FIGURE 35.1 Approach to patients with fever and neutropenia without clinically or microbiologically documented infection. The choice between piperacillin–tazobactam (shown here emphasizing the higher dose required in neutropenic patients), cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, and ceftazidime will vary between institutions based on local resistance patterns. For specific infections, see the text and Table 35.1. * This antibacterial regimen for the neutropenic patient with sepsis will vary between institutions, depending on the local patterns of antibiotic resistance. Carbapenem + fluoroquinolone (or aminoglycoside or colistin) + vancomycin (or daptomycin or linezolid) + echinocandin is typical. We prefer meropenem and daptomycin because both can be “pushed” intravenously in a few minutes. The antifungal of choice will vary depending on previous antifungal prophylaxis. †The empirical gram-positive coverage should usually be discontinued after 48 to 72 hours if there is no bacteriologic documentation of a pathogen requiring its use, except in soft tissue or tunnel infections. Linezolid or daptomycin may be substituted for vancomycin if there is suspicion or high endemicity of VRE. For a detailed discussion of antifungal therapy options, as well as for the role of oral antibiotics in low-risk patients, see the text. AmB, amphotericin B; MRSA, methicillin (oxacillin)-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PRSP, penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae.

EVALUATION

■History and physical examination should be performed with special attention to potential sites of infection: skin, mouth, perianal region, and intravenous catheter exit site.

■Routine complete blood count with differential, chemistries, including liver enzymes and creatinine, urinalysis, blood and urine cultures, and chest x-ray should be obtained.

■Blood cultures: Two sets of blood cultures are more sensitive than a single set for the diagnosis of bacteremia. To determine if a bacteremic episode is related to the catheter, it is advisable to draw blood from the intravenous catheter and a peripheral vein. A differential time to positivity of 2 hours or more (i.e., the cultures obtained from the catheter become positive earlier than the peripheral stick) has good predictive value for catheter-related bacteremia.

■Any accessible sites of possible infection should be sampled for gram stain and culture (catheter site, sputum, etc.).

■Ideally, blood cultures should be obtained prior to starting antibiotics, but failure to do so should not delay antibiotic administration.

EMPIRICAL ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

■A summary of the initial management of the patient with fever and neutropenia and no localizing signs or symptoms is provided in Figure 35.1.

■The goal of treatment is to provide broad antibiotic coverage with minimal toxicity.

■Most bacterial infections during neutropenia are caused by microorganisms that colonize the oral mucosa, the bowel, and the skin of the patient. P. aeruginosa is particularly prevalent during neutropenia. Due to their potential for faster progression and higher morbidity, the emphasis is on coverage of enteric gram-negative bacilli and Pseudomonas. This may be achieved by using single agents or by combining several antibiotics.

Monotherapy

■Monotherapy with selected broad-spectrum β-lactams with activity against P. aeruginosa is as effective as combination antibiotic regimens (β-lactam plus aminoglycoside) for empirical therapy of uncomplicated fever and neutropenia, and has less toxicity. The following regimens are the options recommended by the 2011 guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA):

•Cefepime, 2 g IV every 8 hours

•Imipenem–cilastatin, 500 mg IV every 6 hours

•Meropenem, 1 g IV every 8 hours

•Piperacillin–tazobactam, 4.5 g IV every 6 hours

■The choice of one agent over another should be guided mainly by institutional susceptibilities, which may make one or more of the aforementioned agents a poor choice. Some institutions may still find ceftazidime (which is not on the IDSA’s list anymore), 2 g IV every 8 hours, perfectly adequate. By meta-analysis, all these agents seem to offer similar efficacy, but carbapenems may be associated with increased risk of Clostridium difficile colitis.

Combination Therapy with Expanded Gram-Negative Coverage

■Combination therapy aiming to broaden the anti–gram-negative activity may be used empirically in certain clinical circumstances, although there are no definitive data showing clinical benefit. Combination therapy should be used in cases of

•Severe sepsis or septic shock

•High prevalence of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli

■Effective antibiotic combinations include one of the aforementioned β-lactams plus an aminoglycoside (choice based on local resistance) or colistin. Ciprofloxacin may be used instead of an aminoglycoside if the prevalence of quinolone-resistant bacteria is low or in patients at high risk of aminoglycoside toxicity. Colistin and polymixin B are being used more frequently with the increasing prevalence of KPC and multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii.

Role of Vancomycin and Other Agents with Gram-Positive Coverage

Vancomycin should be part of the initial empirical regimen under the following circumstances:

■Severe sepsis or septic shock

■Pneumonia

■Soft tissue infection (cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis)

■Clinically suspected catheter-related infections (not the mere presence of an intravascular device)

■Severe mucositis or other risk factors for infection with Streptococcus mitis (use of prophylaxis with fluoroquinolones, high-dose Ara-C, use of H2 blockers)

■Known colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (PRSP)

Addition of vancomycin to the initial regimen:

■Adding vancomycin to the initial regimen because of persistent fever alone does not improve the outcome and is not recommended.

■Positive blood cultures for gram-positive bacteria are an indication for the addition of agents with gram-positive activity.

■Pending identification, the choice between vancomycin, linezolid, and daptomycin should be informed by the local prevalence of VRE and preliminary morphologic information from the gram stain (gram-positive cocci in pairs and short chains suggest enterococcus or S. pneumoniae, gram-positive cocci in clusters suggest Staphylococcus).

■It is not known at this time whether linezolid or daptomycin should be used empirically in patients known to be colonized with VRE, nor whether screening cultures result in improved outcomes.

■In the case of documented VRE infection, the choice between daptomycin, linezolid, and quinupristn–dalfopristin is not based on clinical outcome data, but on theoretical considerations and local resistance patterns.

Oral Therapy

■Empirical oral antibiotics may be acceptable for neutropenic patients who are not at high risk of severe morbidity or death.

■High-risk patients are those who received chemotherapy associated with prolonged and profound neutropenia (e.g., AML induction therapy), as well as patients with symptoms or signs of clinical instability or with significant comorbidities (e.g., COPD, heart failure). Low-risk patients do not exhibit any high-risk factors and their neutropenia is expected to be short lived. These patients could be considered for outpatient antibiotic treatment.

■A quantitative risk assessment, the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) scoring system, has been validated. Points are allocated for burden of illness (no or mild symptoms 5, severe symptoms 3), absence of hypotension (5), no chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (4), solid tumor or no previous fungal infection (4), absence of dehydration (3), outpatient status (3), and age <60 years (2) and the points are added up. Patients with a score of ≥21 points (of 26 possible) are at “low risk,” and can be considered for oral therapy.

■The two recommended oral regimens are

•Ciprofloxacin, 750 mg PO every 12 hours, plus amoxicillin/clavulanate, 875 mg (amoxicillin component) PO every 12 hours

•Ciprofloxacin, 750 mg PO every 12 hours, plus clindamycin 450 mg PO every 6 hours

We recommend starting oral antibiotics on an inpatient basis, and then consider discharge after 24 hours of observation and documentation that the blood cultures remain negative. Following discharge, patients should be seen daily and instructed to call or come in to clinic for new or worsening symptoms or persistent high fever. Approximately 20% of patients will need readmission to the hospital (factors associated with need for admission: >70 years old, poor performance, ANC <100/mm3).

Low-risk patients with no documented infection who respond to empirical IV antibiotics can be switched to oral antibiotics until their neutropenia resolves based on clinical judgment. We recommend observing these patients on oral therapy as inpatients for at least 24 hours before discharge.

Modifications of the Initial Antibiotic Regimen

■After patients are started on empirical antibiotics for fever and neutropenia, their course must be monitored closely for development of new signs or symptoms of infection; antibiotic therapy should be modified based on clinical findings.

■Therapy modification is necessary in 30% to 50% of cases during the course of neutropenia.

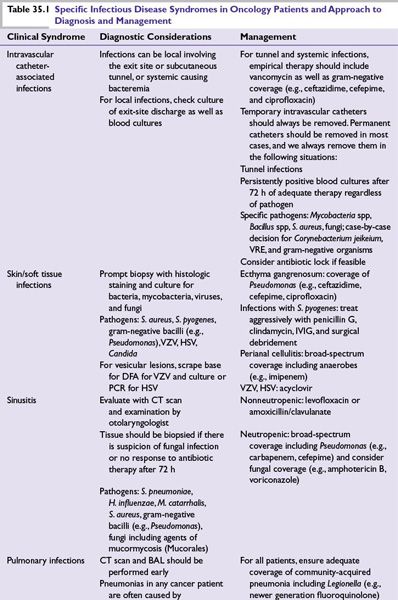

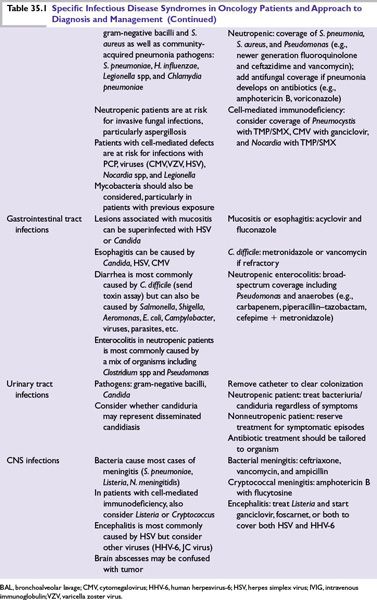

■Specific modifications are dictated by specific clinical syndromes (Table 35.1) or by microbiologic isolates.

■Persistent fever with no other clinical findings is not an indication for modification of the antibacterial regimen.

■If there is no documented gram-positive infection, gram-positive coverage may be stopped if it had been initiated.

■After 4 to 7 days of persistent fever, it is accepted practice to start some antifungal agent.

■In the case of recrudescent fever the antibacterial and antifungal agents should be changed and imaging studies performed.

Empirical Antifungal Therapy

Candida and Aspergillus infections are most common and increase in frequency with increased duration of neutropenia. An antifungal agent should be added empirically for neutropenic patients in the following circumstances:

■Severe sepsis or septic shock: it may be caused by Candida; amphotericin or an echinocandin should be added.

■Persistent fever after 4 to 7 days of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy.

■Recrudescent fever.

■Candida colonization: candiduria, thrush.

Treatment options include

■Amphotericin B deoxycholate, 0.6 to 1 mg/kg/day IV.

■A lipid formulation of amphotericin B such as liposomal amphotericin B (Ambisome) or amphotericin B lipid complex (Abelcet), 3 to 5 mg/kg/day IV.

■Voriconazole, 6 mg/kg IV every 12 hours for 24 hours followed by 4 mg/kg IV every 12 hours.

■Caspofungin, 70 mg IV loading dose followed by 50 mg IV daily.

For persistent fever, these four options are well validated as empirical additions. Of note, an effort should be made to rule out the presence of active invasive fungal infection by performing a thorough physical examination and obtaining CT studies as clinically indicated. Some authorities have suggested to start antifungal agents only when there is ancillary evidence of fungal infection besides the fever (e.g., positive serologic tests like galactomannan and/or ß-D-glucan). The role of this so-called “preemptive” antifungal therapy as opposed to the traditional “empirical” addition of antifungal agents in persistent fever has not been clearly defined.

It should be noted that posaconazole (a new broad-spectrum antifungal agent given as 200 mg PO every 8 hours with food) has shown very good activity as antifungal prophylaxis, but has no role in the acute management of presumptive fungal infection, because therapeutic levels are not achieved for 5 to 7 days after starting.

Duration of Antibiotic Therapy

■Documented bacterial infection: Antibiotics should be continued for the amount of time standard for that infection or until resolution of neutropenia, whichever is longer.

■Uncomplicated fever and neutropenia of uncertain etiology: Antibiotics should be continued until the fever has resolved and the ANC is above 500 for 24 hours.

■If no infection was documented and the patient became afebrile on antibiotics, but the neutropenia persists, it is acceptable to complete 2 weeks of treatment. At that point one may discontinue the antibiotics and observe. Alternatively, it is acceptable to resume fluoroquinolone prophylaxis until marrow recovery.

■If there is no documented fungal infection, antifungal agents can also be discontinued at the time of resolution of neutropenia.

FEVER IN THE NONNEUTROPENIC CANCER PATIENT

■Noninfectious causes of fever in cancer patients include, among others, the underlying malignancy, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, medications, blood products, and, in allogeneic stem cell transplant, graft-versus-host disease.

■Infections, however, are common in patients with all types of malignancies in all stages of treatment. In addition to neutropenia, there are several other factors that contribute to increased susceptibility to infection and should be considered when trying to diagnose an episode of fever and formulate a treatment plan.

•Local factors: Breakdown of barriers (mucositis, surgery) that provide a portal of entry for bacteria; obstruction (biliary, ureteral, bronchial) that facilitates local infection (cholangitis, pyelonephritis, postobstructive pneumonia).

•Intravascular devices, drainage tubes, or stents may become colonized and lead to local infection, bacteremia, or fungemia.

•Splenectomy increases susceptibility to infection due to S. pneumoniae and other encapsulated bacteria.

•Deficiencies of humoral immunity (multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia) lead to increased susceptibility to encapsulated organisms such as S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae.

•Defects in cell-mediated immunity (lymphoma, hairy cell leukemia, treatment with steroids, fludarabine, and other drugs, hematopoietic stem cell transplant [HSCT]) increase susceptibility to opportunistic infections caused by Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacteria, Cryptococcus neoformans, Pneumocystis jirovecii, cytomegalovirus (CMV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), and other pathogens.

Antibiotic Therapy in the Nonneutropenic Cancer Patient

■Antibiotics should be administered empirically in the setting of fever only when a bacterial infection is considered likely.

■Ideally one should formulate a “working hypothesis” as a fundamental basis to choose the appropriate regimen, for example, pneumonia, cholecystitis, and urinary tract infection would likely require different antibiotics.

■In the absence of localizing signs and symptoms, consider bacteremia, particularly in patients with intravascular devices. Many authorities recommend empirical antibiotics (levofloxacin, ceftriaxone) until bacteremia is ruled out.

■Clinically documented infections and sepsis should be treated with antibiotics as warranted by the clinical scenario.

■Whenever antibiotics are started, a plan with specific endpoints should be formulated to avoid unnecessary toxicity, superinfection, and development of resistance.

SPECIFIC INFECTIOUS DISEASE SYNDROMES

If a patient presents with clinical signs and symptoms of a specific infection, with or without neutropenia, the workup and therapy are guided by the clinical suspicion (see Table 35.1).

Bacteremia/Fungemia

■A positive blood culture should prompt immediate initiation of appropriate antibiotics in a neutropenic patient or in a nonneutropenic patient who is febrile or clinically unstable.

■If the isolated organism is one that is commonly pathogenic, such as S. aureus or gram-negative bacilli, antibiotics should be started even if the patient is afebrile and clinically stable.

■If the isolate is a common contaminant, such as a coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, and the patient is afebrile, clinically stable, and nonneutropenic, it may be appropriate to repeat the cultures and observe before starting antibiotics.

■In every case of bacteremia, follow-up blood cultures should be obtained to document the effectiveness of therapy, and the source of the infection should be sought.

Gram-Positive Bacteremia

Gram-Positive Cocci

■Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species is the most common cause of bacteremia. The intravenous catheter is usually the source. In the setting of neutropenia or clinical instability, the patient should be treated with vancomycin.

■S. aureus bacteremia is associated with a high likelihood of metastatic complications if not treated adequately. Intravascular devices should be removed. Complicated S. aureus bacteremia (persistently positive blood cultures, prolonged fever, metastatic infection, and endocarditis) requires 4 to 6 weeks of treatment. Many authorities recommend that transesophageal echocardiogram should be performed in every case to rule out endocarditis.

■Oxacillin and nafcillin are the drugs of choice for treating methicillin-susceptible S. aureus; vancomycin should be reserved for MRSA or the treatment of penicillin-allergic patients. Daptomycin may also be an alternative as long as there is no pulmonary involvement.

■Bacteremia with viridans group streptococci may cause overwhelming infection with sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in the neutropenic patient; vancomycin therapy should be used until susceptibility results are known (most, but not all, isolates are susceptible to ceftriaxone and carbapenems).

■Risk factors for viridans group streptococci bacteremia include severe mucositis (particularly following treatment with cytarabine), active oral infection, and prophylaxis with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) or a fluoroquinolone.

■Enterococci often cause bacteremia in debilitated patients who have had prolonged hospitalization and have been on broad-spectrum antibiotics.

■VRE are an increasingly common cause of bacteremia and should be treated with linezolid (600 mg every 12 hours IV), daptomycin (6 mg/kg every 12 hours IV), or quinupristin–dalfopristin (7.5 mg/kg every 8 hours IV). There is no evidence at this time whether empirical treatment with these agents should be initiated in febrile neutropenic patients with known VRE colonization.

Gram-Positive Bacilli

■Clostridium septicum is associated with sepsis and metastatic myonecrosis during neutropenia. Treat with high-dose penicillin or a carbapenem.

■Listeria monocytogenes may cause bacteremia with or without encephalitis/meningitis in patients with defects in cell-mediated immunity. Ampicillin plus gentamicin is the treatment of choice. TMP/SMX can be used in penicillin-allergic patients.

■Other gram-positive bacilli such as Bacillus, Corynebacterium, and Lactobacillus species are common contaminants of blood cultures, but in the setting of neutropenia can cause true infection that is usually catheter related. Propionibacterium is almost always a contaminant, but it can cause infection of Ommaya reservoirs.

Gram-Negative Bacteremia

■Gram-negative bacteria in the blood should never be considered contaminants and should be treated immediately.

■Depending on the preliminary result from the Microbiology lab (variable from one laboratory to another), preliminary information may be nonexistent or may be specific enough (e.g., “enteric-like” or “Pseudomonas-like” gram-negative bacillus, to guide antibiotic choice), it may be safer to initiate therapy with two antimicrobials to ensure adequate coverage until susceptibility results are available. Combination therapy offers no convincing benefit once susceptibilities are known.

■Escherichia coli and Klebsiella

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree