FIGURE 38.1 Comparison of emetic symptom phases and antiemetic activity. Top: Temporal relation between the start of emetogenic treatment (hour 0) and emetic symptom phases. For each phase, shaded bars indicate generally when nausea and emesis occur before and after emetogenic treatment; greater intensity of shading approximates the incidence of symptoms. Bottom: The most highly active antiemetic categories ranked by relative effectiveness against acute-phase (0 to 24 hours) and delayed-phase (>24 hours) emetic symptoms.

Anticipatory Events

Anticipatory emetic symptoms occur before repeated exposure to an emetogenic treatment as an aversive conditioned response as a consequence of poor emetic control during prior therapy. Although anxiolytic amnestic drugs are helpful in preventing and delaying anticipatory symptoms, complete control throughout all antineoplastic treatments is the best preventive strategy against developing symptoms. Behavioral therapies such as relaxation techniques and systematic desensitization are recommended if symptoms occur. After symptoms develop, medical intervention during subsequent emetogenic treatment is limited to preventing the reinforcement of conditioned stimuli, which may exacerbate anticipatory symptoms.

EMETOGENIC (EMETIC) POTENTIAL

Emetic potential or risk and symptom patterns vary among medications used in antineoplastic chemotherapy and radiation therapy techniques.

Chemotherapy

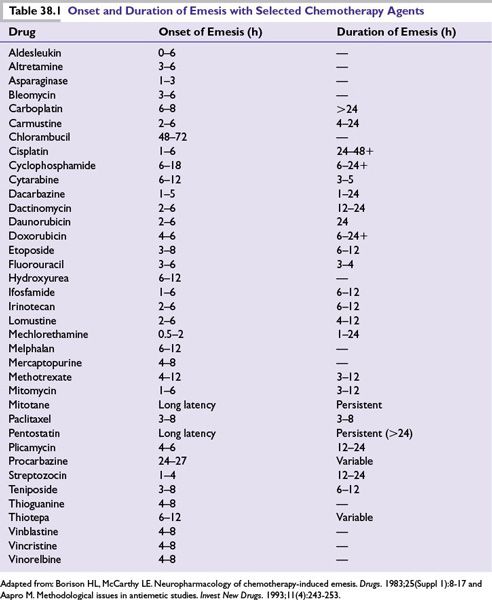

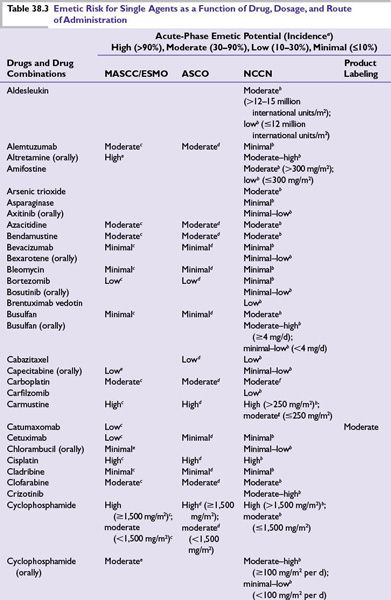

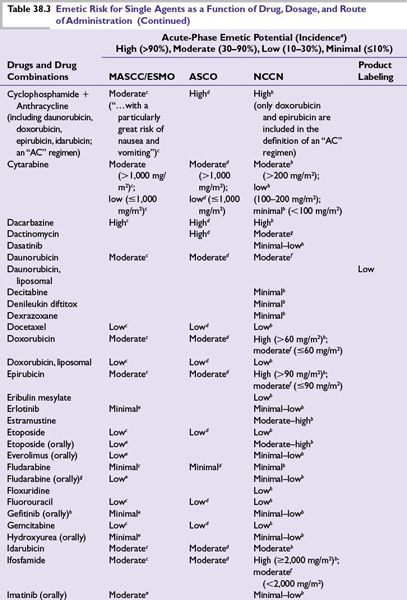

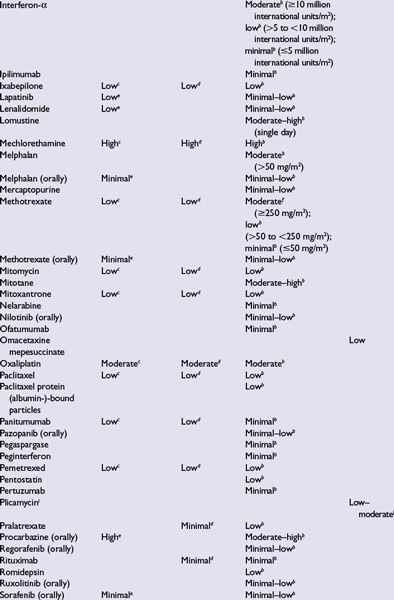

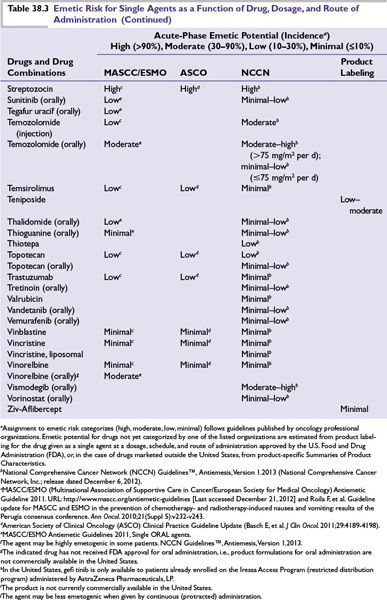

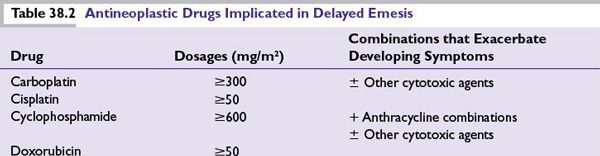

Intrinsic emetogenicity (Table 38.3) is an antineoplastic drug’s propensity for causing emetic symptoms. Drug dose or dosage is often the second most significant factor affecting emetogenic potential and the duration for which symptoms persist.

The number of emetogenic drugs used in combination, administration schedule, treatment duration, and route of administration are also mitigating factors. Emetic potential may be lessened or eliminated by protracted drug delivery over hours or days, and increased by rapid drug administration, repeated emetogenic treatments, and brief intervals between repeated doses (Table 38.3). When emetogenic treatment is given on more than 1 day, physiologic processes associated with acute- and delayed-phase symptoms may overlap and both should be considered in designing effective antiemetic prophylaxis. The potential and duration for delayed symptoms depend upon the sequence in which emetogenic drugs are administered and the emetogenic risk each drug presents.

Radiation

The emetic potential of ionizing radiation correlates directly with the amount given per dose or fraction, the total dose administered, and the rate of administration. Large treatment volumes (>400 cm2); fields including the upper abdomen, upper hemithorax, and whole body; and a history of poor emetic control with chemotherapy are risk factors for severe emesis. Emetic potential increases when radiation and chemotherapy are administered concomitantly (“radiochemotherapy”).

PATIENT RISK FACTORS

Patients at greatest risk for emetic symptoms include

■Female sex, particularly women with a history of persistent and/or severe emetic symptoms during pregnancy.

■Children and young adults.

■Patients with a history of acute- and/or delayed-phase emetic symptoms during prior treatments are at great risk for poor emetic control during subsequent treatments.

■Patients with low performance status and a predisposition to motion sickness.

■Nondrinkers are at greater risk than patients with a history of chronic alcohol consumption (>100 g ethanol daily for several years).

■Patients with intercurrent pathologies, such as gastrointestinal (GI) inflammation, compromised GI motility or obstruction, constipation, brain metastases, metabolic abnormalities (hypovolemia, hypercalcemia, hypoadrenalism, uremia), visceral organs invaded by tumor, and concurrent medical treatment (opioids, bronchodilators, aspirin, NSAIDS), may predispose to and exacerbate emetic symptoms during treatment and complicate good emetic control.

PRIMARY ANTIEMETIC PROPHYLAXIS

Primary prophylaxis is indicated for all patients whose antineoplastic treatment presents at least a low risk of producing emetic symptoms, that is, when >10% of persons receiving similar chemotherapy or radiation therapy without antiemetic prophylaxis are predicted to experience emetic symptoms (Table 38.3).

■Planning effective antiemetic primary prophylaxis

•Evaluate the emetic potential for each drug included in treatment, which includes the severity, onset, and duration of symptoms associated with individual drugs (Table 38.1), and how drug dose or dosage, schedule, and route of administration may affect those factors.

•Patients who receive combination chemotherapy should receive antiemetic prophylaxis based on the most emetogenic component of treatment.

•Include primary prophylaxis against acute-phase symptoms for all treatments with low, moderate, or high emetic potential, and delayed-phase prophylaxis for treatments with moderate or high emetic potential.

•For patients who receive antineoplastic chemotherapy and radiation concomitantly, antiemetic prophylaxis is selected based on the chemotherapy component that presents the greatest emetogenic potential, unless the emetic risk from radiation is greater.

•Patients who receive moderately or highly emetogenic treatment for more than 1 day should receive antiemetic prophylaxis appropriate for the drug with greatest emetogenic potential on each day of treatment.

•If antineoplastic treatment is associated with delayed emetic symptoms, continue antiemetic prophylaxis:

•For at least 3 days after highly emetogenic treatment is completed.

•For at least 2 days after moderately emetogenic treatment is completed.

•Treatment-appropriate antiemetic prophylaxis should precede each emetogenic treatment and proceed on a fixed schedule. Patients should not be expected to recognize symptom prodromes and to rely on unscheduled (i.e., as needed) antiemetics.

•Antiemetics should be given at the lowest effective doses.

•Patients’ responses to antiemetic prophylaxis and treatment should be monitored and documented with standardized validated tools.

•Healthcare providers historically underestimate the incidence and severity of emetic symptoms, particularly nausea.

•Patient input is essential to capture information about

οEvents that healthcare providers cannot observe due to patient location and the subjective nature of nausea.

οConditions and interventions that modulate a patient’s emetic symptoms.

•The MASCC has developed and makes available online a standardized eight-item questionnaire that can be used to document the number of vomiting episodes and the number and severity of episodes of nausea both acutely and within the 4 days (24 to 120 hours) after emetogenic treatment.

οThe MASCC Antiemesis Tool (MAT), a guide for using the tool, and an outcomes score sheet are available in 12 languages in digital formats for downloading, and in an application for handheld devices.

οInformation about gaining approval for using the MAT is available online at www.mascc.org

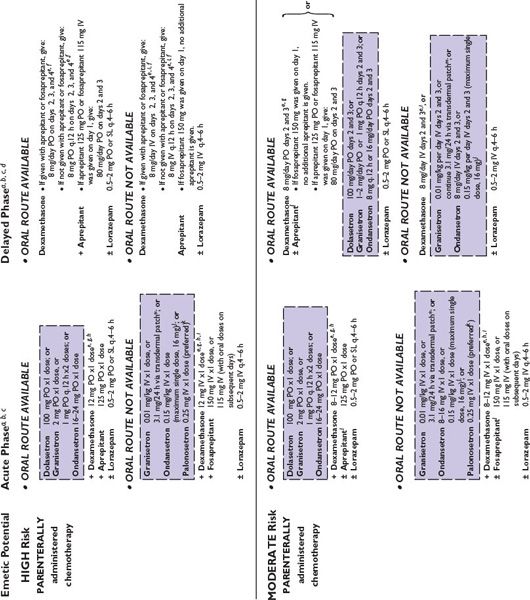

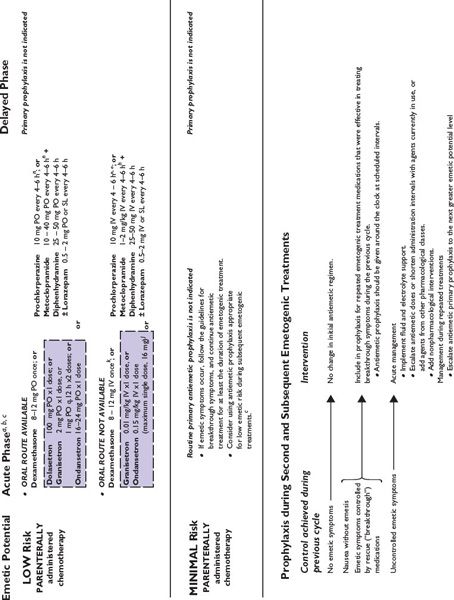

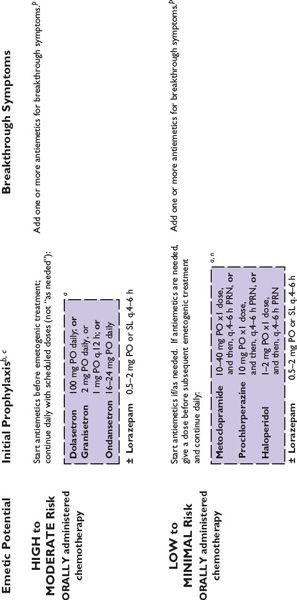

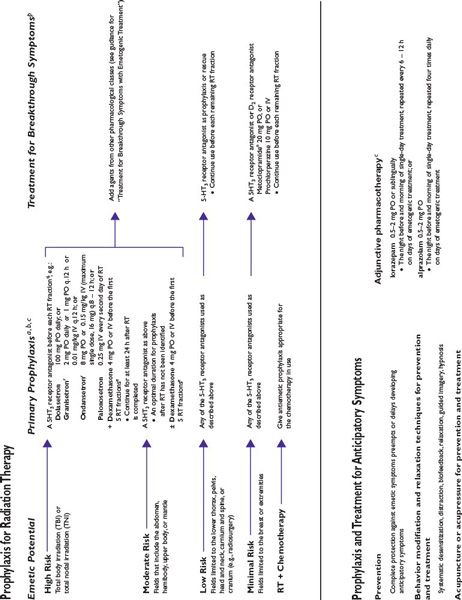

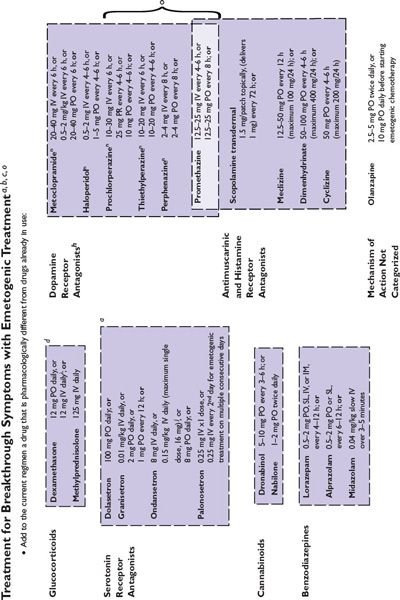

Figure 38.2 integrates evidence-based guidelines for treatment-appropriate antiemetic prophylaxis recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer and European Society for Medical Oncology, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the consensus of experts in oncology. Recommendations are based on assessment of emetic risk and generally apply to adult patients, but may not be appropriate in all clinical situations. Drug selection and utilization should be tempered by professional judgment, including an assessment of patient-specific risk factors and circumstances, and recognition of available resources.

Clinicians may expect to encounter a minority of patients who do not respond to treatment-appropriate antiemetic prophylaxis recommended by oncology specialty organizations’ guidelines. Suboptimal antiemetic prophylaxis places patients at risk for breakthrough and refractory emetic symptoms and debilitating morbidity, which may adversely affect their safety, comfort, and quality of life, and complicate their care.

For patients who respond suboptimally to initial antiemetic prophylaxis, reevaluate factors that may cause or contribute to emetic symptoms, and those that may compromise the effectiveness of pharmacologic prophylaxis, including

■The emetogenic risk associated with treatment.

•The appropriateness of initial antiemetic prophylaxis for the emetogenic challenge presented by treatment

•Selection of drugs, doses/dosages, and administration routes and schedules for use

■Healthcare provider adherence in prescribing and patient compliance in using planned antiemetic prophylaxis.

■Disease status.

■Comorbid conditions (electrolyte abnormalities, renal failure, sepsis, constipation, tumor infiltrating or obstructing the GI tract, intracranial disease).

■Whether concomitantly administered medications may potentially compromise the effectiveness of the antiemetics utilized by including additional emetogenic medications or through pharmacokinetic interactions.

Empiric secondary prophylaxis and treatment for patients who demonstrate suboptimal antiemetic control should follow a rational approach. Pharmacologic interventions typically include drugs presumed to mediate antiemetic effects through an interaction with one or more neurotransmitter receptors implicated in either provoking or mitigating emesis, and through mechanisms not addressed by medications already in use. Unfortunately, drugs used empirically often are less safe at effective or clinically useful doses and schedules (e.g., dopaminergic and cannabinoid receptor antagonists) than agents recommended for primary prophylaxis. Whether used adjunctively or as replacement for initial prophylaxis, second-line alternatives may increase treatment costs and the risks of overtreatment and adverse effects.

BREAKTHROUGH SYMPTOMS

Primary antiemetic prophylaxis recommended by oncology specialty organizations’ guidelines are associated with complete control (no emesis) during the acute phase in ≥80% of patients who receive highly emetogenic treatments and even greater complete control rates in the setting of moderately emetogenic treatment; however, more than 50% of patients who receive moderately or highly emetogenic therapy still may experience delayed or breakthrough nausea or emesis in spite of good control achieved acutely. In general, it is more difficult to arrest emetic symptoms after they develop than it is to prevent them from occurring. Breakthrough symptoms require rapid intervention. All patients who receive moderately or highly emetogenic treatment should from the outset of treatment have access to antiemetic medications for treating breakthrough symptoms, whether through orders for treatment during a visit or admission to a healthcare facility or, for outpatients, a supply of antiemetic medication and clear instructions about how to use it in supplementing or modifying their initial antiemetic regimen. If needed and once begun, breakthrough treatment should be administered at scheduled intervals and continued at least until after emetogenic treatment is completed and symptoms abate.

In general, nausea may still occur and often is more prevalent than vomiting even in patients who achieve overall good or better emetic control.

Suboptimal Control

Suboptimal control of emetic symptoms with antiemetic prophylaxis raises the following questions:

■Was the prophylactic strategy given an adequate trial (time of initiation relative to the start of emetogenic treatment and duration of use)?

■Were the antiemetics selected and the doses and administration schedules prescribed appropriate for the emetogenic challenge?

■Did the patient understand and comply with instructions for antiemetic use?

■Would increased doses or shorter administration intervals improve antiemetic effectiveness without causing or exacerbating adverse effects associated with the antiemetics utilized?

Rescue Interventions

If it becomes necessary to “rescue” a patient from a suboptimal response:

■Assess a symptomatic patient’s state of hydration and serum/plasma electrolytes for abnormal results.

•Replace fluids and electrolytes as needed.

■Add antiemetic agents that act through mechanisms different from antiemetics already in use.

•It may be necessary to use more than one additional drug to establish antiemetic control.

■Give scheduled doses around the clock at least until emetogenic treatment is completed, and at doses and on a schedule appropriate for the medication.

•Do not rely on as needed administration to achieve or maintain control of emetic symptoms.

■Consider replacing ineffective drugs with a more potent or longer-acting agent from the same pharmacologic class.

■Consider replacing an antiemetic medication that requires ingestion and absorption from the GI tract or percutaneous absorption with the same or a different drug administered by an alternative administration route (disintegrating tablets and soluble films for oral administration, injectable formulations).

•Emetic symptoms may impair GI motility and drug absorption from the gut.

•Some patients may be too ill to swallow and retain oral medications.

•Rectal suppositories are a practical alternative for patients who cannot ingest medications, but the rate and extent of absorption varies among drugs and patients.

•Clinicians should query and ascertain patients’ willingness to comply with rectal administration.

•Sustained- and extended-release formulations (oral and transdermal products) should not be used to initially bring ongoing symptoms under control.

■Replace drugs associated with unacceptable adverse effects with one or more drugs from the same or a different pharmacologic class without potential for the same toxicity, or for which particular adverse effects are less likely to occur.

These strategies may be utilized during cyclical treatment or to intervene when response to prophylaxis is unsatisfactory.

FIGURE 38.2 Algorithms for antiemetic prophylaxis and treatment for parenterally and orally administered emetogenic drugs. 5-HT3, serotonin (5-HT3 subtype); ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; D2, dopamine (D2 subtype); IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; MASCC/ESMO, Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/European Society for Medical Oncology; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network®; PO, oral; PR, rectal; RT, radiation therapy; SL, sublingual. aMedications are not listed in order of preference except where indicated. Pharmacologically similar alternatives are circumscribed by a broken line. bOral prophylaxis should begin 1 hour before commencing cytotoxic treatment. IV prophylaxis may be given minutes before emetogenic treatment. cAntiemetic prophylaxis should be repeated each day emetogenic treatment is administered. dDelayed-phase prophylaxis may begin 12 to 24 hours after the start of emetogenic treatment. eConsider administering a histamine (H2 subtype) receptor antagonist (other than cimetidine) or a proton pump inhibitor concurrently with dexamethasone to prevent GI irritation. f The recommended schedule for dexamethasone is twice daily if used without aprepitant and once daily if used with aprepitant. gIncrease dexamethasone dose to 20 mg if it is given without aprepitant or fosaprepitant. hDexamethasone 12 mg is the only dexamethasone dose tested in combination with aprepitant in large randomized trials. i When administered IV, dexamethasone should be given as a short infusion over 10 to 15 minutes to prevent uncomfortable sensations of warmth. jProduct labeling for ondansetron approved by the FDA recommends single intravenously administered doses should not exceed 16 mg. kMASCC/ESMO guidelines recommend combination antiemetic prophylaxis with dexamethasone and palonosetron for all chemotherapy with moderate emetic risk, including chemotherapy regimens containing an anthracycline and cyclophosphamide (an “AC” regimen) when an NK1 receptor antagonist cannot be used in combination with dexamethasone and a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. NCCN Guidelines® recommend palonosetron as the preferred 5-HT3 receptor antagonist antiemetic in combination with dexamethasone for antiemetic prophylaxis for patients who receive intravenous chemotherapy with high or moderate emetogenic risk. l NCCN Guidelines recommend adding aprepitant in primary antiemetic prophylaxis for selected antineoplastics when those medications are given at dosages associated with moderate emetogenic risk, including carboplatin, cisplatin, doxorubicin, epirubicin, ifosfamide, irinotecan, or methotrexate. mGranisetron Transdermal System (Sancuso®; ProStraken Inc., Bedminster, NJ), an adhesive-backed patch, contains 34.3 mg granisetron and delivers an average daily dose of 3.1 mg. nGenerally, regimens containing D2 receptor antagonists and metoclopramide doses ≥20 mg should include primary prophylaxis with anticholinergic agents against acute dystonic extrapyramidal reactions, for example, diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO or IV every 6 hours. Benztropine and trihexyphenidyl are alternatives. Parenteral administration is preferred for prompt treatment of extrapyramidal symptoms, as well as interrupting or discontinuing the drug which provoked the adverse reaction. oWhen administered IV, phenothiazines should be given over 30 minutes to prevent hypotension. pMedications identified for breakthrough symptoms should be added to a patient’s primary antiemetic prophylaxis regimen without replacing drugs used in primary prophylaxis unless drugs used to treat breakthrough symptoms duplicate mechanistically those used in primary prophylaxis or a patient has experienced unacceptable adverse effects attributable to a component of primary prophylaxis. qContinue for at least 24 hours after completion of radiation treatment. rASCO guideline update (2011) identifies granisetron and ondansetron as the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists preferred in prophylaxis against radiation-induced emetic symptoms.

Secondary Antiemetic Prophylaxis and Treatment

When antiemetic treatment is needed for breakthrough symptoms, reevaluate the prophylactic regimen that failed to provide adequate antiemetic control before repeating cycles of emetogenic treatment. Consider alternative antiemetic prophylaxis strategies during subsequent emetogenic treatments, including:

■Consider escalating antiemetic prophylaxis to a regimen appropriate for the next greater level of emetic risk.

■Add additional scheduled antiemetics at appropriate doses and administration intervals.

•Consider drugs that proved of value in controlling breakthrough symptoms or another drug that acts through the same pharmacologic mechanism.

■For regimens that included a 5-HT3 antagonist, consider switching to a different 5-HT3 antagonist.

•There is evidence, albeit meager, that suggests all patients may not achieve the same measure of antiemetic control with all 5-HT3 antagonists.

■Consider adding an anxiolytic drug to the patient’s regimen.

■Consider adding aprepitant to antiemetic prophylaxis if its potential for pharmacokinetic interactions will not adversely affect concomitantly administered medications.

■If alternative treatment for a patient’s neoplastic disease exists, consider a different regimen with which similar therapeutic benefit may be achieved without greater adverse outcomes.

•Perhaps worth considering only if the goal of treatment is not curative.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC INTERVENTIONS

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree