Primary tumor (T)

TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0 No evidence of primary tumor

Tis Carcinoma in situ: intra-epithelial or invasion of lamina propria

T1 Tumor invades submucosa

T2 Tumor invades muscularis propria

T3 Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into pericolorectal tissues

T4a Tumor penetrates to the surface of the visceral peritoneum

T4b Tumor directly invades or is adherent to other organs or structures

Regional lymph nodes (N)

NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0 No regional lymph node metastasis

N1 Metastasis in 1.3 regional lymph nodes

N1a Metastasis in 1 regional lymph node

N1b Metastasis in 2.3 regional lymph nodes

N1c Tumor deposit(s) in the subserosa, mesentery, or non-peritonealized pericolic or perirectal tissues without regional nodal metastasis

N2 Metastasis in ≥4 lymph nodes

N2a Metastasis in 4–6 regional lymph nodes

N2b Metastasis in ≥7 regional lymph nodes

Distant metastasis (M)

M0 No distant metastasis

M1 Distant metastasis

M1a Metastasis confined to 1 organ or site (e.g., liver, lung, ovary, non-regional node)

M1b Metastases in >1 organ/site or the peritoneum

Table 3.2

Anatomic stage/prognostic groups

Stage | T | N | M | Dukes | MAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | — | — |

I | T1 | N0 | M0 | A | A |

T2 | N0 | M0 | A | B1 | |

IIA | T3 | N0 | M0 | B | B2 |

IIB | T4a | N0 | M0 | B | B2 |

IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 | B | B3 |

IIIA | T1-T2 | N1/N1c | M0 | C | C1 |

T1 | N2a | M0 | C | C1 | |

IIIB | T3-T4a | N1/N1c | M0 | C | C2 |

T2-T3 | N2a | M0 | C | C1/C2 | |

T1-T2 | N2b | M0 | C | C1 | |

IIIC | T4a | N2a | M0 | C | C2 |

T3-T4a | N2b | M0 | C | C2 | |

T4b | N1-N2 | M0 | C | C3 | |

IVA | Any T | Any N | M1a | — | — |

IVB | Any T | Any N | M1b | — | — |

Staging Information

The features of the revised staging give more importance to the poor prognostic features of the depth of invasion despite fewer positive nodes.

T4 is divided between penetration to the surface of the visceral peritoneum and direct gross adherence to adjacent structures;

T1-2N2 is downstaged from stage IIIC to IIIA or IIIB depending on the number of nodes involved

Shift T4bN1 from IIIB to IIIC;

Subdivide T4/N1/N2;

Resolution of staging for issue of mesenteric deposits where nodal tissue is not identified;

Revised sub-staging of stage II based on depth of invasion, with addition of stage IIC;

Revised sub-staging of stage III based on node number (N1a, 1 node; N1b, 2–3 nodes; N2a, 4–6 nodes; N2b, ≥7 or more nodes);

Division of metastases to ≥1 sites in recognition of the possibility of a curative approach for aggressive treatment of a single site of metastases.

The seventh edition considers, together with the classic anatomic bases of T, N and M, some other important anatomic and serological prognostic factors validated by clinical studies and which are evidence-based and which assume prognostic value that influences patient care. Among the important anatomical factors are lymphatic vessel invasion (Lx: cannot be assessed; L0: absent; L1: present), venous invasion (V0: absent; V1: microscopic; V2: macroscopic), perineural invasion (PN: 1 present or 0 absent) and the residual tumor (Rx: cannot be assessed; R0: no residual; R1: microscopic residual; R2: macroscopic residual). The two principal serological prognostic factors are CEA (Cx: not assessed; C0: <5 ng/mL — normal; C1: >l5 ng/ml — elevated) and microsatellite instability (MSI). MSI is a marker of the functionality of the DNA repair enzyme system operating during cellular replication. MSI (higher (H) or lower (L) level) is especially significant in HNPCC and in ≈20% of sporadic cancers.

Sentinel Lymph Node (SLN) Biopsy

Since the 1980s, many studies have been conducted focusing on intraoperative identification of SLNs and/or complete mapping of lymph nodes using different technologies (e.g., vital coloration, intraoperative ultrasound and/or radioimmunoguided nodal mapping) [35,36]. The first aim was to eventually modify the extension of the resection that could be more limited in small lesions (frequently diagnosed in screening programs and eventually removed endoscopically) with negative SLNs, or more extended over the boundaries of classic lymphadenectomy in cases of aberrant lymphatic drainage. Furthermore, microscopic evaluation of node status in colon cancer is based on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, and has a non-negligible percentage of false-negative values (especially if we consider micrometastases), and cell clusters of diameter <0.2 mm are also associated with relevant recurrence of disease and lower 5-year survival rates. Correct identification of this false stage-II population can be achieved by a more sensible (but more expensive) immunohistochemical (IHC) test. The individualization of a SLN could help to reach this aim.

Treatment According to Stage of Colon Cancer

Stages

Stage 0: These cancers are in the inner lining of the colon; polypectomy or local excision through a colonoscope is often all that is needed. Colectomy may occasionally be needed if a tumor is too big to be removed by local excision.

Stage I: Several layers of the colon are penetrated from the cancer without spread outside the colon wall (or into nearby lymph nodes). Partial colectomy (i.e., surgery to remove the section of colon that has cancer and nearby lymph nodes) is the standard treatment without the need for additional therapy.

Stage II: Many of these cancers have grown through the wall of the colon and may extend into nearby tissue. They have not yet spread to the lymph nodes. Colectomy is usually the only treatment needed. However, adjuvant chemotherapy may be recommended if the cancer has a higher risk of returning because of certain factors: it looks very abnormal (is high grade) or has a dangerous histotype; shows MSI; has grown into nearby organs; the surgeon did not remove all the cancer and ≥12 lymph nodes; the cancer obstructs the colon or causes a perforation in the colon wall. Many research teams have studied the way to identify stage II because the risk of recurrence is greater. Petersen et al. [37] proposed a sub-classification of the prognostic index (PI) based on four elements subsequently considered by many other authors. Three of them have a score of 1: peritoneal involvement with or without ulceration; extramural or submucosal venous spread; or a involved or inflamed margin. The last element, perforation through the tumor, has a score of 2. Patients in stage II with a PI of ≥2 are to be considered at high risk and could be candidates for adjuvant therapy (see below). Even the pathological aspects of tumor necrosis as well as host systemic and local inflammatory responses are taken into account. Different criteria have been used to measure these variables, such as the Glasgow Prognostic Score [38] for systemic inflammatory responses, the Klintrup.Makinen criteria [39] for local inflammatory infiltrates and for the assessment of tumor necrosis. Richards et al. [40] confirmed by statistical means that tumor necrosis is a marker of a poor prognosis, independent of pathological stage, and that it is associated directly with an increase in the systemic inflammatory response and a decrease in local inflammatory cell infiltrates. This finding suggests that the impact of tumor necrosis on survival from CRC may be explained by close relationships with host inflammatory responses. Patients in stage II with extensive tumor necrosis are to be considered at high risk and could be candidates for adjuvant therapy.

Stage III: There is a spread to nearby lymph nodes, but cancer has not yet spread to other parts of the body. Partial colectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy is the standard treatment for this stage.

Stage IV: Distant organs and tissues such as the liver, lungs, peritoneum or ovaries can be affectted by colon cancer. If only a few small metastases are present in the liver or lungs and can be completely removed along with the colon cancer, surgery may prolong life and sometimes may even cure. Chemotherapy is typically given before and/or after surgery. Other options to destroy tumors in the liver include hepatic artery infusion, cryosurgery, radiofrequency ablation, or other non-surgical methods. If the cancer is too widespread to try to cure with surgery, colectomy or diverting colostomy may be needed in cases of bleeding or occlusion. Sometimes, such surgery can be avoided by inserting a stent into the colon during colonoscopy to keep the lumen patent. Most patients with stage-IV cancer will receive chemotherapy and/or targeted therapies to control the cancer.

Recurrent Colon Cancer

Recurrent cancer means that the cancer has returned after treatment. If the cancer comes back locally, surgery (often with previous and/or after chemotherapy) can stop recurrence, prolong life, and eventually cure the patient. If the cancer comes back at a distant site (liver, lung, others), surgery may be an option in some cases. If needed, chemotherapy can be tried first to shrink the tumor(s), and may be followed by surgery. If the cancer is too widespread for a surgical approach, chemotherapy and/or targeted therapies may be used depending on which (if any) drugs were received before the cancer returned and how long ago the patient received them, as well as general health status. Radiotherapy may be an option to relieve symptoms in some cases.

Adjuvant Therapy

In previous years, the standard of care for stage-III and -IV disease (and even some high-risk stage-II disease) was treatment with 5-fluorouracil (5FU) and leucovorin (LV) for six cycles with surgery or these agents alone in cases without a surgical indication. From 2004, with the results of the Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin/5-fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer (MOSAIC) trial [41], oxaliplatin became part of the chemotherapy regimen. Also, irinotecan was demonstrated to improve the effectiveness of 5FU and LV. Hence, the principal protocol of adjuvant therapy was FOLFOX (5FU, LV, and oxaliplatin) or FOLFIRI (5FU, LV, and irinotecan). In addition to this regimen, especially in stage-IV disease or stage III refractory to chemotherapy, targeted therapies (see above) [42] have become the first-line therapy in recent years. They demonstrate a good decrease in median progression-free survival and better quality of life in the absence of mutations of KRAS or BRAF.

Surgical Treatment

Laparoscopic Colectomy (LC)

Laparoscopic surgery for CRC has undergone slow (but tremendous overall) advancement since 1991, when first laparoscopic colonic resection for cancer was described. LC can today be considered the gold standard surgical treatment for colon cancer when indicated appropriately. Randomized clinical trials have shown that this method is safe and effective for malignant disease with oncologic outcomes equivalent to open surgery [43–45]. LC results in a shorter hospital stay as well as less morbidity and postoperative pain than open colorectal surgery.

Nevertheless significant socioeconomic disparities in the use of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for colorectal disease remain. A recent revision of 211,862 colorectal resections carried out at high-volume hospitals in 2008 in the USA [46] demonstrated that only 16,637 (7.3%) colorectal resections were done using MIS. It was found that racial and socioeconomic factors influenced appreciably the access to MIS for CRC treatment. Laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer is the cornerstone of enhanced recovery programs thanks to its lower level of injury to potentially complex, immune-challenged hosts. The underlying philosophy of FT programs is to capitalize upon small differences to effectuate more important global benefits in overall patient recovery in the hope that the short-term advantages of enhanced-recovery colonic surgery may have important cumulative long-term benefits. Clearly, further investigation is warranted. Under the impact of an ever advancing technology, enhancing the ergonomics and extending the boundaries of MIS, the next few years are expected to be very promising for laparoscopic surgery of colon cancer with prospective randomized studies reaching full maturity and having the possibility to extend the follow-up to a more significant period of 10 years. The integration of enhanced-recovery regimens with laparoscopic methods should also provide greater uniformity of clinical outcomes throughout the world. Furthermore, the previously arduous learning curve will predominantly be addressed in the postgraduate training period. The comparisons of experiences will probably lead, in this decade, to an evermore important technical standardization of colectomies.

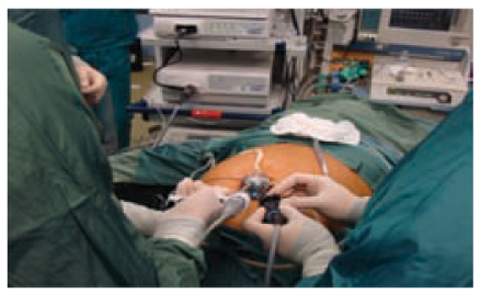

Single-incision Laparoscopic Colectomy (SILC)

Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) represents the latest development in laparoscopic surgery and has been promoted to improve the cosmetic effect and incisional and/or parietal pain as well as to reduce port site-related complications. The initial increases in surgical costs associated with purchasing new equipment do not seem to be mitigated by a significant reduction in morbidity and duration of hospital stay [47]. SILS has several disadvantages compared with multiport laparoscopic surgery with regard to surgical instruments and methods. One of the biggest challenges associated with SILS is the optimal positioning of instruments. Therefore, SILS requires an experienced surgeon to overcome the difficulties of triangulation, pneumoperitoneum leaks, and instrument crowding. In fact, many cases require conversion to open or multiport laparoscopic procedures to get better retraction or aid in colonic mobilization. Some investigators recommend utilizing articulating instruments or variablelength tools, including a bariatric-length bowel grasper or an extra-long laparoscope to minimize external clashing. Most of the experiences in SILC have been in the setting of right hemicolectomy [48] (Fig. 3.1). This is because this procedure was proposed as an intracorporeal ileocolic anastomosis using an Endo stapler and closure of the orifice left from the stapler by the endostitch that requires limited wrist movements to avoid interference with the endoscope. It was also to avoid mesenteric traction occurring with extracorporeal sutures, which often involve enlarging the incision of the multiport device [49]. Further advantages can be gained from the use of particular access ports to allow the introduction of several trocars multiple times, for example using Gelport™, in which trocars can be kept apart for as long as possible to maintain instrument triangulation and to prevent clashing outside the abdomen. It has recently been suggested [50] that the implementation of robotic technology to SILC could help overcome some of the difficulties associated with conventional SILS.