COMMON PSYCHIATRIC SYNDROMES IN THE ONCOLOGY SETTING

Adjustment Disorder

This is a time-limited, maladaptive reaction to a specific stressor that typically involves symptoms of depression, anxiety, or behavioral changes and impairs psychosocial functioning. The diagnostic criteria include the onset of symptoms within 3 months of the stressor but the duration of symptoms is no more than 6 months.

Management

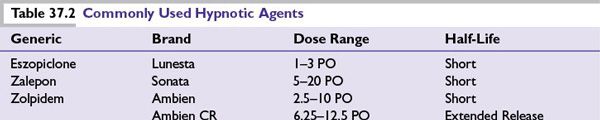

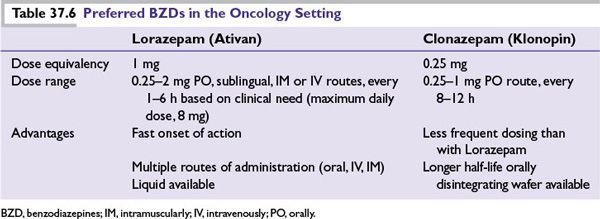

The initial treatment approach includes crisis intervention and brief psychotherapy. Time-limited symptom management with medications may be indicated. For example, anxiety, tearfulness, and insomnia are frequent reactions to the diagnosis of a new or recurrent malignancy. Short-term treatment of these symptoms with BZDs (e.g., lorazepam and clonazepam) is appropriate, effective, and rarely associated with the development of abuse or dependence. Short-term use of non-BZD sleep agents (e.g., zolpidem, eszopiclone) is also commonplace in clinical practice (Table 37.2).

Major Depression

Major depression and subsyndromal depressive disorders are common in patients with cancer. Prevalence rates vary between 5% and 50% depending on how depression is defined, whether study samples are drawn from outpatient clinics or hospital wards and the type of cancer involved. Untreated depression has been correlated with poor adherence with medical care, increased pain and disability, and a greater likelihood of considering euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Recent studies suggest that depression is also associated with increased mortality in patients with cancer.

A frequent diagnostic task in the oncology setting is differentiating symptoms of major depression from those symptoms that are caused by the underlying cancer or its treatment. Patients with cancer, especially those with advanced disease who are undergoing chemotherapy, are more likely to experience fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and insomnia, whether a major depression is present or absent. Our practice is to institute empiric trials of antidepressants using a targeted symptom-reduction approach. In questionable cases, a personal or family history of depression and the presence of symptoms of excessive guilt, poor self-esteem, anhedonia, and ruminative thinking strengthen the argument for a medication trial. Furthermore, because the number of well-tolerated, safe, and effective antidepressants has grown, we have lowered our threshold for treating subsyndromal depression in the oncology setting.

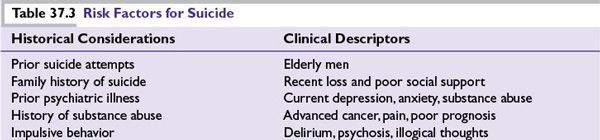

Because patients with cancer have an increased risk of suicide compared with the general population, particular attention should be paid to symptoms of hopelessness, helplessness, suicidal ideation, and intense anxiety (Table 37.3). Cancer at certain sites, including lung, gastrointestinal tract, and head and neck cancers, is associated with an even greater risk of suicide. Risk of suicide appears to be highest immediately after diagnosis and decreases thereafter but remains increased for years as compared to suicide rates in the general population. Suicide rates are higher among patients with advanced disease at diagnosis but not among patients with multiple primary tumors. Other risk factors for suicide include male sex, white race, and being unmarried, similar risk factors for suicide in the general population. In addition, adult survivors of childhood cancers are at increased risk for suicidal ideation related to cancer diagnosis as well as posttreatment mental and physical health problems, even many years after completion of therapy.

Management

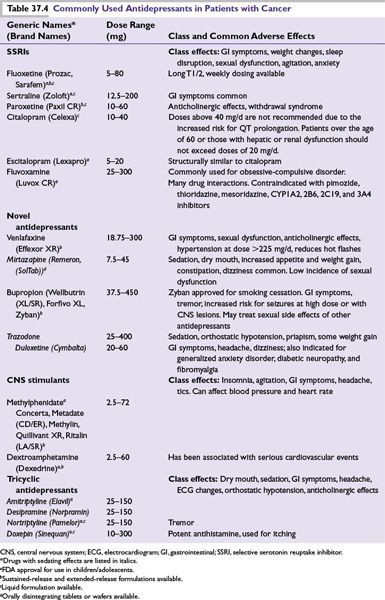

Treatment modalities include pharmacotherapy (Table 37.4) and psychotherapy. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is highly effective in the treatment of major depressive disorder resistant to pharmaco- and psychotherapy. Selection of an antidepressant in major depression should be based on a number of considerations such as active medical problems, the potential for drug interactions, prior treatment response, and an optimal match between the patient’s target symptoms and the side-effect profile of the antidepressant (e.g., using a sedating agent for the patient with anxiety and insomnia).

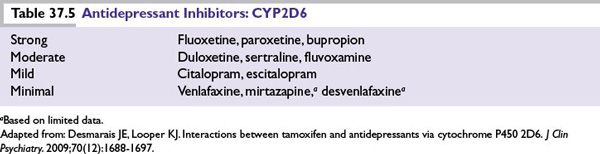

Potential interactions with cancer therapeutics should also be considered. For example, several antidepressants are inhibitors of cytochrome P-450 2D6. This inhibition reduces the metabolism of tamoxifen to its active metabolite, endoxifen. Venlafaxine (Effexor) has the least inhibitory effect at 2D6 and thus is preferred in breast cancer patients taking tamoxifen (Table 37.5).

An antidepressant frequently used in patients with cancer is mirtazapine (Remeron) as it is sedating, causes weight gain, has few significant drug interactions, and is a 5HT-3 receptor antagonist (i.e., has antiemetic properties). Mirtazapine may also be used as an augmentation agent for depression treatment in conjunction with SSRIs. Elderly patients or patients with medical comorbidities (especially hepatic impairment) generally require smaller dose of antidepressants.

Anxiety Disorders

Many medical conditions seen in the oncology setting, such as heart failure, respiratory compromise, seizure disorders, pheochromocytoma, and chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure, may cause anxiety. Additional conditions that may cause both anxiety and depression are listed in Table 37.1. Similarly, anxiety is an adverse effect of numerous medications such as high-dose corticosteroids. In particular, dopamine-blocking antiemetics may cause akathisia, an adverse effect characterized by subjective restlessness and increased motor activity, which is commonly misdiagnosed as anxiety. Initiation of treatment with an antidepressant may also induce a transient anxiety state. It is important to inform patients of this potential side effect in order to improve adherence.

Management

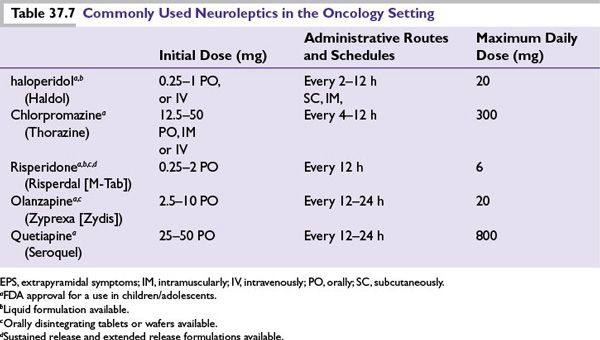

In addition to behavioral therapy and psychotherapy, BZDs are the medications that are most frequently used for the short-term treatment of anxiety (Table 37.6). For anxiety that persists beyond a few weeks, treatment with an antidepressant (see Table 37.4) is indicated. BZDs are often started concurrently with an antidepressant as a “bridge therapy” as there is a typical delay in therapeutic effect for antidepressants of up to several weeks. If the patient has already been taking an SSRI, it is important not to discontinue it (with the exception of fluoxetine because of its long half-life) abruptly to avoid a withdrawal syndrome that may include gastrointestinal distress, flu-like symptoms, insomnia, agitation, and irritability. Low-dose second-generation antipsychotics are often useful for severe and persistent anxiety or for conditions such as anxiety secondary to steroids and delirium (Table 37.7).

The following issues associated with BZD use require attention:

■BZDs are the treatment of choice for delirium caused by alcohol or sedative–hypnotic withdrawal but predictably worsen other types of delirium.

■In patients with hepatic failure, lorazepam, temazepam, or oxazepam are the preferred BZDs as they do not require oxidation for metabolism.

■BZDs may result in “disinhibition,” especially in delirium, substance abuse, “organic” disorders, and preexisting personality disorders. Disinhibition is more common in children and elderly patients.

■The abrupt discontinuation of BZDs with short half-lives (e.g., alprazolam [Xanax]) can cause rebound anxiety and precipitate a withdrawal syndrome.

■Long-term use of BZDs may lead to cognitive problems, tolerance, and dependence. Time-limited use is recommended.

Delirium

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree