RISK FACTORS

Most patients will have no identifiable risk for developing leukemia. Table 23.1 lists the conditions that are identified with an increased risk for developing acute leukemia. Most studies have evaluated the relationship between the risk factors and AML. The conditions that are mostly associated with AML are chronic benzene exposure, exposure to ionizing radiation, and previous chemotherapy.

Ionizing Radiation Exposure Explored in Atomic Bomb Survivors

■Ionizing radiations have a latency period of 5 to 20 years and a peak period of 5 to 9 years in atomic bomb survivors.

■They exhibit a 20- to 30-fold increased risk of AML and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

Chemotherapy

■Therapy-related AML may account for 10% to 20% of new cases.

■Leukemia associated with alkylating agents may be associated with cytogenetic changes of chromosomes 5, 7, and 13. Often there is a multiyear latent-phase myelodysplastic syndrome preceding the development of AML.

■Topoisomerase II agents, often with an abnormal chromosome 11q23 in the blasts, can rapidly evolve after initial therapy. Usually, these are preceded by only a brief myelodysplastic state rapidly evolving to AML.

■Previous high-dose therapy with autologous transplant leads to a cumulative risk of 2.6% by 5 years, especially with total body irradiation (TBI)-containing regimens.

CLINICAL SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

■Ineffective hematopoiesis: Results from marrow infiltration by the malignant cells

•Anemia: pallor, fatigue, and shortness of breath

•Thrombocytopenia: epistaxis, petechiae, and easy bruising

•Neutropenia: fever and pyogenic infection

•Skin: Leukemia cutis in 10%

•Gum hypertrophy: Especially in monocytic leukemia (AML M5)

•Granulocytic sarcoma: Localized tumor composed of blast cells; imparts poorer prognosis; occasionally extramedullary leukemia masses associated with 8;21 translocation

•Liver, spleen, and lymph nodes: Common in ALL, occasionally in monocytic leukemia (AML M5)

•Thymic mass: Present in 15% of ALL in adults

•Testicular infiltration: Also a site of relapse for ALL

•Retinal involvement: May occur in ALL

■Central nervous system (CNS) and meningeal involvement

•5% to 10% of cases at diagnosis, mainly ALL, inv(16) (French–American–British [FAB] M4Eo), and high blast count

•Analysis and prophylaxis are given in ALL to decrease CNS relapse.

•Symptoms: Headache and cranial nerve palsy, but mostly asymptomatic

■Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and bleeding

•Very common with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL); the mechanism is related to tissue factor release by granules and fibrinolysis; generally improves with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) of which early initiation is imperative.

•Can be present in AML inv(16) or monocytic leukemia or can be related to sepsis.

■Leukostasis

•Occurs with elevated blast count

•Symptoms result from capillary plugging by leukemic cells.

•Common signs: dyspnea, headache, confusion, and hypoxia

•Initial treatment includes leukapheresis, aggressive hydration, and chemotherapy to rapidly lower the circulating blast percentage with drugs (e.g., oral hydroxyurea or intravenous cyclophosphamide).

•Transfusions should be avoided because these may increase viscosity.

•Leukapheresis is repeated daily in conjunction with chemotherapy until the blast count is <50,000.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

■History and physical examination are an essential part of diagnosis of acute leukemia.

■Complete blood count (CBC), differential and manual examination of peripheral smear, and peripheral blood flow cytometry are considered when circulating blasts are sufficiently abundant to establish a diagnosis.

■Coagulation tests include prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), D-dimer, and fibrinogen.

■Electrolytes with calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and uric acid. Low glucose, potassium, and PO2 (partial pressure of oxygen) can occur with delay in analysis of high blast count.

■Bone marrow biopsy and aspirate (with analysis for morphology), cytogenetics, flow cytometry, and cytochemical stains (Sudan black, myeloperoxidase, acid phosphatase, and specific and nonspecific esterase) are used for diagnosis.

■Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) testing of patients who are transplant candidates—the test is performed before the patient becomes cytopenic. Specimen requirements are minimal when DNA-based HLA typing is performed.

■Hepatitis B and C, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, human T-cell leukemia virus, and human immunodeficiency virus antibody titers are obtained.

■Pregnancy test (β-human chorionic gonadotropin), if applicable

■Electrocardiogram (ECG) and analysis of cardiac ejection fraction should be done prior to treatment with anthracyclines.

■Lumbar puncture: Performed when signs and symptoms of neurologic involvement are present. Low platelets should be corrected. The procedure may be performed after reduction of peripheral blast count to avoid inoculation of blasts into uninvolved cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Obtain cell count, opening pressure, and protein level, and submit cytocentrifuge specimen for cytology.

■Central venous access should be obtained. An implanted port-type catheter is not recommended. Coagulation abnormalities should be corrected if present. It is often possible to initiate induction therapy with normal peripheral veins and await subsidence of coagulopathy to reduce risk of procedural complications.

■Supplemental testing of fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) assay for 15;17 translocation is performed when APL is suspected; and a BCR-ABL test is performed when CML in blast phase or ALL is suspected.

■Cytogenetic and gene mutation analysis of blasts will contribute dramatically to subsequent preferred management and prognosis.

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

The initial management of acute leukemia involves the following:

■Hydration with IV fluids (2 to 3 L/m2 per day).

■Tumor lysis prophylaxis should be started.

■Blood product support suggestions for prophylactic transfusions are hemoglobin level <8 and platelet level <10,000. Platelet trigger threshold can be higher in the context of fever or bleeding (<20,000 suggested), cryoprecipitate can be used if fibrinogen level is <150, and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) can be used to correct significantly elevated levels of PT and PTT. Platelet trigger should be increased in APL patients to <50,000. The minimum “safe” platelet level required to prevent spontaneous hemorrhage is not known. Additional platelet optimization strategies include avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and clopidogrel-like agents.

■Blood products should be irradiated and a WBC filter (if CMV-negative blood inventory is not available) should be used in those patients who are future allogeneic transplant candidates.

■Fever and neutropenia require blood and urine cultures, followed by treatment with appropriate antibiotics (see Chapter 36), and imaging.

■Therapeutic anticoagulation should be given with extreme caution in patients during periods of extreme thrombocytopenia. Adjustment of prophylactic platelet transfusion thresholds or anticoagulants is required.

■Suppression of menses: Medroxyprogesterone (Provera) 10 mg daily or twice daily.

Tumor Lysis Syndrome

■Tumor lysis syndrome can be spontaneous or can be induced by chemotherapy.

■Risk factors include elevated uric acid, high WBC count, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and high tumor burden.

■Laboratory tests indicate elevated potassium, phosphorus, and uric acid; with a resulting decrease in calcium.

■The patients should be initiated on allopurinol 300 mg twice daily for 3 days, followed by once daily until risk is resolved.

■For hydration, alkalinizing fluids (0.5 NS with 50 mEq sodium bicarbonate) could be considered to increase solubility of uric acid, minimizing intratubular precipitation. Caution should be taken since alkanizing the urine also promotes calcium–phosphate complex deposition, and considering the availability of uricolytic agents (rasburicase), alkalinization is typically not utilized.

■Rasburicase (Elitek) should be used if the patient has hyperuricemia and an elevated creatinine on presentation or has hyperuricemia uncontrolled with allopurinol. Prophylactic rasburicase is not necessary with proper uric acid monitoring, due to quick onset of action of rasburicase.

■Hemodialysis may be required in refractory cases or urgently in the setting of life-threatening hyperkalemia, or volume overload if oliguric (see Chapter 38).

CLASSIFICATION

Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

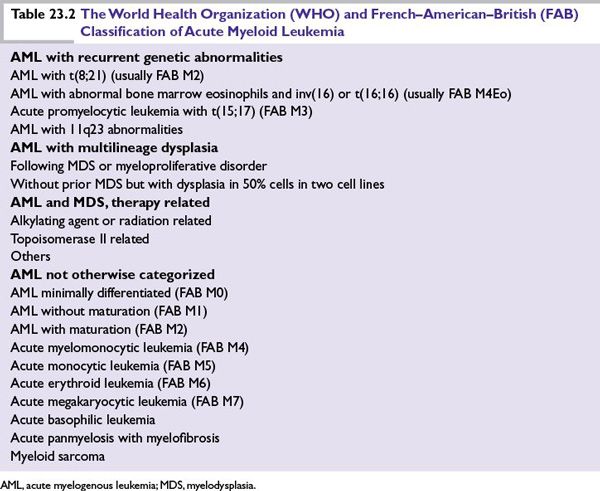

There are two current systems to classify AML. The most commonly used criterion is from the World Health Organization (WHO) and incorporates recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities and prognostic groups (Table 23.2). Marrow blasts should make up 20% of the nucleated cells within the aspirate unless t(8;21) or inv(16) is present. The FAB classification is also used and classifies AML into eight subtypes. The blasts may be characterized as myeloid lineage by the presence of Auer rods; a positive myeloperoxidase, Sudan black, or nonspecific esterase stain; and the immunophenotype shown by flow cytometry. Cell surface markers associated with myeloid cell lines include CD13, CD33, CD34, c-kit, and HLA-DR. Monocytic markers include CD64, CD11b, and CD14. CD41 (platelet glycophorin) is associated with megakaryocytic leukemia, and glycophorin A is present on erythroblasts. HLA-DR–negative blast phenotype is commonly seen in APL and serves as a rapidly available test in confirming the suspicion of this subtype requiring a specific induction therapy.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

The WHO classification of ALL divides the disease into precursor B-cell, precursor T-cell, and Burkitt-cell leukemia. Immunophenotyping of B-lineage ALL reveals lymphoid markers (CD19, CD20, CD10, TdT, and immunoglobulin). T-cell markers include TdT, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, and CD7. Burkitt-cell leukemia is characterized by a translocation between chromosome 8 (the c-myc gene) and chromosome 14 (immunoglobulin heavy chain), or chromosome 2 or 22 (light chain) regions.

PROGNOSTIC GROUPS

Acute Myelogenous Leukemia

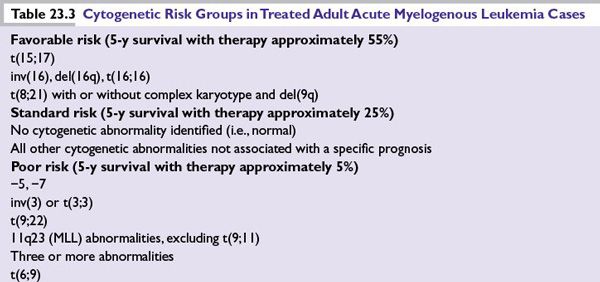

Those patients who are older (>60 years) and those with an elevated blast count at diagnosis (>20,000) have a worse prognosis. Chemotherapy-related AML and prior history of myelodysplasia (MDS) impart a lower chance of obtaining complete remission (CR) and long-term survival. Table 23.3 illustrates the prognostic groups according to cytogenetics.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree