Radiation

■In patients with unresectable tumors, available data suggest that tumor control is rarely achieved with RT.

■A number of reports have documented improvements in survival rates in cases of intraoperative or postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy. No prospective randomized controlled trials have been performed to address this issue. In 2003, however, Jarnigan and colleagues found that only 15% of patients had locoregional recurrence as their only site of recurrent disease which highlights the importance of effective, adjuvant systemic strategies.

Chemotherapy and Palliation

The benefits and options available for chemotherapy and palliation of carcinoma of the gallbladder are the same as those for cholangiocarcinoma which is discussed in the next section.

Survival

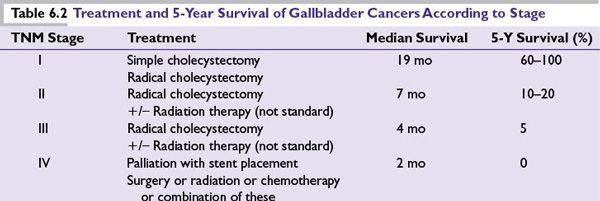

The various aspects of survival following treatment of gallbladder cancers according to stage are given in Table 6.2.

CARCINOMA OF THE BILE DUCTS (CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA)

■Cholangiocarcinomas arise from the epithelial cells of either intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts.

■Cholangiocarcinoma accounts for 3% of all GI malignancies. The reported incidence within the Unites States is one to two cases per 100,000 population.

■For some unclear reasons the incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma has been steadily rising over the past two decades, while rates of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas have been declining.

■Incidence typically increases with age. Median age at diagnosis is between 50 and 70 years. However patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and those with choledochal cysts tend to present significantly earlier.

■In contrast to gallbladder cancer, cholangiocarcinomas are more common in males.

■Cholangiocarcinomas are subdivided into proximal extrahepatic (perihilar or Klatskin tumor; 50% to 60%), distal extrahepatic (20% to 25%), intrahepatic (peripheral tumor; 20% to 25%), and multifocal (5%) tumors.

■Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are more common than intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas, and perihilar cholangiocarcinoma is the most common type.

Etiology

A number of risk factors have been associated with the disease in some patients; however, no specific predisposing factors have been identified.

■Inflammatory conditions: PSC is associated with an annual risk of 0.6 to 1.5% per year and a 10% to 15% lifetime risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma. Ulcerative colitis and chronic intraductal gallstone disease also increase risk. Nearly 30% of cholangiocarcinomas are diagnosed in patients with coexistent ulcerative colitis and PSC.

■Bile duct abnormalities: Caroli disease (cystic dilatation of intrahepatic ducts), bile duct adenoma, biliary papillomatosis, and choledochal cysts increase risk. The overall incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in these patients can be as high as 28%.

■Infection: In Southeast Asia, the risk can be increased 25- to 50-fold by parasitic infestation from Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis. These parasitic infections are more commonly associated with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. An association with viral hepatitis has also been seen recently. A higher than expected rate of hepatitis C-associated cirrhosis was noted in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. An association with hepatitis B has also been suggested.

■Genetic: Lynch syndrome II and multiple biliary papillomatosis are associated with an increased risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma. Biliary papillomatosis should be considered a premalignant condition as one study noted that up to 83% will undergo malignant transformation. More recently, certain genetic polymorphisms (NKG2D) have been determined to be possible risk factors for developing cholangiocarcinoma.

■Miscellaneous: Smoking, toxic exposures, such as thorotrast (a radiologic contrast agent used in the 1960s), asbestos, radon, and nitrosamines are also known to increase the risk. Recently, patients with diabetes or a metabolic syndrome have been noted to have an increased risk of developing a cholangiocarcinoma as well.

Clinical Features

Cholangiocarcinomas usually become symptomatic when the biliary system becomes blocked.

■Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma usually presents with symptoms and signs of cholestasis (icterus, pale stools, dark urine, and pruritus or cholangitis, which includes pain, icterus, and fever). Laboratory studies will typically suggest biliary obstruction with elevated direct bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase.

■Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma may present as a mass, be asymptomatic, or produce vague symptoms such as pain, anorexia, weight loss, night sweats, and malaise. These patients are less likely to be jaundiced.

Diagnosis

Making a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma preoperatively can be challenging. The diagnosis is frequently based on the clinical scenario, serology, and radiographic findings but without histologic confirmation. This is an important issue because up to 33% of patients with imaging and symptoms suggestive of cholangiocarcinoma will have benign disease. Such a diagnosis in the absence of tissue should be made only after efforts are taken to prove the diagnosis by use of cytologic or pathologic evaluation.

■A cholestatic serologic picture may be seen as previously described. Liver function tests may be elevated, particularly with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Tumor markers such as CEA and CA-19-9 by themselves are neither sensitive nor specific enough to make a diagnosis. CEA level > 5.2 ng/mL had a sensitivity and specificity of 68% and 82%, respectively. Some tumors produce low levels or no CA 19-9. In one series, a level >180 units/mL had a sensitivity of 67%; however, the specificity was 98%.

■Ultrasonography is the first-line investigation for suspected cholangiocarcinoma, usually to confirm biliary duct dilatation, localize the site of obstruction, and to rule out cholelithiasis. This technique can often overlook masses and is poor at delineating anatomy.

■CT/MRI is recommended as part of the diagnostic workup of cholangiocarcinoma, intrahepatic tumors in particular. These imaging modalities can help determine tumor resectability by evaluating the tumor and the surrounding structures (major vessels, lymph nodes, presence of metastases).

■Cholangiography: MRCP is noninvasive and is considered a safer alternative to ERCP or PTC. MRCP provides excellent imaging of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts and can create three dimensional imaging of the biliary tree and the vascular structures. This provides valuable information about disease extent and surgical options. Due to their ability to obtain brushings from as well as stent across strictures within the biliary tree, ERCP and/or PTC offer both diagnostic and therapeutic value in the workup and management of biliary obstruction; however, the diagnostic yield on cytology obtained from biliary brushings is notoriously suspect with sensitivities and specificities of roughly 50% being the norm.

■EUS may be useful in visualizing the extent of tumor and lymph node involvement of distal bile duct lesions. Its role in proximal bile duct lesions is less clear.

■PET scan is used to identify metastatic disease which could alter surgical management.

Pathology

■Adenocarcinomas account for 90% to 95% of tumors. The remainder is squamous cell carcinomas. They are graded as well, moderately and poorly differentiated, and are further divided into sclerosing, nodular, and papillary subtypes. Patients with papillary tumors present with earlier disease and have the highest resectability and cure rates; however, they are unfortunately the least common of the three subtypes.

■Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratins 7 and 20 can help differentiate intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CK7+, CK20–, CDX2–) from colorectal metastatic lesion (CDX2+, CK20+).

Staging

■The AJCC has developed the staging systems for cholangiocarcinomas. The TNM staging system is primarily based upon the extent of ductal involvement by the tumor.

■Previously, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas were staged identical to hepatocellular carcinoma. In the seventh edition of the AJCC Staging Manual, however, there is a new staging system independent of the one used for HCC. This revised system was validated by a study showing improved survival predictability correlating with the new TNM system.

■The seventh edition staging system for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas separates perihilar and distal bile duct tumors. These changes have improved the prognostic stratification of the TNM staging system. Please refer to the seventh edition AJCC Staging Manual for details.

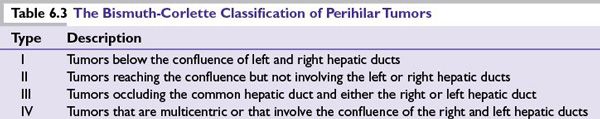

■Cancers arising in the perihilar region have been also further classified according to their patterns of involvement of the hepatic ducts, the Bismuth-Corlette classification (Table 6.3).

Treatment

Surgery

Except in the case of distal common bile duct cancer, cholangiocarcinoma is a disease that, when managed surgically, often times requires major hepatic resection (segmentectomy, anatomic lobectomy, trisegmentectomy) with or without bile duct resection/reconstruction. Therefore, the general principles of such resection(s) should be reviewed.

From the standpoint of major hepatic resection, the surgical principles are simple and revolve primarily around leaving the patient with an adequate volume of a functioning liver remnant to sustain them postoperatively. This requires executing an operation that ensures both adequate inflow to (hepatic artery and portal vein) and outflow from (hepatic vein and bile duct) the remnant liver.

Generally speaking, roughly 75% of a patient’s liver volume can safely be resected; however, consideration must be given to the health of the background liver. Such consideration includes underlying chronic liver disease (hepatitis, prior alcohol use, steatosis/steatohepatitis) as well as any acute insults, which in the case of cholangiocarcinoma often times involves cholestasis. The former issues can limit the extent of resection that can safely be performed, while the latter often times necessitates preoperative delays while the cholestatic picture resolves.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree