FIGURE 14.1 Treatment options for patients diagnosed with localized prostate therapy. RT can include EBRT or brachytherapy (generally reserved for select patients with intermediate- or low-risk disease), or a combination of the two in some high-risk cases.

Surgical Complications

■Immediate morbidity or mortality: 2%.

■Impotence: 35% to 60%.

■Urinary incontinence: 10% with frank incontinence; up to 60% require protective garments.

■Urinary structure.

■Fecal incontinence: retropubic approach, approximately 5%; perineal approach, 18%.

■The Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study found statistically significant differences in outcomes following RP or RT. For patients with normal baseline function, RP was associated with inferior urinary function, better bowel function, and similar sexual dysfunction compared with RT.

Focal Therapy for Disease Confined to a Region of the Prostate

Focal therapy for newly diagnosed CaP confined to a limited area of the prostate remains investigational. This strategy is different from other therapies for localized disease in that only a focal region of the prostate, as opposed to the entire glad, is targeted with hopes of limiting side effects. Cryosurgery destroys CaP cells through probes that subject prostate tissue to freezing followed by thawing. This procedure is associated with high rates of erectile dysfunction due to freezing of the neurovascular bundle. Additional focal therapy strategies include thermal ablation via laser or high-intensity focused ultrasound among other techniques. There are limited data on long-term outcomes for focal therapy. Thus, at most centers prostate focal therapies are largely performed as salvage procedures.

Radiation Therapy

External Beam RT

■External beam RT (EBRT) targets the whole prostate, frequently including a margin of extraprostatic tissue, seminal vesicles, and pelvic lymph nodes.

■Higher doses (≥78 Gy) given over approximately 8 weeks are associated with higher PSA control rates; however, survival data are not mature.

■Three-dimensional (3D) conformal RT allows for maximal doses conforming to the treatment field, while sparing normal tissue.

■Intensity-modulated RT is a type of 3D conformal RT that is designed to conform even more precisely to the target.

■Unlike x-rays, which radiate beyond the target volume, proton beam irradiation focuses virtually all its energy within a very small area, thus theoretically minimizing damage to normal tissue.

RT with Adjuvant ADT

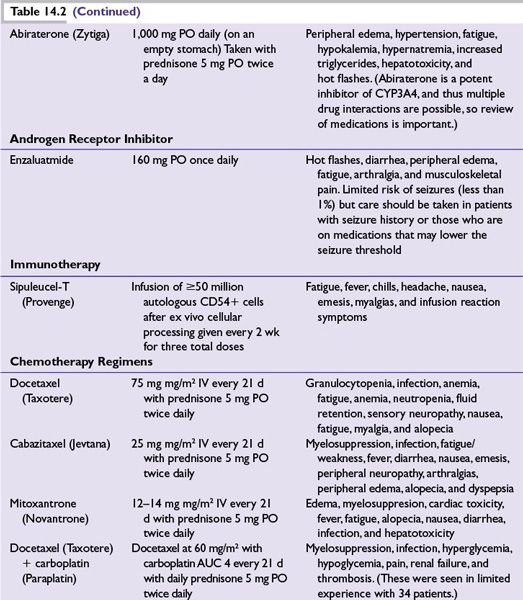

At least three randomized controlled trials have shown that combining ADT with RT in patients at high risk for recurrent disease (Table 14.1) improves OS. ADT is usually given during RT and for 2 to 3 years thereafter. It may also be used for 2 months prior to RT to help decrease tumor size and thus the target volume of RT.

Adjuvant RT

■General indications for the use of adjuvant RT after RP include positive surgical margins, seminal vesicle involvement, and evidence of extracapsular extension. Nonetheless, the potential for cure with adjuvant RT will vary significantly from patient to patient and thus the risks and benefits of adjuvant RT should be evaluated in each case individually.

Salvage RT

For select patients with rising PSA after RP and a high likelihood of organ-confined local recurrence (e.g., PSA <1.5 and slowly rising), salvage RT may be considered. However, there are limited data on which to make recommendations.

Brachytherapy

Interstitial brachytherapy with radioactive palladium or iodine seeds that delivers a much higher dose of radiation to the prostate is used in CaP patients with low-risk tumors and some intermediate-risk patients. Better definitions of tumor volume and radiation dosimetry have made this outpatient technique more accurate. CT and/or transrectal ultrasound are used to guide seed placement.

Combined EBRT and Brachytherapy

EBRT followed by brachytherapy boost is an increasingly used strategy. Preliminary clinical data support the safety and efficacy of this approach in a selected population of patients. Long-term clinical data including OS data from randomized trials are still pending. Nonetheless, some radiation oncologists are using this treatment combination in patients with high-risk disease.

Complications of RT

Acute

■Cystitis

■Proctitis/enteritis

■Fatigue

Long term

■Impotence

■Incontinence (3%)

■Frequent bowel movements (10% more than with RP)

■Urethral stricture (RT delayed 4 weeks after transurethral resection of the prostate)

COMPARISON OF PRIMARY TREATMENT MODALITIES

Comparing treatment modalities in terms of overall and disease-free survival is difficult because of differences in study design, patient selection, and treatment techniques.

■While there have been no satisfactory randomized trials comparing RT with RP, these approaches appear to have equivalent PSA-free survival (also called biochemical relapse-free survival) in appropriately matched patients at 5 years, but differ in type and frequency of side effects.

■Brachytherapy appears promising, although most studies have been conducted only in patients with early-stage, low-grade disease. One comparison of 3D conformational RT with 125I implants in comparable patients concluded that these modalities had equivalent efficacy, with higher urinary complications in the brachytherapy group.

FOLLOW-UP AFTER DEFINITIVE TREATMENT

■Patients treated with curative intent should have PSA levels checked at least every 6 months for 5 years, then annually. Annual DRE is appropriate for detecting recurrence.

■After RP, a detectable PSA suggests a relapse. PSA failure after RT is defined as 2 ng/mL over the nadir, whether or not the patient had ADT with RT.

TREATMENT FOR MEN WITH RISING PSA AFTER LOCAL THERAPY

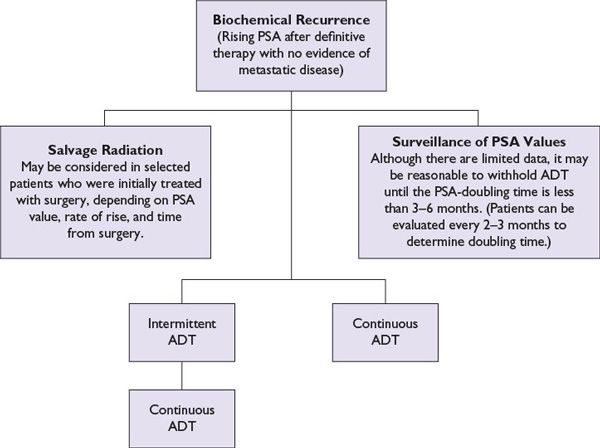

Treatment for patients who have rising PSA (biochemical failure) after local therapy has not been standardized and participation in clinical trials should be encouraged (Fig. 14.2). As previously mentioned salvage RT, salvage RP, or salvage focal therapy may be offered to select patients with local recurrence. ADT effectively lowers PSA and can be given intermittently to provide periods of normal testosterone. Based on preliminary results from randomized studies, CaP-specific outcomes with intermittent and continuous ADT appear to be similar. However, there are no data suggesting better survival with ADT than with no ADT. Recent data suggest that on average, men live about 14 years after biochemical failure. Thus a more conservative approach (e.g., treating when symptomatic) is a reasonable option for many men. Alternatively, using PSA-doubling time (i.e., less than 3 to 6 months) as a trigger to initiate ADT or intermittent ADT is frequently done in clinical practice; however, no randomized trials have prospectively evaluated this approach relative to continuous or delayed ADT based on doubling time.

FIGURE 14.2 Treatment options for biochemical recurrence/nonmetastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Continuous ADT employs repeated doses of GnRH agonists/antagonists to provide a constant testosterone suppression. Orchiectomy would also be an option. Intermittent ADT employs two or three doses of testosterone-lowering therapy, which are then discontinued if the PSA declines as expected. From there, PSA slowly recovers, lagging behind testosterone recovery. In selected patients, this approach can be used to alleviate some ADT toxicity. ADT is often reinstituted based on a PSA doubling time similar to the “surveillance of PSA” approach described in the figure.

Response Criteria: Using PSA, a Historical Perspective

Only 40% of patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), or progressing disease despite castrate levels of testosterone, have soft tissue disease. Therefore, PSA historically has been an important tumor marker for preliminary assessment of efficacy in proof-of-principle trials. PSA response rates (PRRs) are defined as percentage of patients with a PSA decline >50%, a traditionally used criterion. Because of differences in patient selection, it is difficult to compare clinical trials by PRRs alone. Many trials now include all PSA declines in a “waterfall plot.” It is important to note that some agents (particularly cytostatic agents) may upregulate or downregulate PSA expression independent of their effect on cancer growth. Definitive studies historically have utilized skeletal-related events, palliation of symptoms, or OS for CRPC.

EVOLUTION OF RESPONSE CRITERIA IN METASTATIC DISEASE

The Prostate Cancer Working Group 2 and the Implications for Clinical Practice

■As the understanding of CaP has evolved in the last decade, in the context of new available therapies and greater experience with older therapies, a general consensus was generated by Prostate Cancer Working Group 2 (PSWG2) on determining response in clinical trials.

■Perhaps most importantly, PSA should not be used as the sole criteria to discontinue a therapy. Furthermore, the PSWG2 recommends that early changes in PSA and modest increases in pain, which could represent a tumor flare phenomenon, should not result in the discontinuation of therapy.

■For patients with metastatic CaP, objective changes on imaging studies (CT and bone scan) should be the primary criteria used to assess progression of disease in the absence of clear clinical progression of symptoms.

■In order to assess imaging, lymph nodes less than 2 cm in diameter are too small to be evaluated for response or progression of disease.

■Two new bone lesions on bone scan are required to document progressive disease, with one important exception. New lesions on the first bone scan should trigger another bone scan 6 or more weeks later, as these new lesions may have been present on the first scan, but missed on initial imaging or they may represent a the “tumor flare phenomenon.” If the second (and subsequent) bone scans show less than two new lesions and the patient is otherwise clinically stable, he should be considered to have stable disease.

■For the treatment of patients outside of clinical trials the implications of the PCWG2 are as follows:

•Radiographic response criteria should be used to determine disease progression in metastatic CaP as opposed to PSA alone.

•Initial changes on bone scan are not sufficient to remove patients from a treatment; patients could continue therapy if subsequent bone scans show less than two new lesions.

•Changes in lymph nodes less than 2 cm in diameter should be interpreted with caution.

•PSA should still be followed but interpreted with caution and not be used as the sole criteria to determine when to discontinue a therapy.

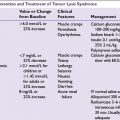

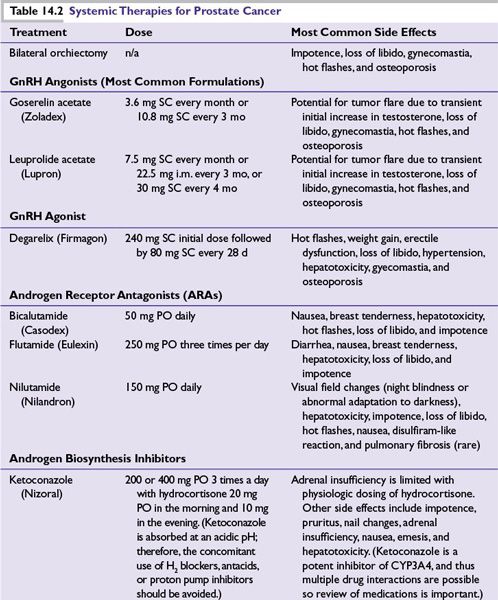

■ADT is the mainstay of treatment for metastatic CaP (Table 14.2). However, as discussed previously, it has also been used to treat localized disease and in neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings with RT. CaP cells usually respond to hormonal manipulations that block the production of androgens, producing durable remissions and significant palliation. Duration of response ranges from 12 to 18 months, with 20% of patients having a complete biochemical response at 5 years. However, ultimately, CRPC cells emerge and lead to disease progression.

■Bilateral surgical castration and depot injections of GnRH agonists (e.g., leuprolide, goserelin, and buserelin) and a GnRH antagonist (degarelix) provide equally effective testosterone suppression. Combined androgen blockade can be achieved by adding an oral androgen receptor antagonist (ARA; e.g., nilutamide, flutamide, and bicalutamide). However, this is controversial and provides little if any survival benefit.

■GnRH agonists initially increase gonadotropin, causing a transient (~14-day) increase in testosterone that can lead to tumor flare. A lower tumor volume reduces the risk of symptomatic tumor flare. Tumor flare can be prevented by the use of an ARA, which binds to the androgen receptor (AR), effectively stopping the ability of the AR to activate cell growth. An ARA is often given for 1 to 2 weeks prior to GnRH agonist in patients at risk for complications (pain, obstruction, and cord compression) associated with tumor flare. For high-risk patients, bilateral orchiectomy or ketoconazole can decrease testosterone more quickly.

■In patients initially treated with GnRH agonist or surgical castration alone, the addition of an ARA may produce PSA declines or symptomatic improvement in up to 40% of patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree