Above-Knee Amputation

Daria Brooks Terrell

BACKGROUND

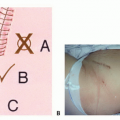

Although many bone and soft tissue sarcomas of the femur and thigh can be treated with limb-sparing techniques, some aggressive tumors are complicated by neurovascular involvement or extensive soft tissue contamination and thus require an above-knee amputation (AKA) (FIG 1).

An AKA is a transfemoral amputation of the lower extremity. AKAs are usually classified by level: high (just below the lesser trochanter), standard or midfemur (diaphyseal), or low distal femur (supracondylar).

In general, transfemoral amputations with 50% to 70% of the residual bone length (measured from the greater trochanter to the lateral femoral condyle) are optimal. However, when amputations are done in an oncologic setting, the amount of femur remaining is determined by the extent of the tumor.

Generally, if 3 to 5 cm of bone distal to the lesser trochanter remains, a standard AKA prosthesis can still be used.

ANATOMY

The surgeon must be familiar with the major neurovascular structures of the thigh because these structures will need to be identified and ligated. The femoral artery is the main artery of the thigh and femur. Its course changes throughout the length of the femur and, therefore, its location varies depending on the level of amputation (FIG 2).

High Above-Knee Amputation

Proximally, the femoral artery lies beneath the sartorius muscle, anterior to the adductor longus muscle, and anterior to the femur. The profunda femoris artery lies posterior to the adductor longus muscle. At this level, the femoral artery is lateral to the femoral vein. The sciatic nerve lies posterior to the adductor magnus and anterior to the long head of the biceps.

Midfemur Above-Knee Amputation

The femoral artery lies between the vastus medialis and the adductor magnus and is medial to the femur in the midthigh area. In this region, the femoral vein is lateral to the artery. The sciatic nerve lies between the short head of the biceps and the semimembranosus.

Supracondylar Above-Knee Amputation

The femoral artery is directly posterior to the femur. After passing the canal of Hunter, the femoral artery joins the sciatic nerve in the popliteal fossa. The artery is deep and medial to the sciatic nerve.

INDICATIONS

Local recurrence of malignant carcinoma or sarcoma where limb salvage would not yield a functional limb or effectively remove the disease (FIG 3A)

Tumors with major vascular involvement with invasion of major blood vessels, which usually have poor outcomes and a poor prognosis (FIG 3B)

Soft tissue contamination, such as after a pathologic fracture

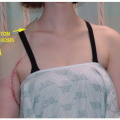

Tumors of the distal lower extremity with major nerve involvement, as with tumors of the popliteal space (FIG 4A,B)

A poorly planned and executed biopsy, which can cause extensive contamination

Infection, particularly in the case of tumor ulceration

Skeletal immaturity, which often leads to significant limb length discrepancies when limb-sparing procedures are done on skeletally immature patients

Extensive tumor involvement that prohibits adequate soft tissue coverage of a prosthesis (FIG 4C-E)

IMAGING AND OTHER STAGING STUDIES

Plain Radiography

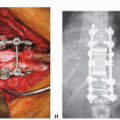

Plain radiographs often provide the first indication for the need for amputation and an initial estimate of the necessary amputation level.

Orthogonal views of the femur, tibia, and fibula can be helpful in showing tumor involvement and the extent of bony destruction, although, generally, up to 30% of the bony architecture has to be destroyed before radiographic findings are apparent (FIG 5A).

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the most helpful in determining the level of intramedullary tumor involvement and the extraosseous extent of the tumor, which is used to determine the amputation level (FIG 5B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree