Midline Catheters

One subclass of peripheral angiocatheters is the midline catheter. Midline catheters are PICCs. They are usually inserted into the antecubital fossa or into the brachial veins with the guidance of a handheld ultrasound device. The catheter is then advanced 8″ to 10″, just proximal to the axillary line. In this position, the catheter is not considered central and should be treated as a peripheral angiocatheter with regard to infusates. However, since the catheter tip is in a larger vessel with increased blood flow, the risk of phlebitis and infiltration is decreased as compared to peripheral angiocatheters. Typical dwell time for midline catheters is 1 to 2 weeks with careful monitoring for complications.3 In addition to extended dwell time, the midline catheter, unlike the PICC, does not need radiographic verification for tip placement, since it is not advanced centrally. This benefit yields less costly insertion fees and simplification of insertion-related malpositioning. Phlebitis and thrombosis are also less likely to occur when compared to central venous lines. Midlines are particularly beneficial in patients who would otherwise require serial placements and replacements of short PIVs and do not need the long-term access or central venous dwell of a PICC line. Midline catheters can also be used in the setting of a relative contraindication to PICC access such as in patients with end-stage renal disease where the central veins should be accessed as minimally as possible.

Midline catheters do have limitations. First, their tips do not reside centrally so infusates are limited to those that are safe for PIVs. Since the axillary vein lies deep in the axillary region, it may be difficult to identify early phlebitis, infiltration, or infection. Frequently, a blood return is not achieved for confirmation of vascular patency or specimen collection. The short intravenous catheter length compared to the external component yields increased risk of dislodgement. Midline catheters require daily flushing to maintain patency and dressing changes at least weekly, which may require home health services. Moreover, catheter-related bloodstream infection rates are similar to those of PICCs.

Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter

The peripherally inserted central venous catheter (CVC) was first described in 1975 by Hoshal in a case series in which he described using a 61 cm silicone catheter that was threaded to the superior vena cava (SVC) through the basilic or cephalic veins. The series demonstrated successful application of the concept in the implementation of total parenteral nutrition with 30 of 36 catheters lasting the entire duration of treatment (up to 56 days).

A PICC is a long, flexible catheter that is inserted into a peripheral vein and advanced into the central circulation. It is typically placed in a vein of the upper arm, although it can also be introduced in the internal or external jugular veins, the long or short saphenous veins, the temporal vein, or the posterior auricular veins. The saphenous vein, temporal vein, and posterior auricular veins are usually reserved for pediatric patients. Once the vein is cannulated, the catheter is digitally advanced until its distal tip resides in the SVC or the IVC. There is minimal risk to chest organs as compared to catheters placed directly in the central venous system. The tip location of the PICC is desired in the lower third of the SVC, preferably at the junction of the right atrium with either the SVC. The external component is secured to skin, preferably with a removable locking device or sutures.

PICCs come in single, double, or triple lumens in a variety of sizes. The catheters have a small outer diameter allowing for initial insertion into smaller vessels prior to advancement centrally and are radio-opaque for visualization of catheter tip placement on chest radiograph. These devices can be modified in length, specific to each patient. Some PICCs are approved for use with power injectors that can rapidly administer a radiologic contrast bolus. Insertion can be done during inpatient hospitalization, outpatient settings, and in the home by certified nurses.

PICCs are used for patients with poor venous access that need infusions of solutions with extreme pH or osmolarity, extended intravenous medications use (1 week to several months in duration), intermittent blood sampling, and as a respite from long-term catheters. For these purposes, PICCs are associated with greater ease and safety with insertion when compared with conventional CVCs. Moreover, PICCs also help minimize the pain associated with repeated venipuncture whether for replacement IVs or lab draws. Power-injectable PICCs may be utilized in patients where frequent contrasted imaging studies are likely.

The relatively small lumen and long length result in decreased flow rates, especially with infusions of viscous solutions such as blood products or intravenous nutrition therapy and often cannot be used for gravity-driven infusions when pumps are unavailable such as in home settings. Due to their small caliber, these lines are not considered adequate intravenous access for resuscitation in the setting of hemodynamic compromise. Frequent flushing of the catheter with normal saline and/or heparin lock, and dressing changes weekly or more frequently may be challenging for some patients. In addition, careful attention is required to protect the exposed catheter exit site from contamination or damage. The patient’s modesty may be compromised due to visibility of the external component. There are activity limitations including no straining maneuvers such as heavy lifting or straining that could alter the intrathoracic pressure that could lead to catheter malposition. Malpositioning can even occur with physiologic pressure changes during cough or forceful emesis. Submersion of the extremity in water when bathing in pools or hot tubs during catheter dwell is forbidden secondary to infection risks. Patients may not be candidates for PICCs if they have had surgical alteration of anatomy, lymphedema, ipsilateral radiation to the chest or arm, or loss of skin integrity at the anticipated insertion site, or anticipate future dialysis access needs.

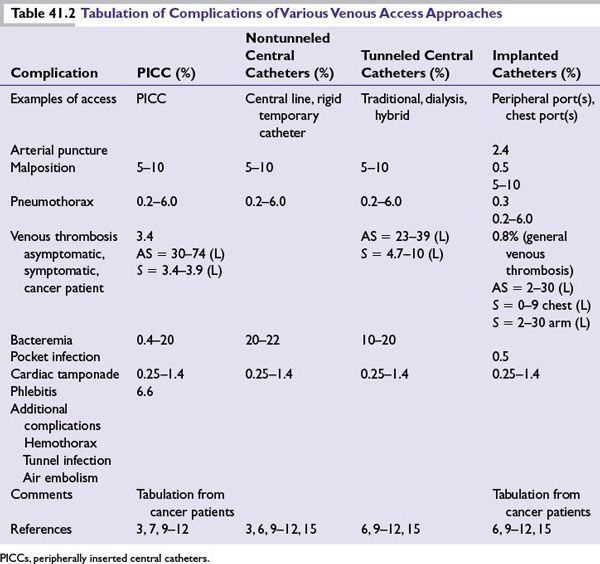

However minimal, PICC-related complications should be recognized. These include infection, phlebitis, vein thrombosis, catheter occlusion, catheter breakage/leaking, and inadvertent removal prior to completion of therapy (Table 41.2). Oncology patients are at increased risk for venous thrombus formation secondary to their malignancy, treatment regimen, and the trauma of catheter insertion.8 Improper final tip positioning and subclavian access as opposed internal jugular access may also contribute to thrombosis.9,10 In cancer patients, PICCs have been shown to have less incidence of deep venous thrombosis than tunneled catheters used for the same purpose.

Percutaneous Central Venous Catheters

Aubaniac was the first to describe cannulation of a central vein (the subclavian) for venous access.11 These CVCs, either the thin flexible or the larger rigid variety, are inserted directly into the central circulation via the subclavian vein, the external jugular vein, the internal jugular vein, or the femoral vein. Catheters included in this category include the standard CVCs or temporary rigid hemodialysis/apheresis catheters. The CVC is utilized in the hospital setting for acute central venous access with a dwell time of up to 14 days. CVCs are typically used for rapid infusion, multiple infusates needed simultaneously, or hemodynamic monitoring (central venous pressure measurement). Thus, CVCs are for use in acute care settings, thus reserving them for hospitalized patients only.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree