Disorders of the immune system, often in conjunction with chronic viral infection, are also heavily implicated in lymphomagenesis and are associated with increased risk of NHL. Significantly higher rates of NHL are seen in patients with congenital and acquired immunodeficiencies as well as diseases of immune dysregulation. Though most of these lymphomas are of B-cell lineage, there are notable exceptions such as enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL), which occurs most commonly in patients with gluten enteropathy, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL), which occurs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease or post–solid organ transplantation.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is implicated in the pathogenesis of many different subtypes of NHL that occur in the immunocompromised host. Within the HIV-infected population, EBV is strongly associated with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) and plasmablastic lymphoma, oral type. It is also seen in immunodeficient patients with primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), plasmablastic lymphoma, and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD). EBV is also pathogenically implicated in a number of NHL subtypes in immunocompetent patients. In many of these lymphomas, EBV is thought to drive lymphomagenesis by constitutively activating NF-κB and other cell signaling pathways, while in other lymphomas its pathogenic role remains unknown.

Various other infectious pathogens have also been implicated in the development of NHL subtypes, such as HHV-8 and HTLV-1. Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) is known to be antigenically driven by both viral and bacterial pathogens, to include hepatitis C virus (HCV) in splenic and nodal MZL variants, Helicobacter pylori in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, and Chlamydia psittaci in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma (OAML).

CLASSIFICATION

NHL is classified according to the 2008 update of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification system. Initially established in 2001, this system constituted the first international consensus on diagnosis and classification of lymphoma. Within this system, NHL is classified primarily by cell lineage and maturity (B- vs. T/NK cell, mature vs. precursor cell of origin) and then further subcategorized according to a combination of morphologic, immunophenotypic, genetic, molecular, and clinical features. It is expected that the current classification system for NHL will continue to evolve as our knowledge of the genetic and molecular basis of these diseases continues to improve.

DIAGNOSIS

A properly evaluated and technically adequate excisional lymph node biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis of suspected lymphoma. In recent years, some centers have adopted the practice of obtaining a combination of core-needle biopsy and fine-needle aspiration as an alternative to surgical lymph node excision, reserving the latter for nondiagnostic cases. Although this approach is relatively sensitive and cost-effective, a definitive diagnosis is unobtainable in approximately 20% to 25% of patients. Consequently, multiple factors—including include perioperative risk, institutional experience with core-needle biopsy, and risk of possible delay in diagnosis—need to be considered when deciding upon the preferred approach to biopsy.

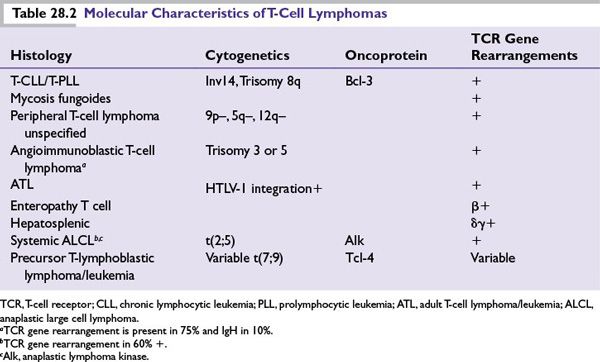

Diagnosis of NHL is achieved primarily through a combination of morphologic and immunohistochemical tissue analysis. Important additional studies for diagnostic confirmation and subclassification often include flow cytometry, cytogenetic analysis, and molecular studies. Testing for specific oncogenic chromosomal rearrangements or staining for overexpression of their corresponding oncoproteins can also be diagnostically useful in a number of NHL subtypes (see Tables 28.1 and 28.2).

WORKUP AND STAGING

Initial workup and staging evaluation of NHL should include a complete history and physical examination and clinical laboratory assessment of organ function. In addition, the following tests should be performed:

■Complete blood count with differential

■Complete metabolic panel to include lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

■Serologies for HIV, HBV, HCV (regardless of exposure history)

■CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

■Whole-body FDG-PET scan (strongly consider for aggressive lymphomas, or if concern exists for extranodal disease)

■Bone marrow (BM) aspirate and biopsy

■Lumbar puncture with CSF cytology and flow cytometry (patients at increased risk for central nervous system [CNS] disease: BL, ALL, intravascular lymphoma, elevated LDH, multiple extranodal sites, or involvement of BM, testis, or paranasal sinuses)

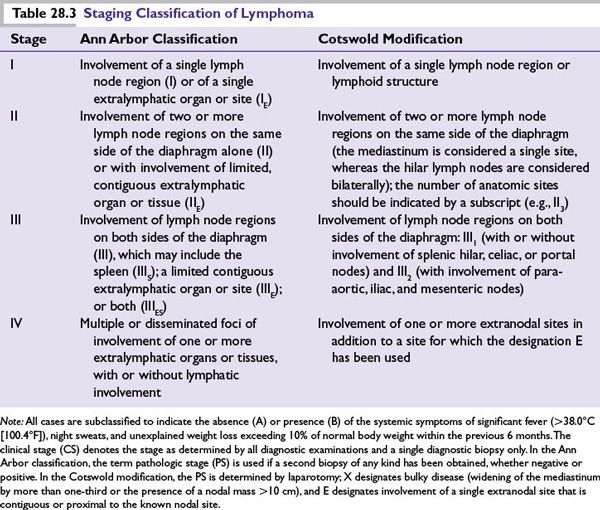

The Ann Arbor staging system, originally designed for Hodgkin lymphoma, also has prognostic and predictive utility in NHL, and its use is considered standard for newly diagnosed cases (Table 28.3). Although this system is often of limited prognostic value due to the lack of contiguous orderly spread through lymph node regions, it nevertheless remains an integral component of the validated international prognostic indices for aggressive NHL (IPI) and follicular lymphoma (FLIPI).

Restaging for Response Evaluation

Upon completion of therapy, staging studies should be repeated (CT scan and BM biopsy if positive previously). In accordance with the Revised Response Criteria for Malignant Lymphoma, FDG-PET is also useful for the evaluation of residual masses at the completion of therapy. In cases of suspected disease relapse or refractoriness to initial therapy, repeat biopsy should be performed whenever possible, both to exclude nonmalignant causes of the abnormal imaging or findings in question and to evaluate for possible transformation of disease.

PROGNOSTIC FEATURES

The International Prognostic Index (IPI) applies to untreated aggressive lymphoma. Five clinical factors comprise the IPI and 1 point is assigned to each factor:

–Age >60 years

–Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 2 or higher

–LDH level greater than normal

–Two or more extranodal sites

–Ann Arbor stage III or IV disease

Scores of 0 to 1, 2, and 3, and 4 to 5 correspond to 5-year survivals of 73%, 51%, 43%, and 26%, respectively. A validated clinical prognostic index has also been applied to patients with untreated follicular lymphoma. The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) is scored according to age, stage, serum LDH level, hemoglobin, and the number of nodal areas, and has been found to reliably predict survival. In recent years, gene expression profiling has emerged as a useful means of identifying molecularly distinct subclassifications of NHL, and is likely to either augment or supplant current prognostic and predictive tools in the future. At this time, however, this technology remains investigational and not readily applicable to standard practice.

MANAGEMENT

Indolent B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Follicular Lymphoma

FL is the most common of the indolent lymphomas, constituting approximately 70% of cases. Patients are typically older (median age of 60) with disseminated lymphadenopathy at diagnosis. Constitutional symptoms and extranodal involvement can occur, but are uncommon. Many patients are asymptomatic at diagnosis. Median survival is approximately 10 years. Histologic transformation to a more aggressive NHL subtype (typically DLBCL) occurs at an approximate cumulative rate of 3% per year. FL is graded (1–3) according to the number of centroblasts per high power field. Therapeutic approaches to grades 1 to 3A are similar, whereas grade 3B is considered a variant of DLBCL for the purposes of treatment.

FL is generally considered to be an incurable malignancy. Patients with early-stage FL, however, may achieve prolonged remissions and long-term survival with radiation treatment alone. Multiple studies have reported a 15-year overall survival rate of approximately 50% in these patients, with few relapses reported after 10 years. For patients with asymptomatic advanced-stage FL, chemotherapy has not been shown to improve OS compared to watchful waiting. In recent years, the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab, has demonstrated both safety and efficacy in follicular lymphoma with response rates of up to 73% in previously untreated patients. However, there is not yet evidence of a survival benefit to rituximab in the first-line setting in asymptomatic patients, and this approach is still considered investigational. In therapy-naive patients with symptomatic advanced FL by the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires (GELF) criteria, the addition of rituximab to chemotherapy is now considered the standard of care due to the significantly higher response rates and OS achieved over chemotherapy alone in multiple studies. Although no chemoimmunotherapy regimen has yet demonstrated superior survival over another, the combination of bendamustine and rituximab (BR), in an early report, demonstrated superior progression-free survival (PFS) and reduced toxicity compared to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and rituximab (R-CHOP) in patients with low-grade NHL (predominantly FL). Patients not able to tolerate chemotherapy may be given single-agent rituximab. Extended treatment with rituximab, or “maintenance” rituximab, has been shown to extend PFS, although no OS advantage has yet been demonstrated.

Patients with relapsed/refractory FL can be treated with combination chemoimmunotherapy, single-agent rituximab, or radioimmunotherapy. The latter involves the delivery of targeted radiotherapy to tumor tissue by conjugating an anti-CD20 antibody to a radioactive isotope. In a randomized trial of relapsed or refractory follicular or transformed lymphoma, the overall response rate was better with ibritumomab tiuxetan than with rituximab (80% vs. 56%). However, a recently published phase III intergroup trial evaluating the role of radioimmunotherapy in newly diagnosed FL patients (R-CHOP versus CHOP followed by 131Iodine tositumomab) demonstrated similar PFS and OS in both groups at median 5 years of follow-up. Further studies of radioimmunotherapy in FL should better define the true benefit and optimal use of this treatment modality.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma

SLL represents the less common lymphomatous/aleukemic phenotype of CLL and both diseases are considered to be biologically the same. Median age at diagnosis is 72, and many patients are asymptomatic at diagnosis. Similar to FL, treatment is only indicated for symptomatic disease.

CLL/SLL is a clinically heterogeneous disease, ranging from stability or slow progression for years without treatment (most commonly the 13q– variant) to rapidly progressive disease with a high degree of resistance to conventional therapy (17p– variant). Chemoimmunotherapy regimens containing fludarabine and rituximab are considered standard of care for first-line therapy. The OS benefit of adding rituximab to chemotherapy was recently demonstrated in the German CLL8 trial which randomized patients to fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) versus FC alone. FCR and FR are both acceptable first-line therapies; although rates of complete response and PFS seem to be superior with FCR, it is a more toxic regimen than FR and there has yet to be a proven survival benefit. In patients with the 11q deletion, however, recent data indicate that the inclusion of cyclophosphamide may overcome the adverse prognostic significance of this genetic lesion. In elderly patients and those unlikely to tolerate FCR, options include FR, “FCR-lite” (reduced doses of FC with higher doses of R), BR, lenalidomide, or alemtuzumab. In contrast to FL, single-agent rituximab does not possess sufficient activity to warrant its use in CLL/SLL.

For relapsed/refractory CLL/SLL, any of the aforementioned regimens or agents can be used. Additionally, the second-generation anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, ofatumumab, was recently FDA approved for CLL/SLL refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab. Compared to rituximab, ofatumumab binds with higher affinity to CD20 and has a response rate of over 50% in these “double-refractory” CLL patients. Studies combining ofatumumab with chemotherapy are ongoing.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains an option for relapsed/refractory CLL/SLL. There is evidence of a strong and durable graft-versus-leukemia effect in patients transplanted for this disease, making it the only CLL therapy capable of achieving cure. Given the substantial risks and morbidity associated with this approach, however, it is generally reserved for patients who have failed conventional therapy and those with relapsed high risk (17p–) or transformed disease.

Lymphoplasmacytoid Lymphoma/Waldenström Macroglobulinemia

This is an indolent but incurable lymphoma composed of mature plasmacytoid lymphocytes that produce monoclonal IgM. It primarily affects older patients and is most common in the Caucasian population. Patients typically present with symptoms of increased tumor burden (cytopenias due to marrow involvement, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, constitutional symptoms) and/or symptoms attributable to the secreted monoclonal immunoglobulin (hyperviscosity syndrome, autoimmune neuropathy, mucocutaneous bleeding). Asymptomatic patients are considered to have “smoldering” WM and are observed. Symptomatic disease occurs in approximately 60% of patients within 5 years after diagnosis.

Options for therapy include single-agent rituximab, chemoimmunotherapy regimens such as FR or BR, and rituximab combined with novel agents such as bortezomib. When rituximab is used, the patient must be observed carefully for development or worsening of hyperviscosity symptoms, as serum IgM levels can increase abruptly and substantially prior to declining. Plasmapheresis prior to rituximab-containing therapy should be strongly considered for any patient presenting with symptoms of hyperviscosity or high baseline serum IgM.

Marginal Zone Lymphomas

These are indolent lymphomas, comprising approximately 10% of NHL, that occur primarily in extranodal MALT (EMZL or MALT lymphomas), and to a lesser extent within the spleen (splenic MZL) and lymph nodes (nodal MZL). The majority of EMZL occurs within the gastrointestinal tract (most commonly the stomach), but can also occur in the parotid and salivary glands, thyroid, lungs, ocular adnexae, and breast, among others. Most patients present with localized disease, and 5-year survival is approximately 90%. EMZL is highly antigen driven, and a history of chronic infection such as Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis in gastric MALT lymphoma or Chlamydiphila psittaci in ocular adnexae MALT lymphoma is common. With current antibiotic regimens, the majority of patients with early-stage gastric MALT lymphoma will achieve sustained remission with bacterial eradication alone. Likewise, recent data indicate that eradication of C. psittaci

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree