessment tool uses elements of the CGA to help risk stratify elderly patients. This tool assesses the likelihood of older cancer patients developing grade 3–5 toxicity from standard treatment. Another tool available is the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH), which looks at laboratory test values and geriatric assessment parameters besides age, such as functional and nutritional status, comorbidity, cognition, psychological state, and social support to help the oncologist objectively decide whether treatment is beneficial for the older cancer patient. Both these tools are less time consuming and easier to interpret than the CGA, thereby making them accessible to oncologists in the community with limited resources.

3. What factors affect health status in older adults?