TREATMENT

In the past treatment options for CML included conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy with hydroxyurea

and busulfan, interferon α, with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation being the only potentially curative option. In the last decade tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have revolutionized the treatment of CML as well as changing treatment algorithms, treatment goals, monitoring tools, and the expectations of patients and physicians. The mainstay of CML therapy is now IM, and second-generation TKIs such as nilotinib and dasatinib, and more recently ponatinib. These newer agents can overcome genetic mutations that previously caused TKI resistance as well as lead to quicker and deeper molecular remission when compared to IM.4 Omacetaxine, a subcutaneously bioavailable semisynthetic form of homoharringtonine, was recently approved for treatment in TKI-resistant patients.

Hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea is a cytotoxic antiproliferative agent that is administered orally and is used when a patient has an elevated white blood cell count (>80 × 109/L) to allow rapid control of blood counts. It induces hematologic responses in 50% to 80% of patients and is continued until confirmation of diagnosis; however, it does not alter disease course. Allopurinol may be added to prevent tumor lysis syndrome when starting hydroxyurea.

Interferon

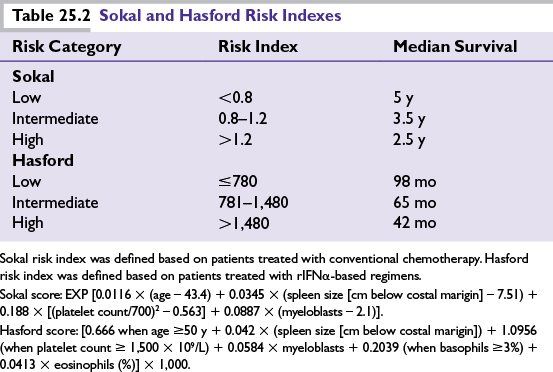

Recombinant IFNα-based regimens were the standard therapy for chronic-phase CML before the discovery of IM, and while effective and even curative in some patients, they had significant adverse effects that greatly impaired quality of life and adherence to treatment. Follow-up for large studies of rIFNα showed 9- or 10-year OS between 27% and 53%.

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Imatinib Mesylate

With the advent of IM, CML set the bar for how malignancy could be effectively treated with targeted therapy, and ushered in a new era of research in this field. IM is a phenylaminopyrimidine derivative that inhibits the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase by competitive binding at the ATP-binding site. Although active in all phases of CML, the most durable responses are seen in newly diagnosed patients in CP. Results of the pivotal IRIS trial established the superiority of IM, and at 8-year follow-up, the estimated EFS was 81%, freedom from progression to CML-AP or CML-BP 92%, and OS 85%. When only CML-related deaths were considered, OS reached 93%. An estimated 7% of patients progressed to accelerated-phase CML or blast crisis. As a result, IM 400 mg daily was established as the standard of care for patients with newly diagnosed chronic-phase CML. The most common adverse events seen with IM are skin rash, muscle cramps, myelosuppression, diarrhea, and liver function test abnormalities.

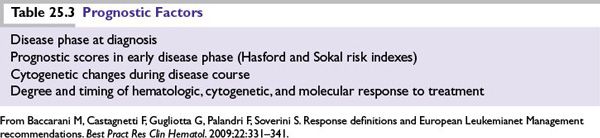

The high rate of complete cytogenetic response with IM has shifted the goal of therapy to achieving molecular responses measured by PCR. Response criteria are summarized in Table 25.4. Duration of remission and survival are related to the depth of clinical response achieved. As more information has become available, the responses to TKI therapy have become the most important marker of overall prognosis. This makes molecular monitoring an essential component of CML management. More recently monitoring schema have become available that help to determine when a second-generation TKI would be appropriate as well as timing to refer for allogeneic stem cell transplant. If there is suboptimal response to IM, then the options remaining are to increase IM dose, change to a second-generation TKI, or proceed to allogeneic transplant. At this time there are no data favoring one option over another although the failure of IM predicts for poorer prognosis. Most experts would refer patients for stem cell transplant evaluation after suboptimal response to 2 TKIs. The response schema proposed by Baccarani et al. is summarized in Table 25.5.

Second-Generation Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree