Age-related differences

There are important differences in the physiology and presentation of older people that every clinician needs to know about. These in turn affect assessment, investigations and management (Box 1.1).

Special features of illness in older people include the following.

Multiple pathology

Older people commonly present with more than one problem, usually with a number of causes. A young person with fever, anaemia, a heart murmur and microscopic haematuria may have endocarditis, but in an older person this presentation is more likely to be due to a urinary tract infection, aspirin-induced gastritis and aortic sclerosis. Never stop at a single unifying diagnosis – always consider several.

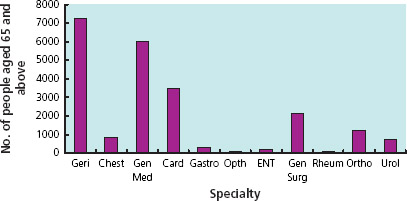

Figure 1.1 The numbers of people aged 65 and above admitted to a general hospital each year, by specialty. (Figures from the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.) Geri, geriatric medicine; Chest, chest medicine; Gen Med, general medicine; Card, cardiology; Gastro, gastroenterology; Opth, ophthalmology; ENT, ear, nose and throat; Gen Surg, general surgery; Rheum, rheumatology; Ortho, orthopaedics; Urol, urology.

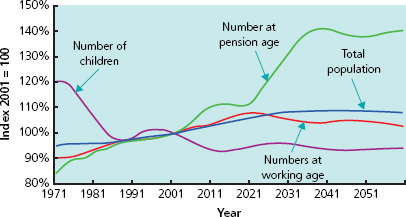

Figure 1.2 Changes in the proportion of people aged 65 and above among the overall population. Information from The UK National Census (2001).

Atypical presentation

Older people commonly present with ‘general deterioration’ or functional decline. Acute disease is often masked but precipitates functional impairment in other areas. Therefore atypical presentations such as falls, confusion or reduced mobility are not social problems – they are medical problems in disguise (Box 1.2). Often the history has to be sought from relatives and carers, over the telephone if necessary.

Box 1.1 Atypical presentation

An 85-year-old lady was recovering from surgery on an orthopaedic ward when she became withdrawn and stopped eating and drinking. Before this she had been well and mobilising. Her temperature, pulse, blood pressure and ‘routine bloods’ were normal. Her carers thought she was acting as if she wanted to die. However, it was later noted that her respiratory rate was high and a subsequent chest X-ray showed pneumonia. The patient was treated with antibiotics and recovered.

Box 1.2 Joint statement from the Royal College of Physicians and British Geriatrics Society on Intermediate Care, 2001

‘At the core of geriatric medicine as a specialty is the recognition that older people with serious medical problems do not present in a textbook fashion, but with falls, confusion, immobility, incontinence, yet are perceived as a failure to cope or in need of social care. This misconception that an older person’s health needs are social leads to a prosthetic approach, replacing those tasks they cannot do themselves rather than making a medical diagnosis. Thus the opportunity for treatment and rehabilitation is lost, a major criticism of some current services for older people. Old age medicine is complex and a failure to attempt to assess people’s problems as medical are unacceptable…Deficiencies in medical care can lead to failure to make a diagnosis; improper and inadequate treatment; poor clinical outcomes; inappropriate or wasteful use of scarce resources; communication errors and possible neglect.’

Reduced homeostatic reserve

Ageing is associated with a decline in organ function with a reduced ability to compensate. The ability to increase heart rate and cardiac output in critical illness is reduced; renal failure due to medications or illness is more likely; salt and water homeostasis is impaired so electrolyte imbalances are common in sick older people; thermoregulation may also be impaired. In addition, quiescent diseases are often exacerbated by acute illness; for example heart failure may occur with pneumonia and old neurological signs may become more pronounced with sepsis.

Impaired immunity

Older people do not necessarily have a raised white cell count or a fever with infection. Hypothermia may occur instead. A rigid abdomen is uncommon in older people with peritonitis – they are more likely to get a generally tender but soft abdomen. Measuring the serum C-reactive protein can be useful when screening for infection in an older person who is non-specifically unwell.

Some clinical findings are not necessarily pathological

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree