Definitions

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined palliative care in 2005 as ‘the approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and thorough assessment and treatment of pain and other problems – physical, psychosocial and spiritual.’

Palliative care:

- provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

- affirms life and regards dying as a normal process

- intends neither to hasten nor postpone death

- integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care

- offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death

- offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and their own bereavement

- uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families

- enhances quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of the illness

- is applicable early in the course of an illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, e.g. chemo-or radiotherapy, and includes investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications.

Palliative care requires a multidisciplinary team. Good communication skills are needed to allow patients to tell their own story, discover their preferences for involvement in decision-making and goals of care, and to impart bad news sensitively and honestly (Figure 12.2). Attention to detail is vital, especially with symptom management.

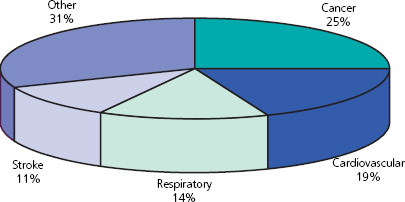

Figure 12.1 Causes of death in the UK.

Who provides palliative care?

Most patients receive palliative care from their general practitioners and/or hospital teams. End of life initiatives, such as the Gold Standards Framework and Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying, have been implemented to support palliative care in these settings (Box 12.1). Referral to specialist palliative care teams should be considered for patients with physical, psychological, social or spiritual needs that cannot be met by their current healthcare teams.

Specialist palliative care (SPC) services are needs based rather than diagnosis based. They include hospices, as well as community and hospital palliative care teams. Hospices provide inpatient services for patients requiring management of complex needs, terminal care or rehabilitation, with an average length of stay of approximately 2 weeks. Many patients are discharged home following a hospice stay. Day care, bereavement support and complementary therapies may also be available.

Figure 12.2 Effective communication skills are needed.

Box 12.1 The Gold Standards Framework and Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying

Gold Standard Framework

- Local community-based system to improve and optimise organisation and quality of care for patients in the last year of life

- Inclusion criteria are all patients who are expected to die in the next year

- Focuses around communication, co-ordination, control of symptoms, continuity (including out of hours), continued learning, carer support and care in the dying phase

- Advance care planning, symptom relief and home support become priorities and targets for quality improvement

- Further information is available at www.goldstandardsframework.nhs.uk

Liverpool Care Pathway

- Transfers best practice for care of the dying in a hospice environment to other care settings

- Inclusion criteria are dying patients with advanced progressive disease with no reversible cause

- Multiprofessional team must agree the patient is dying

- Includes proactive prescribing for common end of life symptoms – pain, nausea and vomiting, excessive respiratory secretions and agitation

- Addresses spiritual care and carers’ needs

- Further information available at www.lcp-mariecurie.org.uk

Community and hospital SPC teams have a mainly advisory role. They also have an important role in education. SPC services have expertise in the management of complex symptoms, whether physical and/or psychological, including pain that is difficult to manage, prescribing at the end of life, and can also offer an outside perspective or second opinion.

Box 12.2 Special considerations in palliative care for older people

The patient

- Impaired homeostasis (see Chapter 1)

- Cognitive impairment is common

- Symptoms such as pain and insomnia may be seen as ‘normal’ consequences of ageing

- Activities of daily living are affected more by the same symptom burden than in younger patients

The family

- Older carers, who may not be in good health

- Many patients live alone

The disease

- Increased co-morbidities

- Prognostication is more difficult in non-cancer diagnoses such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and end-stage heart failure

Drugs

- Increased number of drugs – therefore higher potential for interactions

- Different pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (see Chapter 2)

- Renal impairment is common

- Concordance may be a problem

Communication

- Hearing loss and visual impairment are common

- Subjective assessment of symptoms requires intact cognition

- Preferred decision-making styles vary with age

Palliative care in older people

The majority of patients requiring palliative care are old, and special consideration needs to be given to their assessment and management because of differences in physiology, co-morbidities and social circumstances. Box 12.2 outlines some of the differences that need to be taken into account.

Symptom management

Symptoms are common at the end of life. Approximately 70% of cancer patients and 65% of patients with non-malignant diseases will experience pain during the course of their illness. Pain and other symptoms should be considered as a total experience, with physical, psychological, social and spiritual components. The pharmacological management of pain uses the stepwise approach of the WHO pain relief ladder, starting with non-opioid analgesics and progressing to increasingly strong opioids, ensuring that drugs are prescribed both regularly and as required (see Figure 12.3).

Morphine remains the opioid analgesic of choice for moderate to severe cancer pain, but interindividual variability in absorption, metabolism and excretion may lead to a poor analgesic response or signs of toxicity in up to one-third of patients. In this situation a switch to a different kind of opioid will be necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree