Fig. 14.1

Possible intraductal and discontinuous peritumoral spread of DCIS

These issues warrant thorough preoperative assessment (usually breast MRI). Most DCIS are non-palpable lesions (mostly microcalcifications) so careful preoperative localization of the index lesion is essential to guide the surgeon and avoid wider or incorrect excisions (unless mastectomy is the scheduled treatment). Such localization must be programmed preoperatively and undertaken by a radiologist using permanent dye, a radioisotope (radioguided occult lesion localization (ROLL)), a metal wire, or a gel-mark for the rare lesions seen only upon ultrasound.

Stereo-guided mammography is a technical method for localizing a nonpalpable DCIS. Moreover, a clip must be left within the breast gland by the radiologist once carrying out percutaneous stereo-guided biopsy. This is because microcalcifications can be removed completely by the biopsy and because a clip can be used as a label by the surgeon after the excision. For nonpalpable lesions treated by conservative procedures, the surgeon, in addition to the use of preoperative guides, ought to confirm the correctness of the excision through an intraoperative radiograph of the removed breast tissue. The radiograph can demonstrate the radiologic clip or the index microcalcifications, and give an idea of resection margins. Rarely, an ultrasound has to be carried out to confirm the lesion (or a gel-mark) in removed tissue if the tumor is not seen by mammography.

As mentioned above, mastectomy is sometimes necessary for DCIS. Three conditions mandate a mastectomy [10]: high tumor extension/breast volume ratio; multicentric tumors; postoperative radiotherapy (RT) is not possible.

If a conservative procedure is chosen, which minimum value of the margin value can be considered to be sufficient? This is definitively a controversial topic in the surgical treatment of DCIS. At the Philadelphia 1999 consensus conference [10] a 10-mm margin was deemed necessary. However, at the St. Gallen consensus conference in 2009, a 2-mm margin was considered acceptable. At the same consensus conference, for margins <2 mm, 48% of experts considered reexcision not to be necessary, whereas it was debatable for 9%, and absolutely necessary only for 43% of those present. RT is usually carried out after DCIS surgery, several authors from North America consider a margin to be negative if the tumor does not extend to the surface of the inked specimen.

In summary, because DCIS is, by definition, a local disease, appropriate local treatment with complete tumor removal is the primary goal of DCIS therapy. A failure in DCIS treatment is represented by local recurrence. Recurrences are invasive in 50% of cases and even more for young patients with G3, comedo-necrosis tumors.

A practical guide to local treatment is the validated van Nuys Prognostic Index (VNPI) score (Table 14.1). If the score ranges from 4 to 6, lumpectomy alone is sufficient; a score of 7 to 9 mandates radiotherapy; and a score of 10 to 12 necessitates mastectomy.

Table 14.1

Van Nuys Prognostic Index

Score | Dimension (mm) | Margin Status (mm) | Histology | Histology Age (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | <15 | >10 | Non-high grade | >61 |

No necrosis | ||||

Nuclear grade | ||||

1–2 | ||||

2 | 16–40 | 1–10 | Non-high grade | 40–60 |

Necrosis | ||||

Nuclear grade | ||||

1–2 | ||||

3 | >40 | <1 | High grade | <39 |

Nuclear grade 3 |

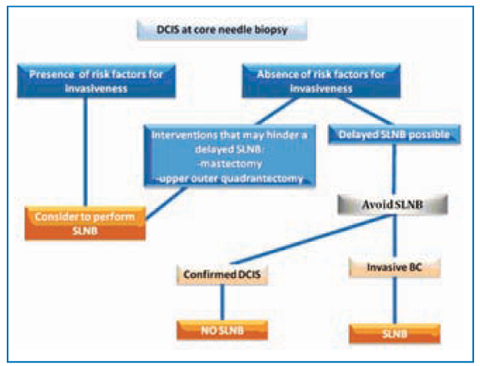

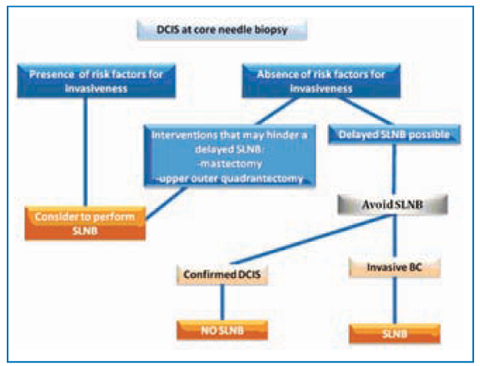

Axillary Surgery

Infiltration of lymphatic vessels and lymph-node involvement are, by definition, not possible for DCIS, because the basement membrane is not broken by tumor cells. Notwithstanding this principle, SLNB has a role in DCIS surgery. From 5% to 44% (mean, 20%) [11] of preoperative diagnoses of DCIS are micro-invasive or invasive cancers at definitive pathology report. Thus, a second intervention for axillary staging is necessary in such cases.

Another issue is positive SLNB at definitive pathology report, even in confirmed cases of DCIS (which has been estimated to be 3.7% in a recent study [12]). This could be interpreted as a pathology sampling failure and therefore a sign of infiltration or a sign of cell dislocation during diagnostic and surgical procedures.

No randomized trials have shed light on this topic. The choice to carry out SLNB in the case of a preoperative diagnosis of DCIS is based mainly on the rationale of avoiding further interventions. Several risk factors were identified in one study [13]. Four conditions can be identified as risk factors of invasion after a core biopsy diagnosis of DCIS:

Palpable lump;

Mass on mammography;

Intermediate or poor tumor grade;

Microcalcification area wider than 2.5 cm.

In the case of mastectomy, SLNB should always be done because this surgical procedure hinders the future possibility of undertaking SLNB. Some authors advocate that this policy should also apply to upper outer quadrant excisions.

In terms of everyday practice, the flowchart in Fig. 14.2 can be proposed as a guide for carrying out SLNB in DCIS.

Fig. 14.2

Sentinel lymph node biopsy in ductal carcinoma in situ

Radiotherapy

The aim of local treatment of DCIS is avoidance of local recurrence, which is invasive in ≈50% of cases. To reach such a goal, RT is a crucial adjuvant support to surgical excision whenever a conservative approach is chosen.

Level-I evidence from four randomized clinical trials (NSABP B 17, EORTC 10853, SweDCIS Trial, UKCCCR Trial) suggests that RT reduces ipsilateral local recurrence by .50% compared with conservative resection alone. No differences were found in contralateral BC and mortality at 10 years. Whole-breast RT was the adopted modality. Results applied to all subgroups of patients. It was not possible to identify subset of patients who might avoid RT, as expressed in the VNPI. The VNPI was derived from a retrospective analysis and has not been validated (even by recent prospective analyses).

New recent modalities of RT are partial breast irradiation (PBI), also known as accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) and intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT), which is an intraoperative modality of PBI. Several methods using different energy sources have been described as external irradiation or as intracavitary or interstitial brachytherapy. The rationale for these novel methods is that local recurrence is mostly very near to the tumor bed and that recurrences “elsewhere” in the breast are <20% (<1% per year, similar to the value for contralateral tumors). Furthermore, these modalities reduce the conventional 5.7-week course of whole-breast irradiation to the same operative day or ≥4–5 postoperative days.

The primary purpose of selecting patients for APBI is to find a subgroup with a low risk of occult disease far from the lumpectomy site (or at least not too far) in an area not reached by the chosen APBI modality. Among all prospective nonrandomized and randomized PBI trials with ≥4 year follow-up, none involved DCIS patients except for the American Society of Breast Surgeons MammoSite APBI trial. Therefore, PBI should be used with caution in DCIS cases outside a clinical trial. According to recommendations set by the Groupe Européen de Curiethérapie-European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (GECESTRO), DCIS cases cannot be in low-risk groups, or be considered good candidates for PBI; instead, they should be regarded as intermediate-risk patients for PBI. Similarly, in the consensus statement provided by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), DCIS cases are not listed among the “suitable” cases for PBI, whereas they can be considered part of the “uncautionary” group if the dimensions are <3 cm and “unsuitable” if >3 cm.

IORT is a type of PBI that uses a high, single dose irradiation as the sole or boost treatment at the resection site. It can also be used for nipple-areola treatment in case of nipple-areola-sparing mastectomy. This modality is carried out before the definitive pathology report, so thorough evaluation after the report is essential for selecting the appropriate therapy.

Systemic Therapy

Although DCIS is a local disease, individualized treatment for DCIS patients should also take into account systemic therapy. DCIS recurrences are invasive in ≈50% of cases, and a patient with a previous DCIS is a higher risk for contralateral BC. Just as RT reduces ispilateral local recurrence by ≈50%, it is well known (from randomized clinical trials) that tamoxifen reduces any breast cancer event (defined as combined ipsilateral plus contralateral breast events) by ≈30% [14] without any effect on overall survival. Therefore, it is reasonable to advise systemic treatment with tamoxifen to selected DCIS cases with hormone receptor-positivity. To identify subsets of patients who might benefit from systemic therapy, different approaches can be considered. A nomogram from Memorial Sloan.Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) has been proposed that considers conventional clinical and pathological parameters. Such a nomogram has not been validated from different institutions. In the near future, molecular profiling and molecular biology-based scores could potentially improve risk stratification for women with DCIS, helping to guide physicians and patients towards the correct therapeutic choice. There are ongoing trials aiming to find alternative treatments. These include aromatase inhibitors and anti-Her2 agents such as trastuzumab and lapatinib.

Follow-up

There is virtual general consensus among specialists involved in BC with regard to follow-up for DCIS patients: history-taking and physical examination every 6–12 months for 5 years and then annually, accompanied by annual mammography. Further investigations can be considered for those women treated by hormonal therapy.

Lobular Carcinoma In Situ (LCIS)

According to the 2003 World Health Organization (WHO) definition, noninvasive lobular carcinoma falls within the category of lobular intra-epithelial neoplasia (LIN), which comprises three identities:

LIN 1: atypical lobular neoplasia or hyperplasia;

LIN 2: lobular carcinoma in situ, classic type;

LIN 3: lobular carcinoma in situ with central necrosis or pleomorphic type or with signet ring cells.

Since its first description in 1941 by Foote and Stewart, LCIS treatment has ranged from simple biopsy to bilateral mastectomy. This diversity (which in part is present today) is dependent upon whether it is considered to be a marker of increased BC for both breasts (“risk factor theory”) or a real BC precursor (“precursor theory”).

In a literature review spanning decades of LIN series [15], a detailed comparison of these theories was carried out. Recently, the precursor theory has gained respect after demonstration of a common lack of expression of the Ecadherin adhesion cell molecule for LIN and invasive lobular neoplasia, suggesting a possible transformation of LIN into invasive lobular BC. Moreover, BC, developed after diagnosis of LIN, is lobular in 30% of cases as compared with 16% in the general population. Usually, an ipsilateral BC develops in the same quadrant of LIN, and the rate of ipsilateral BC is slightly higher than contralateral BC (51% vs 41%, respectively). There are many issues favoring the isk factor theory: BC develops >10 years after a diagnosis of LIN in 50% of cases; the percentage of contralateral BC cases is not too different from ipsilateral invasive BC; the vast majority of BC, diagnosed after a LIN diagnosis, do not contain invasive lobular pathological features.

A LIN report after breast biopsy should prompt surgical local excision. Instead, some authors believe that proceeding with an excision is not necessary, but the possibility of cancer progression or of a surrounding DCIS (or even invasive BC) must be taken into account. Mastectomy (especially bilateral) is becoming outdated because LIN around an invasive BC does not have any effect on recurrence rate or survival. Thus, bilateral mastectomy can be deemed a level-V recommendation only. An important topic remains margin status. Absence of prospective randomized clinical trials and the paucity of cases in most studies limit any conclusions to be drawn. Guidelines are derived mostly from retrospective reviews and inferences from experts. Many experts judge LIN 3 similar to DCIS and treat it equally.

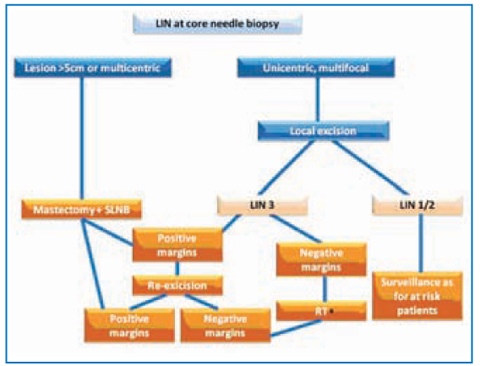

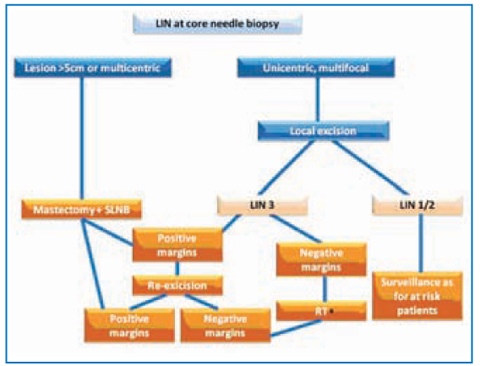

If LCIS is interpreted to be a risk factor, a chemopreventive therapies could be proposed to patients. A National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) study showed that tamoxifen reduces the chances of development of invasive BC after LCIS in 56% of cases; the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) study showed similar results for raloxifene. The follow-up for LCIS can be planned as that for DCIS. Figure 14.3 can be proposed as a guide for LIN treatment.

Fig. 14.3

Treatment for lobular carcinoma in situ. *To be evaluated case by case; LIN, lobular intra-epithelial neoplasia; SLNB, sentinel lymph-node biopsy; RT, radiotherapy

Paget’s Disease (PD)

PD of the breast was first detailed by James Paget in 1874. He described 15 women with chronic eczematous lesions of the nipple-areola skin with an associated intraductal carcinoma of the mammary gland.

PD is seen almost exclusively in women; male reports are anecdotal. The appearance of a nipple-areola chronic rash must be recognized promptly to initiate the appropriate diagnostic workup and detect underlying BC. A similar rash can be seen in the skin of external male and female genitalia, but this condition, known as extramammary PD, is not associated with breast PD in terms of pathophysiology and etiology.

The origin of PD can be traced to the superficial extension (epidermotropism) of malignant ductal epithelial cells derived from the underlying breast gland or an intraepidermal origin (“gin situ transformation theory”), as described by Muir in 1939. Malignant cells extend from luminal lactiferous ductal epithelium and infiltrate the epidermis, causing the well-known chronic rash. Most dedicated studies have shown shared genetic changes and biomarkers between PD cells and underlying breast adenocarcinoma cells. The exact worldwide frequency of PD is not known, but ≈1–3% of BC are associated with PD and nearly 90–100% of PD have a DCIS or invasive BC in the gland beneath (either identifiable or not). If there are imaging findings of breast lesions associated with PD, these are invasive BC in 90% of cases and only 10% in DCIS whereas, for PD lesions without any other finding, a DCIS is found in ≈70% of cases in the gland beneath and invasive BC in the remaining 30% [16].

Once signs and symptoms such as rash, itch, erythema, burning and sometimes bloody nipple discharge (associated with skin thickening and nipple inversion) raise the suspicion of PD, a diagnostic workup must be started. Physical examination, MXR, ultrasound and cytology testing by nipple-areola scraping are the first step. If negative, a dermatology consultation and shortterm follow-up (2 weeks) might be a sensible option. Otherwise, if treatment for a positive or suspicious lesion has to be taken, after considering further investigations such as breast MRI, the mammary gland should be evaluated. In the case of negative tests, but very suspicious physical examination, a fullthickness biopsy must be undertaken. If an associated breast lesion is identified, histologic confirmation should be completed. Confirmed BC with suspicious PD requires full-thickness skin biopsy to rule out possible associated PD.

Eventually, after the diagnostic workup, two situations can be outlined: PD with associated BC or PD without an identifiable underlying BC. The former case has to be treated according to BC stage. Surgical excision must include the nipple-areola complex (NAC) in continuity or not with the BC. Adjuvant therapies are chosen based on the parameters of BC. PD can be addressed only with the following surgical options: central quadrantectomy including NAC excision, simple mastectomy, or skin-sparing mastectomy. These options have different reconstruction options. Axillary staging with a SLB is a sensible choice if mastectomy is carried out for DCIS and conservative procedures because of the high number of invasive BC associated [15]. In case of a breastconservation surgery, RT is indicated afterwards to provide a boost to the surgical site. As for DCIS, patients with treated PD are at a higher risk of developing any BC event in the future, which is why systemic therapy with tamoxifen is a viable option to be discussed with the patient.

Invasive Breast Cancer

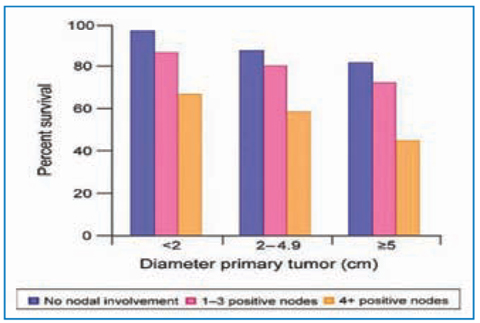

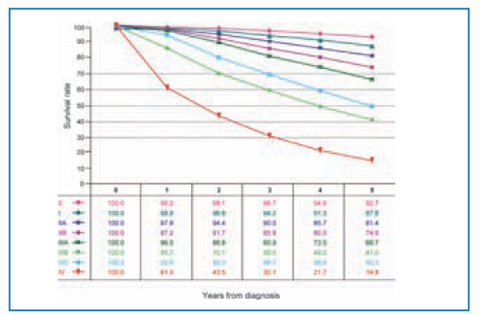

According to the seventh edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual, the categories of BC detailed in Table 14.2 can be identified [1]. Please also see Figs 14.4–14.6.

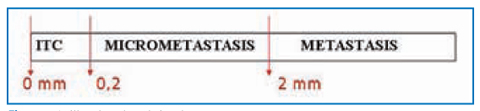

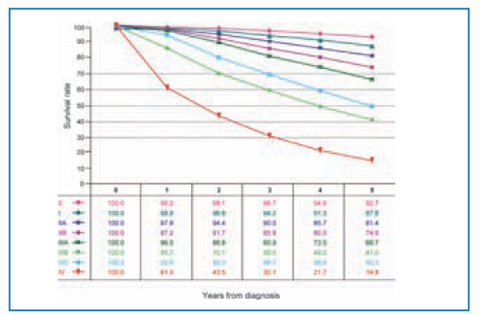

Fig. 14.4

Axillary lymph-node involvement

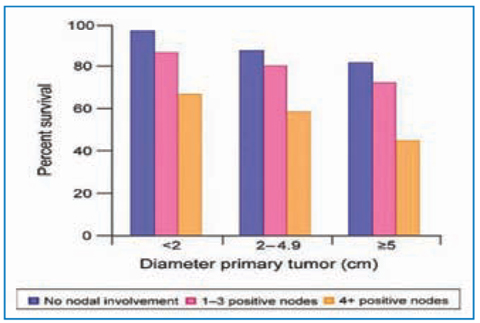

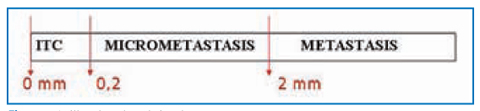

Fig. 14.5

Percentage survival at 5 years according to size of primary tumor and number of nodes involved. Material from AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th edition). Reproduced with permission from the AJCC

Fig. 14.6

Survival according to AJCC stage. Material from AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th edition). Reproduced with permission from the AJCC

Table 14.2

Categories of breast cancer as stipulated by the AJCC

pT1: Tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension | • pT1mi: Microinvasion 0.1 cm or less |

•pT1a: More than 0.1 cm but not more than 0.5 cm | |

• pT1b: More than 0.5 cm but not more than 1 cm | |

• pT1c: More than 1 cm but not more than 2 cm | |

pT2: Tumor 2–5 cm across | |

pT3: Tumor greater than 5 cm across | |

pT4: Tumor of any size with direct extension to chest wall* and/or to skin (ulceration or skin nodules) | • Pt4a: chest wall |

• pT4b: ulceration, ipsilateral satellite skin nodules, or skin edema (including peau d’orange) | |

• pT4c: 4a and 4b above | |

• pT4d: inflammatory carcinoma (diffuse, brawny induration of the skin with an erysipeloid edge, usually with no underlying mass) | |

Regional lymph nodes (pN) | • Axillary (ipsilateral): interpectoral (Rotter) nodes and lymph nodes along the axillary vein and its tributaries; |

• Infraclavicular (subclavicular) (ipsilater); | |

• Internal mammary (ipsilateral); | |

• Supraclavicular. | |

Note: Intramammary lymph nodes are coded as axillary lymph nodes level I. | |

Note: Any other lymph node metastasis is coded as a distant metastasis (pM1) (cervical or controlateral internal mammary lymph nodes) | |

pNx | Regional lymph node cannot be assessed |

pN0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

pN0(sn) | No sentinel lymph node metastasis |

Isolated tumor cells (ITCs) | |

pN0(i-) | No regional lymph node metastasis histologically, negative morphological findings (E&E) for ITC |

pN0(i+) | No regional lymph node metastasis histologically, positive morphological findings (E&E) for ITC |

pN0(mol-) | No regional lymph node metastasis histologically, negative non-morphological (RT-PCR) findings for ITC |

pN0(mol+) | No regional lymph node metastasis histologically, positive non-morphological (RT-PCR) findings for ITC |

ITCs in sentinel lymph nodes | |

pN0(sn)(i-) | |

pN0(sn)(i+) | |

pN0(sn)(mol-) | |

pN0(sn)(mol+) | |

pN1mic: Micrometastasis | |

Larger than 0.2 mm and/or more than 200 cells, but none larger than 2 mm (Fig. 14.4) | • pN1a: Metastasis in 1–3 axillary lymph node(s) |

• pN1b: Internal mammary lymph nodes with microscopic or macroscopic metastasis detected by sentinel lymph node biopsy but not detected clinically | |

• pN1c: Metastasis in 1–3 axillary lymph nodes and internal mammary lymph nodes with microscopic or macroscopic metastasis detected by sen tinel lymph node biopsy but not detected clinically

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|